Content and Trigger Warning: This article discusses mental illness and eating disorders. Please exercise caution while reading, and take care of your personal needs first.

I remember feeling the grooves of my checkered bathroom tiles on the back of my thighs. I remember the lime green tint of the walls and shower curtain. I remember the shocking sensation of a cold tear running down my hot cheek. I remember how the silence sucked even the emptiness out of the room. My throat was closed, my face was numb, and my heart was racing as I frantically tried to muster up every breath. I thought to myself, “This is what dying feels like.” I refused to put a label on what was happening to me, though in the back of my mind, I knew I was spiraling into my first panic attack. Perhaps I thought giving it a name would make it more real, or that I would actually have to deal with the pain I was enduring. I lived in fear of the reactions it would spur.

In my extroverted family, my life was broadcasted to everyone. My mother always provided the orange slices and Gatorade for my soccer matches while she sat and chatted with the other parents about the upcoming vacations we had planned. My father called all of our neighborhood swim meets and never missed a school play, sporting event or parent-teacher conference. My sister was a three-sport athlete who was destined to break our high school volleyball records. They were all loving but troubled in their own ways. My father was quick to get angery and slow to listen. My mother buried herself in work and wine. My sister was angry at the world for the shoes she was told to fill. I was destined to graduate high school as the Student Body President, a National Honors Society member and with a 4.0 GPA to go on to make something of myself at a prestigious university. It felt as if my destiny was pre-decided by my family as an effort to leave a legacy for our last name. They all pushed me towards these goals, and eventually to the end of my limits. My destiny became my idol. Interwoven with it were my image, my drive, and my high-functioning anxiety.

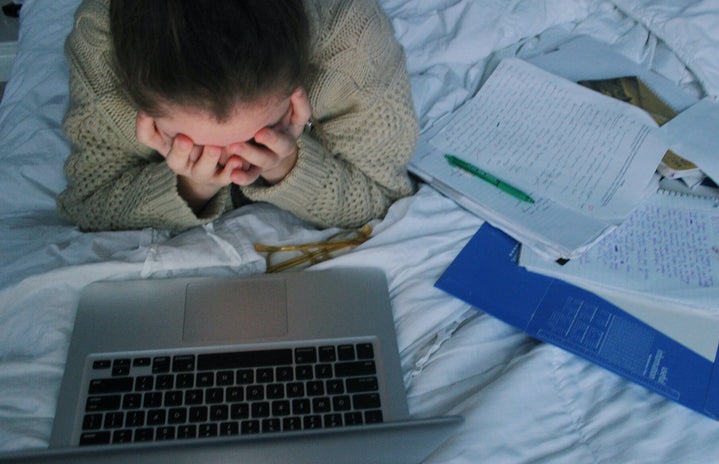

My anxiety took a drastic turn when, in my junior year of high school, I began having frequent and severe panic attacks. However, I refused to speak about it to anyone. I feared that I was abnormal, struggling on my own. At times it felt like my head was submerged, and no matter how hard I tried, I wasn’t able to claw through the school work, friend hardships, body image issues, and stress to get to the surface. I ached for someone to talk to, for someone to throw me a life vest, even just for a moment. I hoped that by opening my mouth at our family’s Sunday dinner, the words would flood out of me, but all that fell out was “I’m doing good,” followed by crying myself to sleep every night, hoping someone would hear and come to my rescue. So, I learned how to hide everything going on in my head and bury it within the depths of myself. I didn’t know that burying it beneath my seemingly perfect exterior meant that it would seep into all of the cracks and crevices within me. I lived under constant pressure, trying to find a release, looking for something I could control. I found this in calorie counting, daily weigh-ins on my parents’ scale, and hiring a personal trainer. Little did I know, my ill-willed attempts at survival only made the cracks deeper and increasingly harder to fill.

I started opening up to one of my friends and my father, both of whom answered my statements with “What is there to be anxious about? Aren’t you doing well in school? Have you tried breathing through it?” I found that not only could I not understand what was going on inside my head, no one else could either. My fear that I would fail at trying to be perfect was coupled with no one knowing how to throw me a life preserver as I faded deeper into the water. By the end of high school, I had achieved everything I was destined to. I was considered worthwhile, for a time. I was then placed into one of the top universities nationwide. Suddenly, I became another number in the crowd. However, there is something to be said about the comfort I found in being another passing face — no expectations being set for me, nobody making a tally of my failures, no more broadcasting my life from the sidelines. I was free, but my brain still kept my thoughts in chains, not allowing them to roam into total satisfaction and comfort. It kept me questioning, doubting that what I was doing was enough. Though I was doing well in my classes, had a large circle of friends, and was making my parents proud, there were days where I felt as empty as I did on my bathroom floor junior year. There were days where all I wanted to do was cry, so disappointed that this is where all of my decisions had led me. Then, on the other hand, there were days when all I could do was dance with my friends in the street, so overjoyed with how well life had treated me. I had never felt euphoria and melancholy so closely intertwined into my daily life. My thoughts felt as jumbled and confusing as my words do as I try to explain them today. This is to say, feeling better is not to be confused with ridding anxiety. Having good days is not to be confused with the long journey of healing.

I wish more than anything that there was a concise end to this story. I wish these urges would’ve stopped or that the panic attacks would cease. I wish that I could say I started to get gradually better and feel like my vast ocean of anxiety shrunk into a puddle, but that would be a lie. What’s true is this: I’ve learned I’m not abnormal. I’ve learned I don’t have to be impressive to be worthwhile. I’ve learned to be vulnerable. I was taught this by a mother who sits with me on the phone as I cry and heave from my internal, overwhelming sense of failure. I was taught this by a sister who rarely calls, but tells my parents how proud she is to have me as her older sibling. I was taught this by a father who learned how to have open conversations about the not-so-polished parts of myself. I was taught this by a best friend who picked up my broken pieces and called them beautiful. My journey isn’t over yet, but I have learned how to endure the lowest valleys and celebrate the highest mountains.