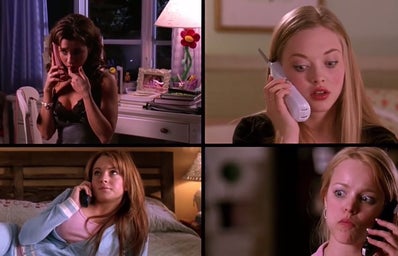

The villain of the 2004 cult classic Mean Girls remains an icon of silver-screen history. Her evil genius gives full force to the movie’s title, as we see her sabotage those who surround her with seemingly merciless tenacity. Among her extensive crimes is the creation of the infamous ‘Burn Book’, essentially an anthology of insults about the female students at North Shore High. From The Princess Diaries’ Lana Thomas, to ‘slaggy’ Lindsay in Angus Thongs and Perfect Snogging, this Queen-Bee type bitchy high school character has become a cliché of teen cinema. And yet, to what extent is there something problematic about this familiar figure, and for what reasons might such characterisations be better left in the past?

First of all, it is interesting to consider whether these personalities really exist. While some might have been unfortunate enough to have come to blows with such vindictiveness, I genuinely attest to have never encountered anything so extreme. Regina is perhaps instead an amalgamation of more general high-school bitchiness, of which many are guilty. The film is based on a non-fiction book by Rosalind Wiseman, Queen Bees and Wannabees, which aimed to help young girls cope with high-school cliques and aggressive behaviour. The self-help book was a New York Times Bestseller, reiterating a demand in the market.

Yet, we cannot ignore the fact that these characters’ motivations are invariably directed at getting the attention of some unassuming and oblivious ‘hottie’ like Aaron Samuels. Regina is scheming, cheating and promiscuous, all to the blind eye of her boyfriend, upon whom it would be difficult to cast a single strand of moral judgment over the entire film. Aaron is a peripheral figure, used primarily to motivate the duelling teens. Whereas male protagonists typically fight over wealth and action-driven plotlines, female characters pine over popularity and boys.

Despite all of this, Mean Girls is undeniably a work of cinematic art, and it is not for its docile ‘heroine’ Cady Heron that it remains so popular. Instead, all eyes turn to its chief antagonist Regina, whose Machiavellian philosophy cannot go unappreciated, we admire her cunning. There is also reconciliation at the end of the film as Cady gives out a speech celebrating her female comrades, rather than a Cruel Intentions-style Deus Ex Machina which sees the high school bully publicly humiliated (although it remains a personal favourite.) In this sense, the plot avoids the tendency to end with ‘good’ triumphing over ‘evil’, instead offering a more complex finale.

Overall, while there is something slightly weary about this stereotype, a film so undeniably well-written and produced as Mean Girls is difficult to cast aside. Although the over-saturation of such airheaded female characters might pose questions as to the representation of women in cinema, we can still venerate the movie as an absolute classic, which should not fall victim to cancel culture’s venomous bite. Rachel McAdams’ portrayal is full of wit and originality, without falling into the tropes of the token bitchy blonde. She is more than just Cady’s evil double, commanding the film with her savage language and genius charm. Execution, it seems, makes all the difference.