Whilst the new year typically bears an air of prospect and possibility, almost every university in the UK will experience quite the opposite as we enter 2023. Demanding change, over 70,000 staff across 150 universities are proposing an updated set of new year’s resolutions for their employers: improve staff wages, restore pension benefits, and ameliorate working conditions. Set to be the biggest succession of university strikes in history, here’s everything you need to know about the upcoming industrial action…

What:

Aiming for progress, university staff will paradoxically halt many academic and administrative operations over 18 days of strike action, interrupting lectures, seminars and marking processes.

When:

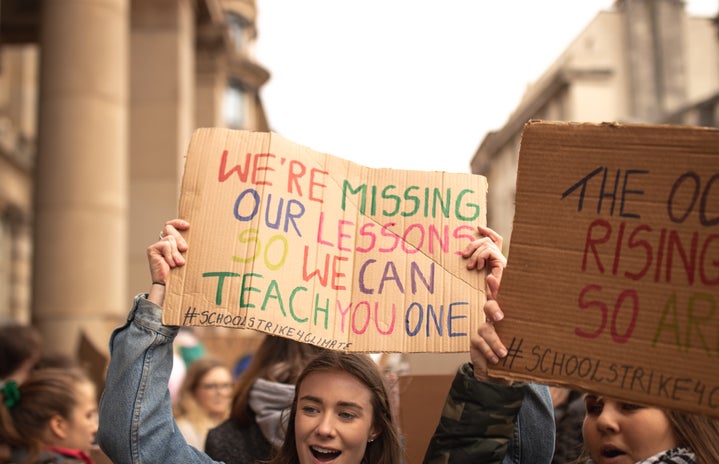

Commencing on Wednesday 1st February, the first day of university strikes effectively coincided with the Trades Union Congress ‘protect the right to strike day’, in which the University and College Union (UCU) protested with train drivers, teachers and civil servants against the Conservative government’s anti-strike legislations. Reverberating Margaret Thatcher’s anti-union regulations that sought to curb power and limit potential for strike action, Rishi Sunak aims to impose laws ensuring that workers will lose their jobs if they vote to strike.

Subsequently, members of the UCU will strike on the following days:

- 1 February

- 14, 15 and 16 February

- 21, 22 and 23 February

- 27 and 28 February

- 1 and 2 March

- 16 and 17 March

- 20, 21 and 22 March

Establishing these petitions over a decade ago, staff are persisting to battle for equity until meaningful developments are achieved. Having gained traction over the years, the UCU are prepared to utilise their influence and re-ballot members of staff at every UK university until their demands are met. Strike action could therefore prevail well into 2023, with an agenda to even impose a marking boycott in April.

Why:

The country is currently surviving a cost-of-living crisis, so it’s naive to think that university staff are immune to these struggles, especially since their employers have significantly hindered their ability to cope. In response to the brief strike action this academic year in November, the Universities and Colleges Employers Association (UCEA) offered an embarrassingly inadequate pay rise of only 3%. To contextualise this, this is ridiculously below the rate of inflation, which currently stands at 14%. Although recently proposing to increase this to 4-5%, staff have rejected UCEA’s offer, asserting that it is clearly not enough.

Pension cuts made in previous years only exacerbate these circumstances. On average, staff saw losses of 35% from their retirement funding last year, provoking an appeal for employers to revoke benefit cuts.

Who:

Amidst the disorder, it’s easy to lose sight of who is most affected by these strikes – students. Catalysing debate and confusion, students often hold conflicting opinions on industrial action. It’s easy to assume a stance of frustration, castigating staff for lazily refusing to work and repeatedly asking, ‘well, where is my 9 grand going?’. However, it’s important to remember that our lecturers are not acting against us, but rather, for us.

Not only have the UCU persistently advocated for the abolition of tuition fees, but they also work highly skilled and demanding jobs to provide us with an education, tackling an excessive workload that results in hours of unpaid work. Diminishing the impact on students, staff further endeavour to extend deadlines and reschedule teaching. Now, although this won’t change the fact that students are left without compensation, without guidance and without clarity, the university should not be held accountable.

With the government turning a blind eye to staff pleas and refusing to refund students for lost time at university, ask yourself this: who is really to blame here?