Learning is the inception of liberation. While engaging in education, I remove myself from the unnecessary noise and commotional riff-raff of Gen Z, from the opinions that others say matter and the opinions that others say don’t. Free from the outer world, I am gladly and freely trapped in my sphere and enthusiasm. In summation, throwing myself into the realm of intellect has always been my happy place, my most beloved intangible location, both singular and multiple simultaneously. It is a center that calms calamity with inquisitiveness. Magically, education is both an act and a location, something one does, and a curiosity cache–desperate and enthused to be penetrated with the sharp end of one’s mind. In short, it is an act I am ready for before it even makes itself known. Instead, the active state of my curiosity makes education feel imminent, and a location that I travel to, without question, to both revel in my authenticity and when times get tough.

The comfort and act of self-identification with education stems back to my high school years. Attending a small, private, fine arts school, we were encouraged to make cross-connections between academic realms, championing and reveling in the interdisciplinary, our implicit scholastic motto “the more the merrier.” The more that I explored, the more I found the act of educational engagement far more rewarding than any grade or award. We had no valedictorian, and we had no traditional grading system. Instead, after years of homeschooling, my reintroduction to the world of intellect and curiosity-led enthusiasm was through the conditioned act of learning for exploration and for what we loved instead of learning to become the school’s next Harvard contender. As an autistic individual, my high school’s learning environment was ideal for me–holistic yet challenging, creative yet traditional, and above all, asserting the importance of compassion within education. Even socially, most students were accepting of my differences, laughing at my jokes, and, with a seemingly attentive ear, listening to my thoughts, even in my heterogeneously autistic state. In all, I hardly ever felt left behind, yet in a realm of my own, understanding myself but not understanding others. Separation never seemed substantially present, but perhaps living in my sphere of fine artists who mastered calligraphy and pointillism in sixth grade and holistic STEM hopefuls did not show me all that the world was.

My crisis of identity and academia was a brutally imperfect and chaotic beginning. An introduction to college, where the world grew bigger and suddenly, I grew smaller–a collegiate, coming-of-age Benjamin Buttoning. Now introduced to grades as well as an expanded student body, my quirky brain began to feel overwhelmed, swept up in a desire to prove myself, amidst a sea of peers who seemed to have it all figured out. I spent many Friday nights reading treatises from the 1800s and writing essays about The Iliad while others spent it laughing with friends and going out. College was a weird world compared to high school. I had never felt as much of an autistic isolation in high school as I had felt in college. Now, my autism felt distinctly like the cranial elephant in the room. My peers laughed at jokes I didn’t comprehend, grew and sustained friendships out of shallow forms of connection and humor that I didn’t understand could qualify as deep or marked with meaning. College felt like a world in which the only time I could fully comprehend what was happening around me was inside the classroom, where I understood the distraughtness of Shakespeare’s lovelorn soul and the incoherent but eloquent mumblings of Derrida. Despite the prodigious atheist within me, I comprehended the exceedingly Christian theology of Milton more than the behavior of my Gen Z counterparts.

