The first time I attended a philosophy class at CU, I felt a wide range of emotions: excitement, fear, and happiness. I sat in my seat, eager to finally attend my first official college class and the first one for my major. It was a Monday at 9 a.m., but I could already feel myself becoming a real academic. My pen flew as I noted every single word my professor uttered, not yet knowing the proper note-taking strategies. Freshman me was full of hope and ready to learn, but as time went on, I felt the drive start to slip. At first, I chalked it up to the expected nerves and stress, but I soon realized it was much deeper than that.

Maybe it was because I was in a room full of people as smart, if not more, intelligent as I was, but I started to feel small in the classroom. Suddenly, from an inner voice that wasn’t my own, I began to be insulted. You sound stupid. Black people shouldn’t be in this type of space. Women aren’t as good at this anyway.

I started to participate less and only listened passively: my grades dipped as a result.

I didn’t understand where the voice in my head was coming from. Until that point, I had never thought these things about myself. Sure, I sometimes felt self-doubt, but never to the extent I did once my troubling thoughts started. In fact, I was brought up to believe the opposite: I was smart, black people can do anything, and women can be good at whatever they want to be good at. So why was my mind spewing such vile thoughts?

Upon some recent reflection, I realized the false, oppressive ideas of the dominant society had suddenly infringed on my consciousness like a pack of dogs, tearing apart my positive sense of self. I had internalized the oppressive attitudes and beliefs about my social groups completely against my will. Although I didn’t have a name for it at the time, I was experiencing internalized oppression.

According to Karen Suyemoto, a professor in Psychology and Asian American studies at the University of Massachusetts, internalized oppression is the unconscious internalization of false ideas about one’s own marginalized group(s) and themselves. In my case, I unintentionally grew to accept the beliefs about my marginalized identities as both a woman and a black person in a predominately white society.

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated phenomenon. Many people from marginalized groups have experienced internalized oppression, and, similar to my case, it can have negative effects on their learning in educational settings.

