Edited by: Malavika Suresh

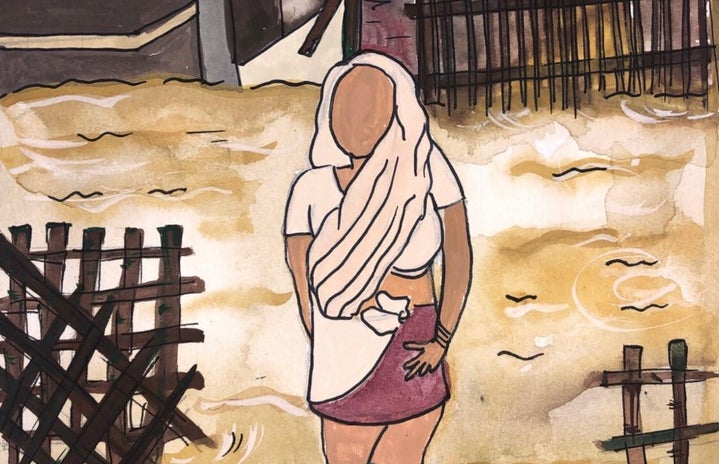

In the flood-affected zone of Muzaffarpur, Bihar is a historically neglected Dalit village Karhattiya, where three women live: Fulmatia Baitha, Sulochni Pasi and Jagdamba Paswan. They live in the Beentoli (community of weavers) and are often depicted as ‘empowered’ women from rural areas as they are a part of the labour force. However, the experiences of these women are far from it. These women are exploited daily and paid much less than their male counterparts. They are oppressed socially and financially. This stark reality can be witnessed during the floods in Bihar. While the physical effect of floods is the same on all, vulnerability and harm vary with social position, caste, and gender. Women – especially those belonging to this marginalized community – are exploited mentally, physically, and financially.

These women did not lead a good life before the floods, but the floods in Bihar, India’s most flood-prone state, have worsened their situation exponentially. Rivers have always been the source of prosperity and fertility. Water has always been synonymous with life. But in Bihar, these rivers are simultaneously equated with Maai (Mother) and Dayan (Witch). Biharis celebrate Chhath Pooja in these very water bodies and have to deal with its wrath later. While the government has made embankments, a report by Dr. Dinesh Kumar Mishra of the Barh Mukti Abhiyan, an NGO which works on the flood control policy of Bihar, says that the floods and its effects have more than doubled. The embankments, which have increased waterlogging, have created vast marshlands and have made the water unfit for use. People own lands between these embankments and their cattle live on these lands. Unfortunately, the lands are very prone to soil erosion, turning them into heaps of sand. The extreme impact of this situation can be better understood from the perspective of the women who live there.

Fulmatia is the primary earner of her household as her husband works as a labourer in Delhi. Due to this, she has to be the ‘man’ of the house – she must perform duties conventionally said to be the role of men in a village household – while maintaining her feminine identity and dealing with the oppression attached to it. The struggles faced by Fultmatia do not end with her. Fulmatia’s young daughter has to focus on household chores when her mother goes out to earn their daily bread. During the floods, Fulmatia’s daughter, and many like her, have had to drop out of school. Sadly, their access to education or, the lack thereof, is the least of their concerns. When the floods come, not only is Fulmatia’s livelihood lost, but she also has to take care of the elderly and the children of the family who may get sick because the water body from which they get their water becomes contaminated. After the floods and the resulting destruction, they are also forced to live in temporary settlements such as tents and shelter houses which lack clean water supplies and proper toilets. Not to mention, women like Fulmatia and her daughter are worse affected due to their vulnerability to diseases and infection resulting from a lack of hygiene resources to cope with menstruation.

Another experience comes from Sulochni, a new mother during the floods. She had given birth to a baby boy, but could not feed him because she was severely malnourished. Women used to work in the fields, but as the floods submerged them, they lost farming as a source of income. Unlike their male counterparts, they cannot go outside to earn money through labour and other non-agricultural jobs to take care of their families. Lack of resources and information means that people like Sulochni are unaware of relief funds, government aid, and shelters. Due to this, she is unable to access necessities that affect not only her health and well-being but her newborn as well.

Jagdamba, named after the goddess, does not believe that Devi Jagdamba is on her side. She believes that she is being punished for the crimes of her past life. Due to the caste system that continues to prevail, another of the damaging aspects of the struggle of these women is that they have been led to believe that they deserve what they’re dealing with, simply because of their place in the caste hierarchy. This idea of being cursed and the floods as a way to punish them by the Gods is deeply ingrained in Jagadamba. She believes these struggles are natural and she refuses to believe otherwise. She refuses to believe that she could someday have a good life – that maybe her kids could have a good life. The floods may be natural, but the destruction caused by these floods isn’t and is due to poor public policies and government negligence.

However, these women do not sit down and let it pass. They have devised creative strategies for coping with and recovering from these floods. These weavers have weaved their lives around these floods. They have weaved baskets out of the bamboo that grows around the water bodies. Additionally, they make jute out of the Patsan which grows in these waterlogged areas. They cannot overlook/ignore the floods, they can’t look for a vaccine because there is none, what they can do is learn to live with them, cope with them, and hopefully conquer them someday.

While they attempt to cope, the solutions to these disastrous floods are complicated – disaster management protocols have been so ineffective that communities have had to rely on themselves. During relief distribution, women are excluded from the process but have now taken matters into their own hands. It is not that they don’t want to take help from the government, but they are unable to because the government has been ineffective in running their distribution channels. Women have had to use their indigenous technical knowledge to come up with solutions. The lack of government officials on the ground has resulted in the failure to protect embankments, run proper relief camps, and provide clean water. People have to gather their broken lives by themselves, but they believe that they can get there.