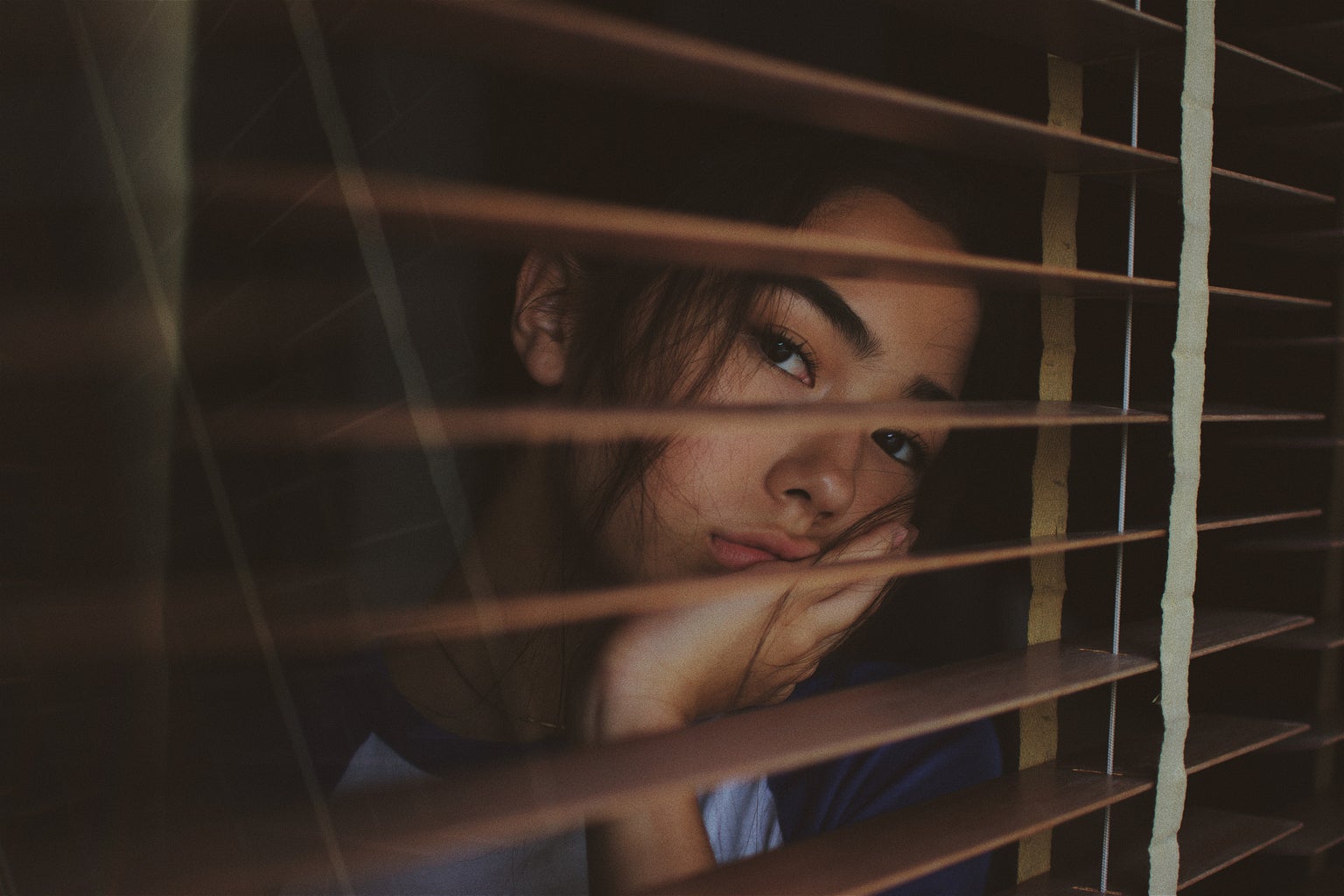

My fixations on grades were an attempt to assimilate an identity that made my separation from others at college–of my generation–feel like a powerful sassy squawk at the zeitgeist that made my autism heave and wheeze in a fit of autistic asthma. As one Friday alone turned into another, I began to understand that my pursuit of A’s was zealousness disguised as commiseration. It was a pursuit of my desperation to befriend, now directed towards accolades and an award-studded identity, rather than a peer. The further along in college I was, the more I began to fully understand that I grasped for exceptional grades and awards as a way to have something to hold onto when it felt like everything around me in college had been broken in front of me before I could grab hold, screwing me of stability. In my autistic state, college was my social purgatory, a macroscale inferno–hordes of the inhospitable, people that I felt I was at a loss for understanding. I was engulfed in a constant state of misunderstanding–from both their communication and social habits, as well as a misunderstanding of why I simply could not understand them myself. I was considerably septuagenarian, in a sea of boomer oblivion and ignorance. More than that, I felt lost in a sea of neurotypicality, and I felt as if I were like a piece of litter thrown in the water, floating but most definitely not belonging in the clean aquatic sentience.

I fully, continually, and obsessively embraced my self-created label of “serious student,” curating an identity that managed to put a positive spin on my separation from the general population of my campus, so that every time, with each millisecond of its familiar melancholic note, I wouldn’t be reminded of the truth I felt that led me down a dangerous path of self-criticism. I aced papers, tests, and creative assignments and built up a portfolio of academic prowess while still feeling a constant separation from the students themselves.

Fundamentally, labeling myself as a “serious student” stemmed from a serious problem. I was fixating on actions that led to trivial results (grades, in the long term), to separate myself further from the collegiate idiocracy, to convince myself that the separation, disguised as academic strength, came from the presence of my unique genius amongst the crowds. I stood out like a sore thumb, destined for later life, ripening for the fall of my years. Yet it was springtime in my collegiate world, and I, the erudite apple, fantastic but self-conscious, was in a harvest. I was out of place in the midst of blossoms. I was a season that came too soon, the oh-so early autumn. In short, I was in my own internal theater of autism, engaging in a production entitled A Positive Spin on Separation, a show sold out to me and only me, all the seats used up by the individuals who made up my mental capacity. All to convince myself of the undeniability and positivity of that very truth, performing so well that perhaps it was the autistic processing Meryl Streep.

As much as college differed from high school, my love for learning was my main tool for getting by when all else of college disappointed me. My facade’s extremity had garnered me a perfect transcript, but nonetheless, still an imperfect soul, impacted by the cacophony of campus around me. It felt as if my brain was short-circuiting in the realm of collegiate socializing. I clung even harder to my identity of false security. I told myself that it was my state of genius, my fundamental tendency to interact through a guise of “PhDness,” that separated me from my peers. I used my “serious student” identity, more than anything, to ignore the separation between my neurodivergence and the neurotypicality of my peers, as if acknowledging my differences was a negative thing at all. Perhaps I was scared to fully accept that I was different. Perhaps what terrified me most was an acknowledgment of my difference that turned into a personal reclamation of the very word itself. Perhaps, if I learned to love what different meant to me–how difference itself defined me–then I no longer would have an excuse to be comfortable in unnecessary suffering, a state I had become dramatically and unnecessarily dependent on.

