By Reedah Hayder

It seems like almost every immigrant child is told when they grow up, they’ll be a doctor. It’s drilled into us from the very beginning. For me, I was fed the dream with my rotis and biryani.

My parents first moved to the United States from Pakistan, and then moved to Canada in 2001. Like most immigrants, my parents worked hard to make a place for themselves and their children on foreign land. Then, they pass the torch on to their children, expecting us to go so much further. Their expectations of six-figure salaries and well-established jobs are a tall order, and so often we’re faced with a decision: do I choose a career that appeases my parents or do I choose a career I’m passionate about?

This was a question that I asked myself many times as I neared the end of my high school career. I grew so anxious during my senior year just thinking about going to university. I looked to online research and questionnaires to somehow give me guidance.

I filled out hours worth of career questionnaires, but the answers were always the same: lawyer, accountant, actuary, criminologist, etc. The list goes on and on with the majority of the top picks for my match made careers being STEM careers. It wasn’t entirely shocking because the truth was that I was lying to myself. I kept filling out questions I knew would point me in this direction. I wanted to tell myself if I could just put in the effort, I’d excel at a more ‘reasonable’ career. A career that had better-guaranteed jobs, higher salaries and best of all, a set future.

So when applying for university programs, I went with programs like criminology and life sciences, rather than for programs that would excite me and would teach me to better my skills in a career that I’m actually passionate about. I told myself that the university level biology, chemistry and calculus courses that I hated sitting through was just me being lazy. That I wasn’t putting in enough of an effort. I told myself that hating those STEM courses was just a phase. University would be more fun, and I tried my best to convince myself that I would like it (as if science gets easier or better in university).

But I did all this because I wanted my parents to be proud of me. I wanted to say, “Yes, that’s me — [becoming] a future doctor is exactly what I want.”

So the deadline for university applications passed, June rolled around and acceptance letters started getting sent. I was accepted into all the programs that I applied for. But, upon opening my acceptance letters, I felt nothing but disappointment and regret. Grudgingly, I accepted the offer to study life sciences at University of Toronto. Both my two older sisters had gone into this program and they received the utmost respect from my parents for doing so.

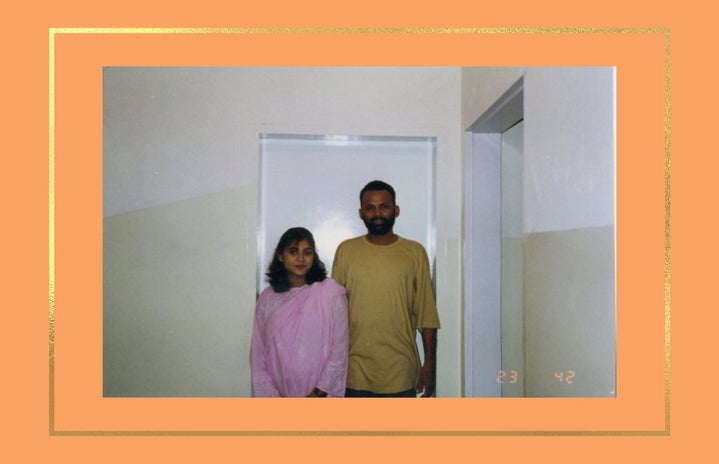

My two sisters, Shan-e Zehra and Sukhan Zehra, with me in the middle. Taken by my mother.

I was so anxious about the coming year because I always knew what I wanted to go into — and STEM wasn’t it. I just didn’t have the guts to admit it. Without telling my parents, I mustered up a journalism portfolio of a few pieces of my work and sent in the late application in June, hoping that by some chance, someone would believe that I had what it took.

Then it happened — I was accepted into the journalism program at Ryerson University. Many say the field of journalism is a dying one. Journalists don’t choose this career because it pays well, because it’s no secret that this isn’t where the money is. No, like most liberal arts students, we choose this career because we’re passionate about it.

So, what stops so many other second-generation immigrants from choosing a career they’re passionate about? It’s the fear of disappointing our parents that consumes us. Knowing that our parents sacrificed so much to come to a foreign land is a heavy burden to carry because every move you make, every mistake you make carries so much weight.

Many of us, as children of immigrants, find it hard to follow our dreams because more likely than not, it’s a whole lot different than what our parents had dreamed and wanted for us. Our parents came here with their main task being to survive. But we, as their children, are here to live. Immigrant parents make the sacrifices they need to make to make sure their children have a foundation to thrive and it’s our responsibility to make sure that their sacrifices are worth the courage they had to come here.

Hope and resilience are what best describe every immigrant’s journey and that’s what we carry with.