Content warning: sexual abuse, sexual trauma

My closet is filled with dresses, which I once loved to wear, but are currently desperately neglected. As a child, my mother used to help me shop for traditionally feminine dresses and outfits: frills, flowers, and skirts all complete with a nauseating pastel palette to complete the look. Mistaking my complacency for my stereotypically feminine childhood wardrobe for actual adoration for the frilly fabric ultimately contributed to my teenage crisis about my fashion sense and existential identity.

The style of my youth later helped me realize that I felt awkward in flowing drapery and pink patterns. Growing into my teenage years, I thought it might be a bit redundant to be an awkward teenager who felt unbearably out-of-place in her own clothing, so I experimented a bit with my style identity.

My overwhelming attire awkwardness led me to overcompensate my previously floral designs and ruffle hemlines with the onyx and black color schemes that could only be found at Hot Topic and a vampire’s dwelling. The brightest outfit I donned during my clichéd teenage goth phase—which ultimately transitions into a more refined, but divergent goth style later in my life—was when I channeled my inner Michael Keaton in complementing black and white stripes (because Wednesday Adams might be synonymous with goth fashion, but Beetlejuice is an underappreciated, but well-deserved, goth icon).

Even in my obsidian gowns, skull accessories and baggy black jeans, I still felt far away from comfort— until I donned my first business professional cohort for an internship interview.

It might save precious article space to say that my transition from my grungy goth apparel miraculously happened once I put on a perfectly tailored trouser-suit and I felt infinitely feminine in my own version of feminine fashion —but that wasn’t necessarily the case.

After the interview, I took off my blazer and matching pants, and I forgot about how confident and fashionable the outfit made me feel—because I just assumed that my confidence was from my pre-interview preparation, not my attire. But, I found out that I got the internship —which meant I needed to rotate my less-than-office friendly t-shirts and Morticia Adams gowns with my growing collection of pencil skirts and button-up blouses.

It wasn’t until after I was sexually abused and raped that I began to realize how pantsuits made me feel incredibly feminine. Following my trauma, I naturally felt isolated by my own body and actively wore loose-fitting, modest clothes to hide my figure and my skin. Because the person who sexually abused me violated my body, my body itself made me feel simultaneously more vulnerable, damaged and unsexy. Feeling betrayed by my body prompted me to wear more masculine clothes so that my body couldn’t indirectly make me susceptible to future abuse again—even if it wasn’t my body’s fault, nor was it my own.

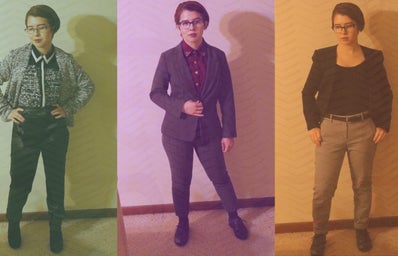

Because I still needed professional outfits, I turned to what I thought was the most masculine ensemble ever: the pantsuit.

Wearing all sorts of pantsuits initially allowed me to regain stability in my life following my sexual trauma, as I was able to rely on the security that the long suit jackets would cover my arms and the pant legs would hide my lower half. The pantsuits concealed my body, which made me feel safe.

As my pantsuit collection gradually accumulated, so did my appreciation for pantsuits; however, my opinion toward the closet staple also started to change. Though I used to think pantsuits were inherently masculine, because men typically wear them as opposed to women, I noticed that my suits allowed me to start to accept my body again and allowed me to look at my internalized gender norms more critically.

Albeit a good amount of therapy also attributed to my rediscovered body-positivity, pantsuits made me realize that I don’t need to wear traditionally feminine attire to look, feel and be feminine. Although I began to wear pantsuits as a coping mechanism, pantsuits become a way for me to become and feel like a perpetually powerful woman, simply because suits are particularly synonymous with power in the professional world.

My suits helped me recognize that, like the rest of my identity, my femininity is multifaceted. Similar to the women in the early 1900’s who protested gendered clothing and were subsequently arrested for wearing pants, I could find my own version of feminine empowerment in pants—specifically pantsuits.

While I’m not at risk of being arrested for wearing a pantsuit, pantsuits allow me to express my femininity without the insistent pressure of toxically feminine-gendered clothing like skirts and dresses.

Gendered clothes often make women, as well as men and non-binary people, feel pressured into dressing a certain way. When an entire department of women’s clothing is mostly filled with dresses and skirts, even for professional wear, this pressure becomes insurmountable to avoid. Even wearable guides for pantsuits alone seem to pressure women into transforming a typically masculine-structure suit into something more delicate and dainty. However, femininity is more than looking and feeling delicate; femininity itself is about feeling powerful and intense.

Whittling down femininity into floral designs and dresses ignores the fact that being feminine isn’t just about having a soft aesthetic. Just like flowers and floral designs shouldn’t innately be considered feminine, flowers themselves are often overtly powerful. For instance, the bleeding heart flower is so potently poisonous it can cause skin irritations even in humans.

Sequestering certain fashion designs, such as flowers, or styles of suits or other outfits to a single-gendered section is a bit narrow-minded. In fashion especially, delicate designs and powerful wardrobes should be interconnected so that femininity and power can be instinctively intertwined. Mixing and matching my pantsuits allowed me to not only recover from my trauma, but also deconstruct what I previously thought to be feminine fashion and mold my own definition of what it means to be feminine.

In my specific case, it took a traumatic instance to rediscover my fashion identity and inevitably realize how impractically uncomfortable pencil skirts are (seriously, nobody can walk in a skirt that cinches are your knees and nobody wants to waddle in a skirt that makes them borderline immobile). What started as a coping mechanism to hide my body and my skin from myself and the world evolved into my new appreciation of what it means to be feminine, especially within the fashion realm. In wearing pantsuits, I’ve also found a reviving sense of appreciation for traditionally feminine fashion fixes likes the dresses I used to hate to wear—and the same dresses that once reminded me of my trauma.