Indeed, it seemed that my portrayal was more of a denial. The more I transformed into my character of “serious student,” the more I realized that getting straight A’s was a separation that wasn’t awe-inspiringly self-empowering, fully a positive reclamation, or a natural behavior stemming from the classically conditioned state of my slightly MadHattery genius. The label, the act of defining myself obsessively as this one persona, was a separation that, above all, simply made the gap between my peers and I larger. If, in the only way of difference, there were grounds for a sensation of separation, my self-inflicted state of prodigious difference made me feel more Rory Gilmore than a reject or a wallflower. Reclaiming my difference was both an act that terrified me and a persona that saved my mind from the troubles of having to comprehend that my vulnerable autistic state was the very root of my genius and that I spent too much time haphazardly creating out of manic desperation and falsity. I spent my time fashioning an awful imitation when in reality I had the greatest genuinity, instead locking it away in my mind’s metaphorical cabinet for so-called “safe storage,” when really it was done in an attempt to follow and idolize ignorance.

In high school, I had learned without attaching a label to my love, a fundamentally healthier alternative to the present moment. Yet in the present, I had traded in the treasured laissez-faire of my academic past for the security identity of my present, to keep myself safe from the confusion I digested through my observations and experiences and internalized as pain. Instead, silently, in between illustrating my understanding of Judith Butler and Michel Foucault, either through words spoken or written, I wanted to be the “perfect student,” “straight-laced”, the “good girl”, for there was something protective, bizarrely empowering, reverence about being the girl who rejected lemming-hood. If I isolated myself, I had control, a fragment of power.

Self-isolation had a certain power to it, and although chilling and solitary, I was able to control being removed–alone–controlling my presence and status overall among the populations I eased in and out of, instead of others being able to exercise their control and isolate me. If I was alone, it was out of choice rather than exclusion, an event so experienced and feared that it was the “he who shall not be named” of my inner autistic Hogwarts-verse. Viewing myself as a “serious student” was attempting to give life to the idea of designating myself as prodigious, above everyone, on another plane–not below and discarded. Academically pushing myself to the absolute limits was an act in which I bequeathed myself with unparalleled academic agility to see a sunrise of potential on my future, to bestow upon myself hope and belief in the hardship of my present. Isolation inflicted by an “other” was a far more detested, vile, and solitary feeling than I myself choosing the solitary. I could find and read both the fantastic and the false in human nature, a consistent gift and struggle, a spectrum that saw endless potential in beating hearts underneath all the Lulu Lemon, and yet so much falsity in their smiles and conversations. I saw potential but rarely had satisfaction with peers, because despondency always followed when one, like myself, saw the world through the lens of what could be. I frustrated myself, and confused myself did I have high standards, or was I simply a blunt but truthful observer of and through reality, reconciling with my belief’s inability to be worldly manifested? The frankness I saw and internalized separated me more from the rewarded mendacity around me. Once again, I threw myself back into my identity. By labeling myself and throwing myself into a world of letters that were symbolic of an identity of effort, A’s and 4.0s were the ideal achievement for me; an A was a method to achieve, a simple but meaningful letter that tangibly marked and proved the worth of myself, amidst a collegiate universe, where each day was struck by doubt left to pile in the autism trash can of my mind, rotting.

Each day the struggle between being a lover of learning and being my autism’s archetype of the “serious student” confuses and attracts my identity of who or what to be. Despite this, I feel that I have come to understand my fixation, perfectionism, and my curated obsessive identity as a subconscious denial of my difference. I have begun to explore the depths of difference and what it means, penetrating the confines of connotation to a universe in which the innate difference in the definition of the word itself is a positive although silent form of potential for self-reclamation and definition waiting to happen.

While I will always care about learning and about my studies, I have found that traveling back to the roots of my love for learning as a process rather than a grade is fundamental to living as my most successfully autistic self. To approach learning as a process rather than an outcome is to approach learning as just that–learning. By letting go of an identity created to protect through a tedious denial, I learned to embrace the potential in difference, in being different, and in learning what that potential is. Awkwardly, amidst a crisis of self-struggle, I Frankensteined myself, creating a monster out of self-denial, protection, perfection, isolation, and separation, creating more distress than success. Now, I am instead learning to learn about my differences, just as I loved to learn in high school–unattached from tangible but meaningless labels, awards, and acknowledgments. It was only when I explored the intangible that I found the divine in the undefined, the active, the experience, the process, and the enthusiasm.

I feel profoundly appreciative of my autism. Although I may be unsure as I act and plan, I look at life by idolizing and observing the minuscule, of which there are infinite, and thus of which my zest and love for life are infinite. I am constantly learning the quirks, opening myself up to them, and am undefined yet simultaneously existing as and embodying the quirks themselves. I love every minute of being a brain that manifests an active state, but in body, is wonderfully undefined, a student, woman, and a human of quirks, depth, and limitless purpose and potential.