Maybe “lies” is a bit of a dramatic way to put it, but it was actually John Green who put the idea in my head. Green has often joked on his Vlogbrothers YouTube channel that storytelling (at least fiction storytelling) is just lying. But in an interview with author and blogger Justine Larbalestier, he also admits “the mere ability to lie well is not the same thing as being able to write good fiction,” and I agree.

However, Green may be onto something. Good liars and storytellers have one essential thing in common: they are compelling.

Now, I do not condone lying—I firmly believe that honesty is the best policy. But these days, we are exposed to an enormous amount of inventive, speculative and imaginative storytelling. Stories that are so engrossing, we go along with them and start believing in them as though they are feasible in real life, no matter how far-fetched they may be.

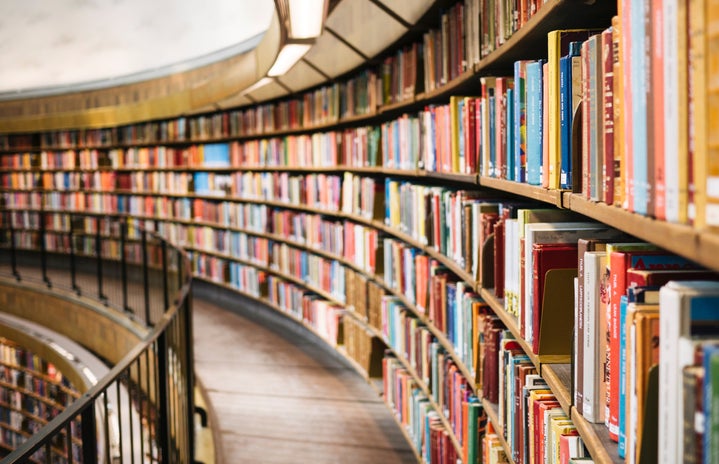

We’ve been telling stories for as long as we, as humans, have had the ability to communicate. It was a master storyteller, Philip Pullman, who said: “After nourishment, shelter and companionship, stories are the thing we need most in the world.”

Many studies have been done on the effects that stories have on the human brain and body. According to UC Berkeley, the neurochemical oxytocin is responsible for empathy and narrative transportation. It is naturally produced in the brain when we are shown love or trust in real life, and the same happens when we witness these emotions in a narrative, not just in person.

According to the Harvard Business Review, character-driven stories have the same effect that real life relationships and situations do. We love connecting with characters—reveling in their triumphs, sympathizing with their tribulations, and even finding elements of ourselves in them. We love the feeling of suspense, to eventually find out just how satisfying (or frustrating) the ultimate payoff can be.

At certain moments in our lives, we can rely on stories to escape reality, to transport us to places we didn’t even know we could dream of. Fiction helps us to imagine the possibility of something beyond our realities. The story doesn’t have to be logical; it just has to make us feel.

These statements are truisms that many people can relate to without questioning them. There are those who will take advantage of the power of storytelling and its emotional appeal. For example, politicians, advertisers and marketing agencies have studied methods of western storytelling that’ve been passed down through western history to manipulate audiences for their benefit.

Aristotle posited that “plot, characters, diction, thought, spectacle and melody” were all factors in leading audiences of the Greek theatre through katharsis, or purging. On a greater scale, religious stories influenced people’s lives – with the rise of the Catholic Church in Europe, teachings and stories from the Bible were examples of influential literature.

Nowadays, the public’s daily decisions and habits are influenced by stories told through every medium; from the glamorous lifestyles seen on billboards and Instagram, to the sympathy-seeking anecdotes of politicians and even reality T.V. contestants. All of this persuasion is done to gain numbers—be it sales, followers, voters or viewers.

When thinking about storytelling as a means of influence, it is easier to understand how storytelling can be considered lying. Is that certain perfume going to bring us closer to living a life full of laughter and love? Is everything politicians say true? Maybe there is truth in these instances, but chances are, some things are simply made up in order to influence an audience’s actions. And sometimes we let them, despite our better judgment, because the story is just that good.

Sometimes the influential power of storytelling is harmless, and it can simply be a great way to pass the time. Other times, crafting stories may have a potentially malicious purpose.

So why do we continuously insist on leaving our understanding of reality at the door before diving in and accepting the arbitrarily invented rules of a new world? The next time you’re binging episode after episode of a new Netflix obsession, or gripping the edge of the plush, folding seat in a darkened movie theatre, or maybe just curled up on a sunny afternoon with a page-turner and a mug of tea, ask yourself how you feel, and maybe you’ll have your answer.