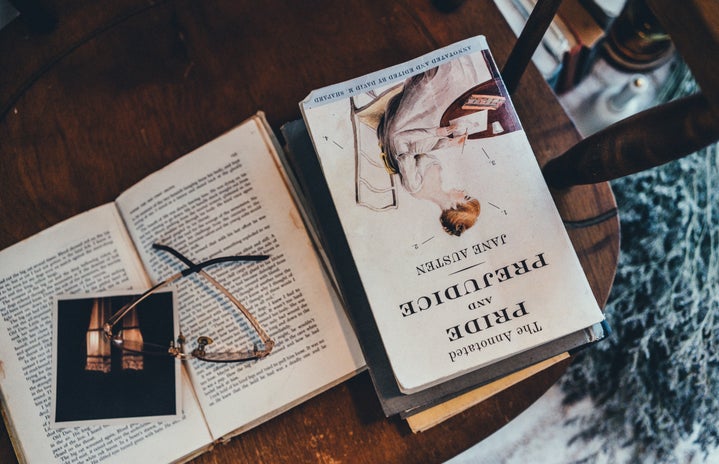

A study published in the Journal of Popular Culture questions the role the queer community plays in regency romance, more specifically, in Jane Austen adaptations.

Regency romance is romance fiction set in the late 18th, early 19th century United Kingdom. In the past year, according to a BBC article, regency romance in popular culture has skyrocketed causing an increase in Jane Austen consumption.

A recent article from the Washington Post additionally suggests that following quarantine, people have wanted more certainty in their relationships. Regency romance provides this certainty. The consumption of television shows such as “Bridgerton” further reflect the growing interest in 18th century relationships.

To determine how Jane Austen adaptations involve the queer community while staying true to the theme of 18th century regency romance, the researcher, Olivia Murphy analyses novels, movies, and television shows from 1996 to the present day.

Olivia Murphy is an English research fellow from the University of Sydney.

Her study published in the Journal of Popular Culture finds that while many queer Jane Austen adaptations involve similar themes of marriage, shame and secrecy, the adaptations incorporate the LGBTQ+ community in unique ways.

Murphy determines that film and novel writers begin writing their queer adaptations with the hope to maintain the themes of 18th century marriage.

Murphy comments on the well-liked, popular 1996 movie “Clueless” which is an adaptation of Jane Austen’s “Emma:” “In Clueless, heroine Cher Horowitz’s attempt to seduce Christian, the analogue of Emma’s Frank Churchill, signals her ‘cluelessness.’ While Frank Churchill is secretly engaged, Christian is secretly gay.”

However, unlike more recent adaptations, Clueless is characterized as homophobic.

Murphy clarifies, “Christian is eventually outed by Cher’s (heterosexual) friend Murray in a rhetorical explosion of erstwhile euphemisms: ‘Your man Christian is a cake boy… a disco-dancing, Oscar Wilde-reading, Streisand ticket-holding friend of Dorothy.’”

Similarly, the movie “Bridget Jones’s Diary” explicitly mimics the gay character, Daniel Cleaver.

“Bridget Jones’s Diary similarly employs hints of queerness to comically indicate the unwholesomeness of Bridget’s first love interest, Daniel Cleaver (the film’s answer to Pride and Prejudice’s George Wickham),” Murphy said.

More recent novel adaptations such as 2015 novel “Promises and Petticoats” by Penelope Friday and 2018 “Perfect Day” by Sally Malcolm have moved towards more inclusive messages.

“The prospect of same-sex marriage here is one of reinscription into the broader social narrative of romantic success and personal growth,” Murphy concludes.

Essentially, Murphy finds that the more recent Jane Austen LGBTQ+ adaptations, such as the two most recently mentioned, are advocating for marriage equality. But, at the same time, they are attempting to maintain the regency romance ideal of marriage.

Even in novels such as “Longbourn” by Jo Baker, which deviates further from the original Jane Austen plot by focusing on different characters, the ideal of marriage remains at the forefront of the book.

“In Jo Baker’s Longbourn (2013) on the other hand, a novel that retells Pride and Prejudice from the perspective of the Bennet family’s servants, the elderly butler (given the name Mr. Hill in Baker’s novel, but not in Austen’s) is in a caring marriage of convenience with the housekeeper.” Murphy said. “When he falls ill, she nurses him and summons his much younger male lover to come and comfort the frail old man.”

In novels such as these, Olivia Murphy concludes that “Longbourn resembles most queer families prior to the movement for marriage equality.”

However, the political commentary offered by “Longbourn” strays from a majority of queer Jane Austen adaptations.

“Austen’s plots are not attempting to revolutionize our understanding of what human relationships might look like, or might become, but merely to endorse this eighteenth-century ideal,” Murphy said.

As regency romance popularity and acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community grows, the analysis suggests that future Jane Austen adaptations involving queer characters will more effectively work towards the 18th century ideal of marriage, politely incorporating “a place within this ideal for queer lives and queer families.”