Content warning: This story includes discussion of gun violence and mass shootings. David Hogg is having a busy week. “Last Thursday and Friday, I had to travel to Dallas to speak at a convention of youth activists. I came back, I was a college student for a short time on the weekend, [and] played beer pong with my friends,” the Harvard senior tells me. “Then I went out on Monday to Michigan State University with our staff and worked with some of the student survivors on the ground there. Now I’m back at school, and I leave on Friday to go to D.C. for another meeting.” He claims his schedule only gets this packed a couple times per year, but his planner is filled almost cover to cover despite him only buying it in November.

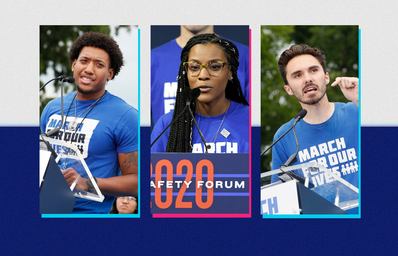

Hogg, co-founder and board member of March for Our Lives, isn’t the only busy one. Director of policy Zeenat Yahya, national coordinator Serena Rodrigues, national organizer Ezri Tyler, program coordinator Ariel Hobbs, and board member Trevon Bosley are also between other commitments when they sit down on Zoom with me earlier in February. Tyler joins from her dorm at Vanderbilt University, colorful posters filling the wall behind her. Yahya apologizes mid-answer for the loud Slack notifications that keep interrupting her. Still, neither the long week, nor the long five years since March for Our Lives was born, seem to have deterred them from their mission.

