After a year of delay, the 2020 Olympics are here and I (along with the rest of Gen Z) am freaking out. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been obsessed with them, because let’s face it, the Olympics are awesome. The top athletes from every country come to one location to compete against each other, sometimes in sports I’ve never heard of, and the winners bring fame and glory home to their country — yes please. There are unforgettable moments on the field, and apparently, juicy drama off of it.

While I spent an entire family vacation when I was 12 sitting inside watching the games, the Olympics aren’t as straightforward as they once were. As I’ve grown up, I’ve started to hear grumblings about the economic and environmental tolls that preparing for the Olympics takes on a country — I mean, building elaborate state-of-the-art stadiums that will only be used for two weeks obviously isn’t sustainable. This year, the Olympics pose an even greater ethical problem due to COVID-19, which has already delayed the games by a year and threatens Japan’s public health. Within the United States, our past and present of inequality makes me feel at best disillusioned and adds another layer to my now complicated feelings about this international competition. Nonetheless, the 2020 Olympics are happening in Tokyo, and as usual, they’re asking us to gloss over quite a few problems by focusing on shiny medals instead.

Between the problems associated with the Olympics and the United States’ domestic issues, it’s not obvious that my generation would be so excited about them. In general, younger generations feel less and less patriotic than older ones — a 2018 Gallup poll found that only 47% of U.S. adults are “extremely proud” to be American. But the Olympics seem to provide a brief break in the patriotism gap. I wouldn’t describe myself as patriotic, at least, not in the flag-waving, knows-all-the-words-to-the-national-anthem sense, but I’ve noticed that during the Olympics I feel a great sense of pride when I see athletes wearing red, white, and blue on the podium, and I’m not the only one.

“During the Olympics I associate America less with all that I criticize it for on a daily basis and more with the specific individuals competing who are representing the country.”

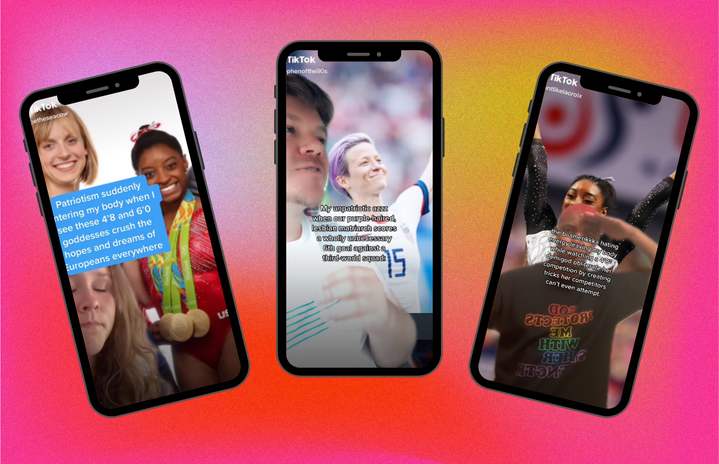

On TikTok, Gen Z made videos highlighting this phenomenon which mostly used a clip of comedian Joey Diaz telling people to “salute the flag.” Some of the TikToks were explicitly political, referencing racism in the U.S., while others focused on the excitement people feel because the U.S. tends to dominate the competition. Additionally, many users uploaded videos celebrating the shared identities between themselves and the athletes. Whether they’re tuning in to watch the U.S. obliterate another country in basketball or because they have a crush on Megan Rapinoe, it’s clear that Gen Z is excited for the summer games.

When I asked some members of Gen Z how they felt about the Olympics to see if they agreed with the sentiment of these TikToks, they responded with enthusiasm. Julia, 18 and a first-year at Wellesley College, is very excited for the Olympics, and even woke up at 4:30 a.m. to watch the United States women’s soccer team in their opening match versus Sweden. “During the Olympics I associate America less with all that I criticize it for on a daily basis and more with the specific individuals competing who are representing the country,” she tells Her Campus.

This sentiment was echoed by Halle, 20, and a junior at Wesleyan University who is most excited to watch gymnastics. “Usually I just feel mad at the United States for sucking so much, and [for] all the issues of inequality and injustice citizens face here,” she explains. “It feels good to see our citizens succeeding at things, and I do associate that success with patriotism.” The Olympics provide us with a break from focusing on the negatives and give us clear and exhilarating examples of positives coming from our country — photo finish victories, individuals overcoming personal adversity, and athletes standing up for justice on a global stage.

“In this case, being patriotic is about supporting people from the same place as you instead of saying you agree with everything your country stands for politically and historically.”

Eve, 21, and a senior at Wesleyan, explains the ways that patriotism changes for Gen Z during the Olympics. “In this case, being patriotic is about supporting people from the same place as you instead of saying you agree with everything your country stands for politically and historically,” she tells Her Campus.

She also says that the Olympics give the U.S. a chance to represent itself in a different light and distance itself from its biggest political actors. “I think sometimes it feels like America is defined only by its political figures, so for a few years it was like America was totally defined by Donald Trump and those that supported him,” she says. “The Olympics are exciting because America is able to present itself to the world in a new way and it’s refreshing to be associated with that instead.” I’d rather live in a world where the United States is defined by Simone Biles instead of Donald Trump, too.

Plus, it’s exciting to see people on screen from the same place as you. “In Vermont, every few years someone from our state makes it to the Olympics and I feel so proud,” Halle explains. “It’s nice to feel connected to the athletes. Even if they’re from another state, I can be like, ‘oh I know where that is’ or ‘I’ve been there before’ and feel a link to the athletes — being American is often that link, and that’s what makes me patriotic.”

“Feeling patriotic during these times can be dangerous, though, because you get so blinded by pride that you forget about all the things inside our country that are so horrible.”

Though she tends to feel more patriotic during the Olympics, Halle warns that we shouldn’t get too out of touch with reality. “I feel like feeling patriotic during these times can be dangerous, though, because you get so blinded by pride that you forget about all the things inside our country that are so horrible,” she says.

While Gen Z is most patriotic during the Olympics, they only mark two weeks out of the year every two years. The Olympics can be thrilling, giving us a much-desired time of celebration and camaraderie, but they have a dark side too. So many incredible athletes draw us to our television screens, but ultimately, the Olympics can’t diminish the political issues we face back home — so our patriotism is temporary, too.

Sources:

Jones, Jeffrey M. (2018). In U.S., Record-Low 47% Extremely Proud to Be Americans. Gallup.