Although only occurring five times in total throughout US election history, there have been instances of presidential winners dominating the Electoral College, yet failing to win the popular vote. Recently, however, this phenomenon has picked up momentum as two out of the four most recent presidential elections have followed suit, calling the legitimacy of the current system into question. Before expanding on the problems with the college, here’s a brief crash course on how the Electoral College works:

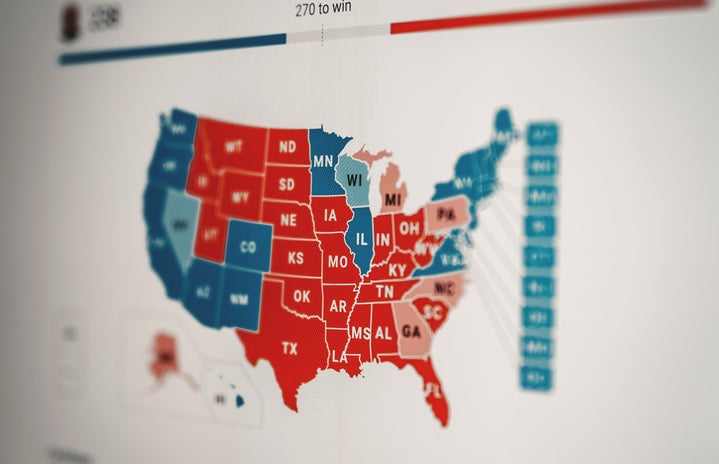

There are overall 538 electors, a summation symbolizing the 435 national representatives and 100 senators, whilst allocating three for Washington DC as well. Each state automatically receives two senators, but the amount of representatives for each state is reapproportioned every 10 years after a national census, which tracks state populations. In order to win, a candidate must procure at least 270 of these votes.

Both candidates possess a group of electors from each state, known as a “slate.” While selection laws vary by state, the electors are typically chosen either via nominations at the respective party convention or a vote of the party’s central committee, on account of their party loyalty. The Constitution provides little provisions surrounding this, but some limitations are that no person holding a national-level office or past participation in an insurrection can be in contention.

During the general election, when someone votes for a candidate, it’s counted towards a state tally with the slate whose candidate accumulates the most winning the opportunity to participate in the post-general election vote over the other party’s slate. A Certificate of Ascertainment is consequently created by each state executive, listing the chosen slate members. The election that finalizes who wins the presidency doesn’t happen until the first Tuesday after the second Wednesday in December. Only a projected winner is announced on general election night.

Meetings are then held for the electors in each state to formally cast their votes for the President and Vice President on separate ballots, which are then recorded on a Certificate of Vote before being sent to Congress to be counted by House and Senate members on the subsequent January 6th. At the end, the President of the Senate announces whom and if there is a winner.

Whilst only becoming increasingly complicated over the centuries, the conception of the Electoral College was a compromise between a vote in Congress and a forward popular vote. The idea persisted as the best option because of the perceived protection weighted votes would guarantee for less populated states, except that there’s no concrete evidence of such. In the modern era, people from sparsely populated states tend to be Republican, while Democrats reside in densely populated ones. This creates an overrepresentation of Republicans and a demand for a system more in line with equity principles.

It’s theorized that the process remains the same because the incumbent party benefits from its existence and the minority party possesses little power to enact change. Despite the advantages for politicians, the Electoral College continues to be the less than effective democratic method for a multitude of reasons.

One is the arbitrary compartmentalization of the American people based on geographic location into states. The battleground state phenomenon has thus resulted in candidates focusing their campaigns more on the residents of battleground states due to the advancements in political polling- leaving little attention for the rest.

In addition, the state governments across the country will and often have gerrymandered their congressional districts. Meaning they’ve designed them intending to underrepresent marginalized groups of people during national elections with attempts to ensure a certain percentage of the population are members of their party.

Nothing in the Constitution requires using this process, exemplified by Maine and Nebraska employing the congressional district method. This system allocates one electoral vote to each district with the statewide vote’s winner obtaining the extra two votes, instead of simply all the electoral votes going solely to the statewide winner. But this strategy is susceptible to the winner winning the Electoral College, but not the popular vote. This is due to (1) how Republican support is more evenly dispersed amongst districts and (2) its retention of the unit rule, in which minority votes are not recognized.

The alternative favored by many political analysts and 65% of the general population according to a 2023 Pew Research poll is the national popular vote plan; a plan that proposes all Electoral College votes would be awarded to the candidate with the most popular votes. Currently, 15 states and Washington DC have passed legislation to enter the national popular vote interstate compact, comprising 196 electoral votes or 72.6% of the Electoral College.

It’s predicted that this plan would not only reduce Americans feeling as though their vote isn’t worth much in the grand scheme but also actually represent individuals’ votes more fairly. This would also mitigate accusations of electoral fraud and presidential illegitimacy as seen with the past 5 administrations.