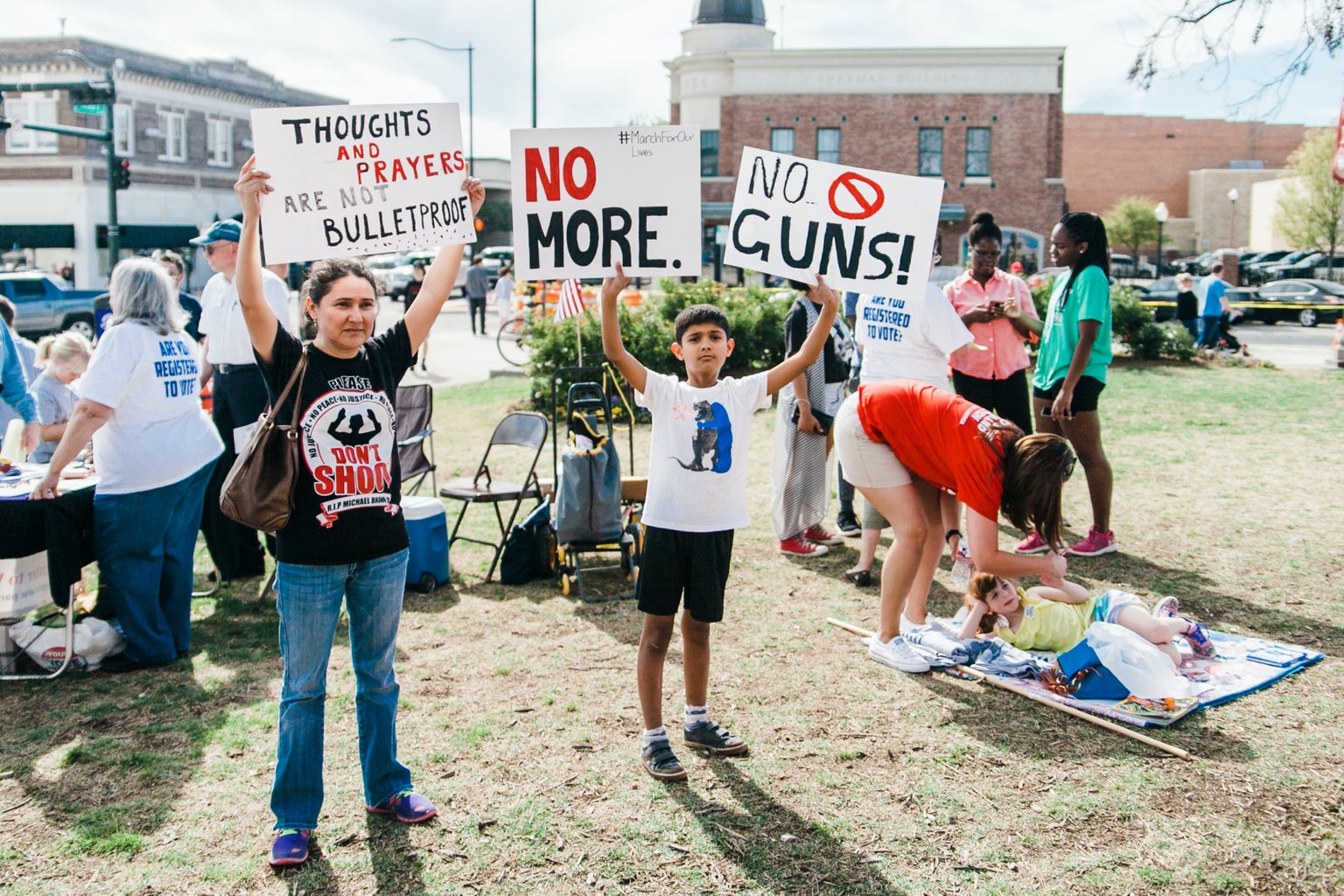

On March 24, 2018, an estimated 1.4 to 2.2 million people gathered in Washington, D.C. to protest the epidemic of gun violence in the United States. The idea for the march came from the survivors of the Feb. 14 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida — including Hogg — who called the movement the March for Our Lives.

The teenagers who founded the movement became household names: They appeared on The Ellen Degeneres Show; celebrities like the Clooneys and Oprah Winfrey donated $500,000 to the cause; you probably remember X González’s impassioned speech at the march that went viral — it was even sampled in a Madonna song. “The marches serve a number of purposes, but I think one of the most important is that we offer solidarity between survivors and show them that they physically are not alone,” Hogg says. The marches are “like a massive form of group therapy for society as a whole.”

But the organizers of the D.C. march, as well as its over 800 sister marches worldwide, were always looking past that initial burst of individual fame. They wanted to start a collective movement that focused on ending all gun violence no matter how long it took them — even as public interest waned. “People with power in Hollywood, in D.C. and elsewhere … I need them to care when this isn’t in the news as well,” Hogg says, pointing to the need for annual sustainable funding. “We need to turn this movement from one that is reactive into one that is proactive.”

The name of the march was very literal. Even in 2023, gun violence continues to be a life-or-death issue, especially for young Americans. According to data obtained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, gun violence has been the leading cause of death for American youth since 2020. In 2023 alone, the Gun Violence Archive reports that over 7,000 people (over 250 of which were 12 to 17 years old) have died from gun violence so far, and 95 mass shootings have occurred less than three months into the year. The United States’ gun epidemic continues to get worse — on June 11, 2022, March for Our Lives gathered over 70,000 protestors for a second march after a shooting in Uvalde, Texas killed 19 elementary school students and two teachers. On Feb. 13, 2023, a mass shooting at Michigan State University killed three students and injured five. “People call [Gen Z] the school lockdown generation,” Yahya says. “It’s not really a matter of if you become a victim of gun violence. It’s becoming when.”

The organizers are determined to change that, and they’ve made progress. “I feel … hopeful [about] our people-powered wins,” Rodrigues says. “On a whim in, like, 48 hours, we were able to get 10 students up to Tallahassee [on Feb. 7] to testify against permitless carry” — the pro-Second Amendment bill that has ignited fierce debate in Florida.

That “people power” has given March for Our Lives a chance to make waves on the national stage, too. In November 2022, Maxwell Frost (D-FL), former national organizing director at the organization, became the first Gen Z representative in Congress. His appointment “made me feel hopeful for the first time, really, since the [Parkland] shooting,” Hogg says. Getting more people in office for the cause of gun violence prevention is a long-term goal of MFOL: Hogg mentions speaking with Jasper Martus while in Michigan, the 23-year-old Democrat who won a seat in the Michigan House of Representatives in the 2022 election. Martus, Hogg says, got involved in politics after participating in the first March for Our Lives at 17 years old.

