PEN America, a nonprofit dedicated to raising awareness of the diminishing freedom of speech in libraries and classrooms throughout the United States of America, recently reported that during the 2023-2024 academic year, there were 10,000 instances of books banned.

In its Index of School Book Bans, PEN America states that among the most widely-banned books are titles such as Black Reconstruction in America by W.E.B. DuBois, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, and 1984 by George Orwell — I am sure this irony is lost on many who oppose its presence both within the classroom and in the evolving minds of young adults.

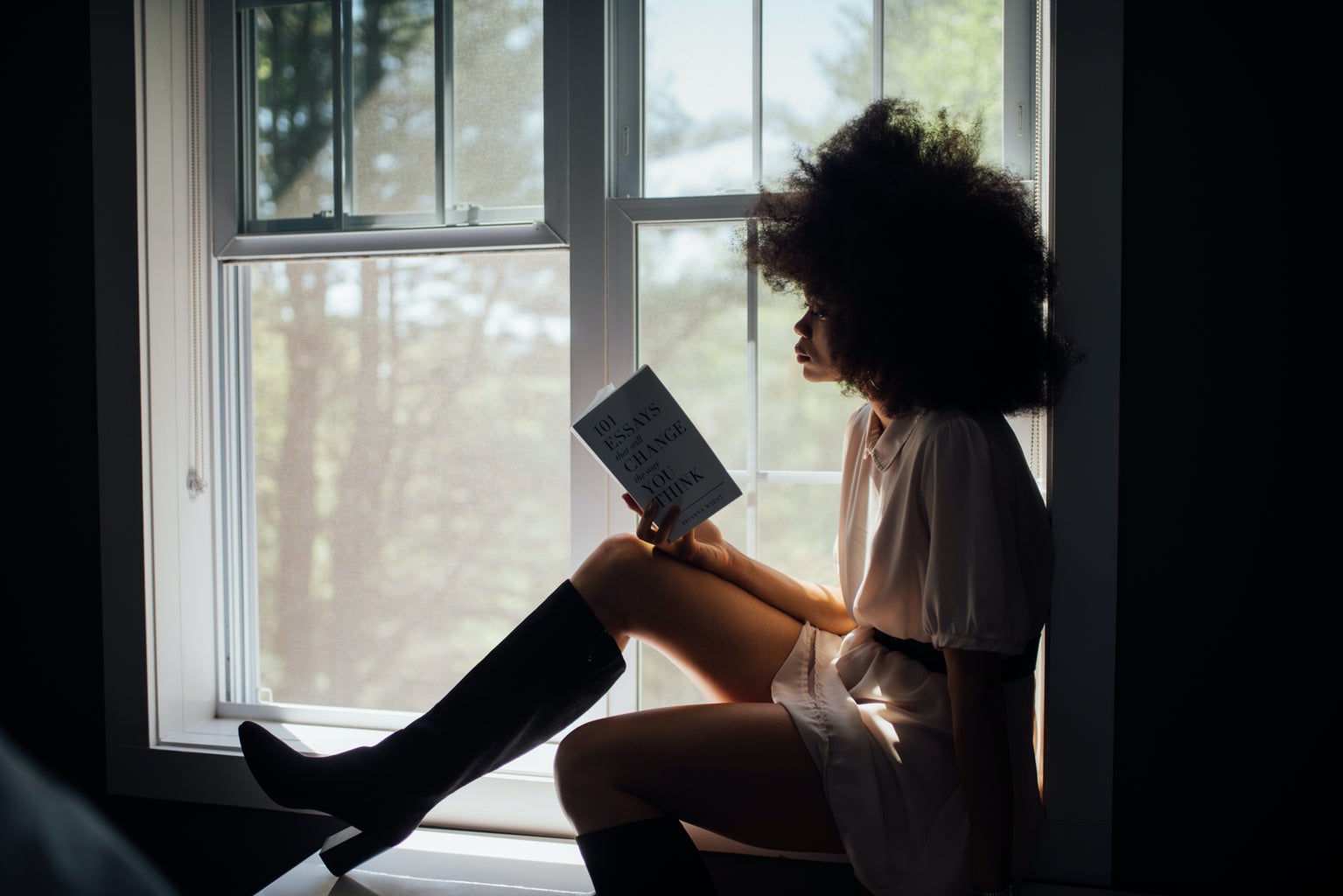

I am ashamed to admit that I have yet to check each and every book off of my To-Be-Read list. In fact, I have read less than 20% of the titles listed, a mere 19 of them. However, I found that within this collection lie some of the most heart-wrenching and fundamental texts of my literary upbringing, including but not limited to Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak, and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic.

In my preteen and teen years, I devoured every dystopian novel I could find on the shelves of the public libraries I frequented. Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games (which made an appearance in the American Library Association’s list of the Top 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books from 2010-2019) and Veronica Roth’s Divergent were my bread and butter. At 12, I did not feel as though I had the ability to change the world through radical social movement. I did not feel as though I could stand arm-in-arm with my fellow pre-teens and eradicate prejudice.

Yet, as I trudge through my 21st year, I understand why The Hunger Games is being banned from public school systems and public libraries, aside from the idea of graphic or gore-y scenes; these dystopian novels encourage public pushback to the social norms running rampant in society. There is fear on the part of those proposing these bans that by reading these books, children will become more politically aware and vocal about injustice in their communities.

The banning of books is a problem — an epistemic one. By limiting the texts and messages that children and young adults are exposed to, the institutions including the nuclear family, school, the workplace, etc. will continue to control the behaviors and ideals of the public. Isn’t this terrifying?

Now, I wholeheartedly believe that there is something to be said for the innate capacities of human beings to empathize with one another, but I also believe that there is an educational element to this. Ideally, we should be able to feel for our fellow human beings and stand up for one another without necessarily experiencing what they are going through. However — and I do not think I am completely out of line by saying this — somehow American (and global) society has flown so far off the handle that these textual retellings and explorations of human experiences are now deeply vital to the empathetic upbringing of youths.

It is a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad predicament, and one that stems from the desire to squash narratives against a “woke” agenda, therefore breeding a culture of overflowing hatred that is void of empathy. It is a threat. It is a greater threat than letting your 14-year-old daughter read Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games.

We need to read banned books and support the authors who write them, because these bannings show that the marginalized identities which these texts are primarily centered on are under-represented and under attack.

History has shown that this is a routine act, and one that repeats itself. Censorship has been used as a weapon for centuries — from the McCarthyism censorship of “communist” materials and the subsequent fear mongering that came from this to the banning of menstrual product advertisements on public television until 1972. Censorship and bans constitute the textbook definition of oppression, and we need to make sure the curtains close on this cycle.

By purchasing these texts, signing petitions, and protesting the banning of literature, we will be doing our part in stopping this epidemic of hatred and suppression of empathy.