Immigration is an issue that is discussed at length in the world of politicians. We as a country continue to wrestle with it. And for most of us, it would be the last thing to consider amongst Black Lives Matter, Women’s Rights, Climate Change, Abortion Rights, etc. But for some of us, it is a haunting shadow touching every second of our lives.

Since the late 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, we have seen a steady rise in immigration. Throughout much of the twentieth century, it was the migration of European families into the United States. This majority shifted to the migration of Asians and Latinos in the 2000s. And for that, the economy is the culprit.

There is something about the promise of opportunity that directs people here.

For my family, it means quality education and not having to live paycheck to paycheck. Although my parents were well-educated people, they struggled to find jobs with consistent paychecks and sometimes juggled multiple jobs in a year. It was only after finding a stable (but stagnant) job that my parents received an opportunity to work in the United States. They prayed that their children won’t have to follow their struggles despite having the privilege of education. You can say this sounds like the common “immigration story” many people hear about.

Many immigrants bring their families to the United States. For these immigrants working on temporary visas, there isn’t a clear path to legal permanent residency. Many immigrants apply for legal permanent residency (A.K.A the “Green Card”) through their employers. Unfortunately, there are long waiting lines and only so many Green Cards that can be offered to each country each year. For countries with a large population applying for the Green Card, it can take a longer time to receive one. Moreover, with constant backlogs, shifts of policies based on political powers, and country allocations, you can end up waiting in line for the next 40 years. And this isn’t even citizenship.

When these immigrants come to the United States and bring their children, usually around 5-8 years old, the children are in a dilemma. The children can only stay as minors and retain their lawful dependency status under their parents’ visas until they turn 21 years-old. After they turn 21, they “Age-out” of that status.

For those young people who turn 21 and can no longer retain immigration status, they have to self-deport to a country that is only wisps of memories.

And that would be my story. I have resided in Texas for the past 12-13 years and went through similar experiences that most of us have. Taken part in sports, staying late for afterschool fine arts, and grumbled about Mr. so-&-so giving too much homework. It wasn’t until my junior year that that my immigration status becoming a barrier. I wanted to have summer job to support my family, but my visa barred me from work authorization.

And I thought, “Alright, it’s ok.”

As I went through senior year, I found that I cannot apply for a majority of the scholarship despite excelling in academic and extracurricular activities because I’m not a permanent resident nor a citizen. Soon, I realized that I cannot even apply or receive most financial aid, so my parents will have to pay my entire college tuition. The only thing that “saved” me is the in-state tuition that I pay as a Texas resident.

But for the first time in college, I found that I cannot get most internships because I don’t have work authorization. It wouldn’t matter how many career fairs I attend, how much time I spend building my resume, or how many connections I make, if I can’t have the opportunity to work.

Ironically finding a job or an employer is the way for me retain to my legal immigrant status after turning 21. It would be my way to prevent deportation.

And that when it hits me “Maybe, it’s not ok.”

It would only end up as a tragic play if it was my story alone. However, this story is tiny window to the world of more than 200,000 young people living in the United States today. With no legislative currently protecting them from their deportation, these young people with uncertain futures call themselves “Documented Dreamers.”

Because the Documented Dreamers have a lawful status when immigrating to the United States, they are excluded from the protection of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). DACA has only aimed to protect children who came to the United States illegally from deportation. President Barack Obama approved this decision in June 15, 2012. However, one can say this is a temporary band-aid to the situation.

