Edited by: Janani Mahadevan

Following the announcement of the lockdown earlier this year, I found a heap of chocolate-chip cookies on the back of a shelf. I was surprised; there was always no more than one pack of cookies allowed in the house – a strict rule enforced by my father. Upon further inspection, I found that the perpetually almost-empty shelves in my kitchen were suddenly stocked with piles of essential goods. A trip to the grocery store revealed another bizarre turn of events. Shopping carts were overflowing with packs of rice, flour, milk, and other essential goods. Shelves in stores were quickly emptying, prices of products were increasing, and panic had ensued. Mass amounts of products started to invade kitchens and storerooms of the general public. Amid the frightening outbreak of an unknown virus, panic-buying had become the new norm.

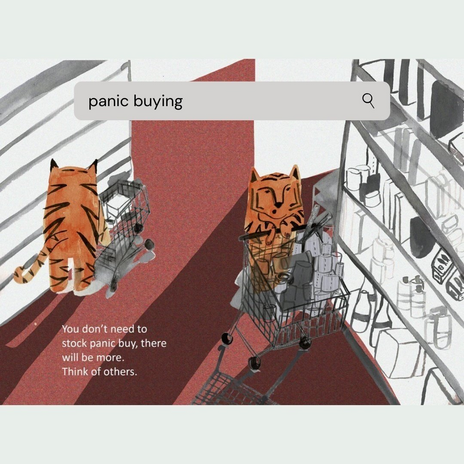

Panic-buying is a phenomenon in which people buy excessive quantities of essential goods in the face of a crisis. While people fought over the last bottle of milk and bought surplus packs of rice, many unfortunate people had to go home empty-handed due to stock unavailability. Moreover, few shopkeepers even engaged in price gouging, an illegal process by which sellers increase the prices of their products to an unreasonably high amount in order to maximize their profit. Controlling the mass panic that threatened any remaining space in the pantries of Indian households had become no easy task. People everywhere in India, from New Delhi to Tamil Nadu, violated lockdown protocols and social distancing rules to crowd supermarkets. Pantries, storage units, and cupboards became rapidly filled with enough items to survive a nuclear blast.

The COVID-19 pandemic is not the first time the world has encountered cases of panic-buying. It happened during the Spanish Flu of 1918. The SARS outbreak of 2003 also witnessed multiple instances. It has happened every time the general public has anticipated a disaster, and sometimes even after the disaster has already occurred. You may think it is perfectly rational to stock up on emergency supplies in light of a pandemic. If you ask me, a line is crossed into irrationality when you attempt to remodel your house into a doomsday bunker. Most importantly, hoarding supplies means snatching them from the hands of people who had the misfortune of getting there only after you did.

One of the main reasons people panic-buy is due to the anxiety that a rare calamity, such as a pandemic, produces in them. People, naturally, fear the unknown. If we cannot define or explain something, we cannot fight it. As the number of cases increased globally and those in power or authority consistently failed to provide immediate cure-all solutions, people, in response, grew increasingly apprehensive. They began to go to desperate lengths to assuage their feelings of anxiety: panic-buying, even if it meant being close to potentially infected people or waiting in long queues. Panic-buying is ultimately a mechanism by which people attempt to take charge of an uncontrollable situation. It shields them from spiraling into the dark hole of anxiety while facing a catastrophic event that is unfamiliar.

During the initial period of the lockdown, researchers proposed that appropriate reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic would be to practice social distancing, wear a face mask, and wash one’s hands with soap. Engaging in these behaviors would at least partially prevent the rapid spread of the virus. However, instances of panic-buying only increased all around the world, including India. To the layperson, wearing a mask or using soap was too simple a response to the massive panic and upheaval the COVID-19 pandemic had produced. A dramatic situation required a dramatic response, and panic-buying checked all the boxes in the eligibility criteria.

Another reason people panic-buy is due to loss aversion – a tendency to prefer evading loss than gaining a comparable profit. It feels better not to lose INR 500 than to gain INR 500. In a pandemic, people would rather overspend on large quantities of a product than risk not taking them in case it’s bought out entirely. Moreover, with the prices of goods increasing, people would feel more averse to losing an opportunity to buy a product at a lower price than waiting anxiously and risking an even higher cost.

Herd mentality – the tendency of an individual in a group to follow what the majority of the group does – also plays a significant role in perpetuating panic-buying. Simply being surrounded by or watching people who are engaging in this behavior can contribute to an increased false sense of scarcity of goods. When you believe something is scarce, you’d buy them even if you don’t really need them. Depictions of emptied shelves in grocery stores and panic-buying in the media further aggravate panic-buying, creating a sense of urgency that prompts individuals to hurriedly produce their own makeshift doomsday bunker.

While panic-buying brought me unprecedented piles of cookies to ravage on a Friday evening, it is possible that it prevented many homes from having a plate of hot rice every other day of the week. The COVID-19 pandemic is uncharted territory, and people are afraid. It might seem better to be safe than sorry regardless of the consequences. However, fear does not justify the fact that panic-buying risks the safety and livelihood of the general public. With climate change looming on humanity, a second pandemic is not unwarranted. A few strategies may be used to prevent cases of panic-buying in times of crisis. These include: (1) having an emergency supply of essential goods strictly limited to what is necessary, (2) being able to distinguish between rumors and factual information, and (3) relocating resources to obtaining professional mental healthcare in the case of anxiety instead of hoarding supplies. These solutions do not ensure an immediate eradication of panic-buying cases. They do, however, guarantee a noticeable decrease in the number of people crowding grocery stores, breaking lockdown protocols, and hoarding supplies amidst a pandemic.