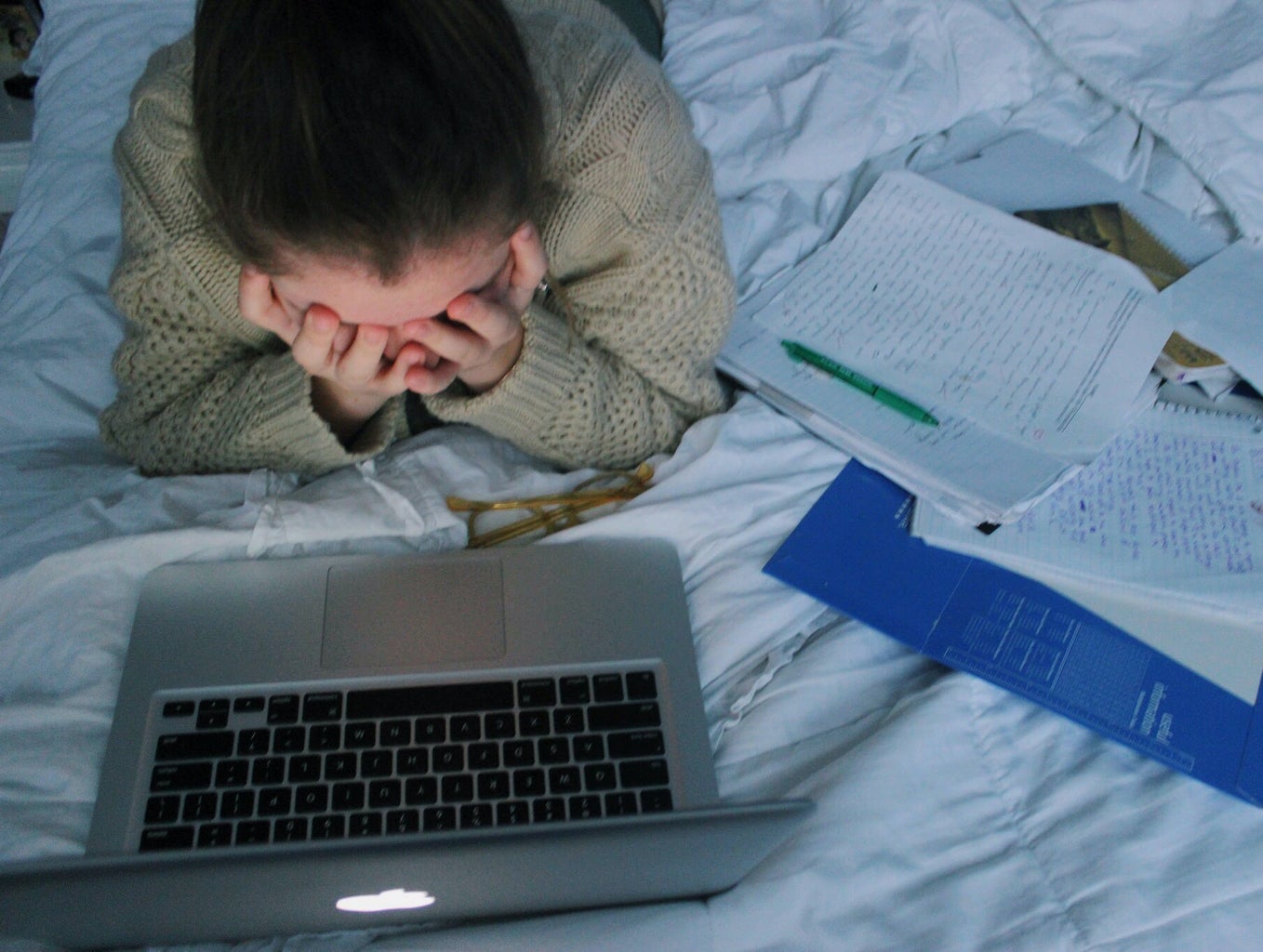

My experience with internalized oppression made me not want to continue pursuing higher education all together. I stopped asking questions in class, put less effort into assignments, and had more absences than ever before. This spiral, of course, impacted my mental health extensively, only serving to worsen the problem.

In the back of my mind, no amount of determination would prove those beliefs false. Any setback, like a slightly bad grade or critical comment, would only serve to reaffirm my false yet powerful beliefs. Not to mention, I thought I was alone in this experience since my peers and professors weren’t discussing it. If I had been made aware of what it was and how it could affect me, I believe I wouldn’t have had as hard of a time dealing with it.

Although I was able to pull through and do well in my classes, internalized oppression and a lack of discussions about it made succeeding significantly harder. It felt like putting in the effort was futile, as I had internalized false biases and subconsciously believed them as true. This only continued into future semesters and classes, disguised as stress from course load.

Internalized oppression and stereotype threat, another close phenomenon, and their relationship with education have been studied. In chapter nine of Dr. Claude Steele’s book, “Whistling Vivaldi,” he recounts stories showing how internalized oppression can impact student performance in educational spaces. These stories relate more directly to stereotype threat, but I will use Steele’s own experience to show the possible impacts of internalized oppression.

One story, from the perspective of Steele himself, describes how being one of the only black students in a graduate psychology program impacted his perception of himself and black people in general. He questioned whether the oppressive beliefs about black people’s intellectual ability were as true as oppressive society said they were. This led to him feeling hesitant to ask questions in class. This experience’s impact on his participation could have been a factor that negatively impacted his learning, given that he may not have gotten his questions answered or generally had the support he needed.

However, Dr. Steele, along with other researchers, found that intervention strategies like establishing trust through relationships, self-affirmation, and generating discussions about growth mindset and student-centered teaching could help to mitigate the impacts of internalized oppression in education. In one of the experiments, Steele found that when students of marginalized identities were encouraged to self-affirm prior to an exam, their scores increased compared to when they took it without self-affirming. Although these strategies are more directly related to stereotype threat, they could still be helpful for internalized oppression due to the concept’s close proximity to one another.

Students, like myself, in educational settings could benefit from these intervention strategies, whether they have experienced internalized oppression or not. However, I think they’re especially important for students in marginalized communities since they address some of the aspects that make internalized oppression so impactful on education.

In my experience, I was able to find trust in my community, which helped me to understand what I was going through and set me back on the right path toward my goals. With time, I was able to quiet the oppressive voice in my mind and understand its presence had nothing to do with my ability or worth: these thoughts are simply the remnants of false, stereotypical beliefs covertly perpetuated in society.

We must incorporate discussions about internalized oppression into educational spaces as a way of making education more inclusive and accessible to individuals from marginalized groups. Like me, many students often don’t understand what they’re feeling or why, especially given the unconscious nature of internalized oppression.

By having these conversations about internal biases, we can make ourselves and our peers feel less isolated and hopefully spare them some of the pain of internalized oppression by sharing intervention strategies and bringing awareness to educational spaces. Learning about internalized oppression helped me reconnect with my love for learning, and I hope this knowledge will help others in their time of need.