Another win: In June 2022, Congress passed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which includes investments in community violence intervention programs and narrows the “boyfriend loophole” to prevent more domestic abusers from being able to purchase firearms (though not all). It was the first major piece of gun violence prevention legislation to be passed since the 1994 Federal Assault Weapons Ban. “We had brought … over 50 youth to D.C. that week to lobby,” Yahya says. And though she says it wasn’t the end-all, be-all solution, it was “a turning point where it’s like, Oh no, we could get things done at the federal level.”

Still, lobbying for gun violence prevention is often an uphill battle. Some U.S. lawmakers receive millions of dollars from the NRA, even as gun deaths in their states climb into the thousands each year. President Biden continues to draw criticism three years into his term for failing to live up to his campaign promises about gun violence prevention. All of this when, according to Pew Research Center, 63% of American adults want Congress to pass more gun violence legislation.

While it can be easy to dismiss activist efforts as futile, Hobbs makes clear that there’s a difference between March for Our Lives’ perceived failures and the failure of the political system at large to protect the people. “I don’t think we’ve had any failures [as an organization],” she says. “I don’t think that there’s anything we’ve not done to convey the seriousness and the urgency of gun violence prevention.”

The organizers are working to rally all Americans, on both sides of the political divide. The March for Our Lives stance remains that anyone at any time can be impacted by gun violence, so people across the country have a collective duty to act now. “A bullet doesn’t care who you voted for, and it doesn’t care who your kid voted for, either,” Hobbs says. “Bullets are very indiscriminate.”

Tyler, based in Arizona and Tennessee, says narratives that attempt to make gun violence a partisan issue are “quick ways to try to push down what this movement really is.” She says, “Our insistence [is] that this is bigger than just guns.”

“It’s a human rights issue,” Hobbs says. “I would hope you would be against kids being murdered in their schools [or] people shopping for groceries and being gunned down. If you don’t stand for that, then we already have something in common, ‘cause I don’t stand for it, either.”

Working to mobilize generations of supporters means taking pressure off young activists in their teens and 20s, who are often saddled with the burden of repairing past generations’ issues. The MFOL leadership is no stranger to this “the youth will save us all” mentality; even as I utter the phrase, some of them bite back smiles of recognition. “Some of us, when we started, were not even allowed to vote. Maybe even have a driver’s license,” Yahya points out. “Engaging in the democratic process as a young person is really, really difficult.”

One of those young organizers who has fought hard to have his voice heard is Trevon Bosley, who spoke at the 2018 march in D.C. Bosley also works as a B.R.A.V.E (Bold Resistance Against Violence Everywhere) Youth Leader in Chicago, where he remains committed to preventing gun violence in his community in honor of his cousin and brother, who were both shot and killed in 2005 and 2006, respectively. “The common misconception for most Black and brown communities is that whatever shooting went on, it was gang-related,” he says. “But for my brother, he was shot and killed at church.” The shooting wasn’t gang-related. “Same thing with my cousin and a lot of other people I know who’ve been killed in the inner city. You just want to put us in a box so you feel comfortable — so you don’t believe gun violence can be at your doorstep.”

The organizers are thoughtful about how white supremacy is inherently entangled in the issue of gun violence, pointing to the racist history of the Second Amendment and how “police violence is 1,000% gun violence,” in Hobbs’ words. “Policing has been used to essentially oppress and keep communities of color in a militarized state … under the guise of safety and order,” she says. “In order to eradicate gun violence, you have to be honest about what all gun violence is.” Black Americans are disproportionately affected by gun violence, especially police gun violence, according to Everytown for Gun Safety — they’re three times more likely than white Americans to be fatally shot by police.

Hogg highlights another social issue that affects gun violence: “90+% of these mass shooters are male,” he says. “Patriarchy and gun violence are completely intertwined, and we have to address that just as much as we also have to address mental health for the people that are dying from gun suicide.” While it’s great to see gun violence prevention being a women-led social movement, “we need to see more men in the fight as well.”

The march forward for these organizers will be a long, tedious one, but they’re up for the fight. They have to be. For them, there’s no other option. “I don’t have the luxury to not continue to work,” Bosley says. “People are still dying.”

“When I meet with families like the ones in Uvalde,” Hobbs says, “I realize that’s why you keep going. That’s why you don’t stop. Because that’s what [pro-gun lawmakers] want us to do. They want their inaction, their stubbornness, their arguments, their fight to cause us to give up and to quit. And I can’t. We can’t.”