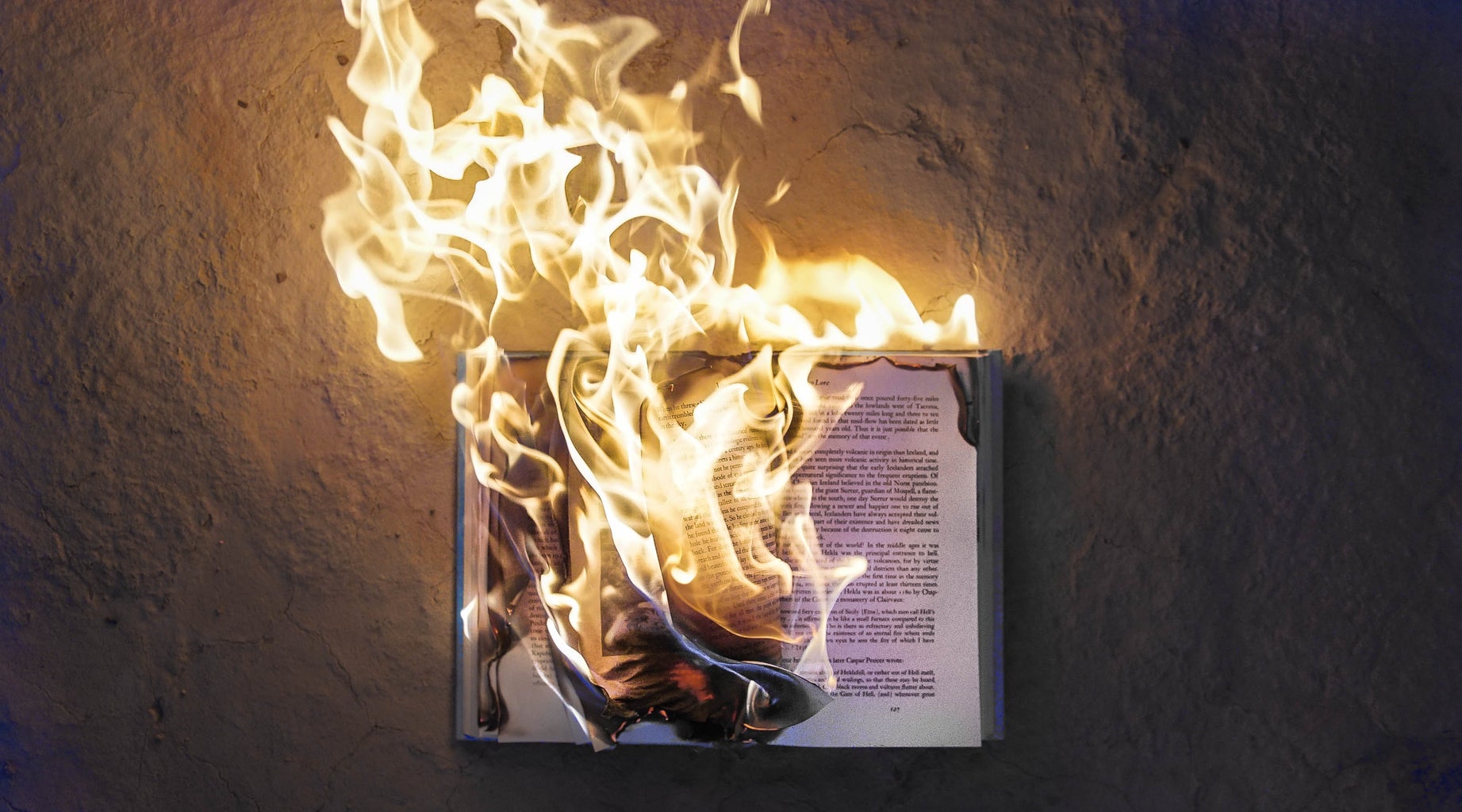

There has been many attempts to remove the “aging out” barrier on the young people who came to United State as young children. In fact, the Dream Act to protect these children has been introduced in Congress 11 different times (even in 2021) and was continuously revised over the past two decades. However, it would fall short of a few votes, barely missing the opportunity to become a law. And for people like me, sometimes all we can do is wonder…

“Will there ever be a day where immigration children won’t have fear deportation? Will we ever be able to dream of the ‘what-if’?”

And from a dreamer who wants to dream, I just want to say,

“We are human beings, too.”