There is something morbid about the way that parents have to have conversations about race with their children. While I’m not Black, I’m the children of immigrants, and I went through the public school system as a young Muslim girl. I was nine when I was told that I wasn’t really “from here” and twelve when I was first called a terrorist; I consider myself lucky. Muslim girls who wear hijabs have experienced worse for longer, and I know friends who’ve told me that their parents practiced snatching off their hijabs to train them how to react, because it is the kind of preventative measure that people of color need to take, even in childhood.

It is informed by these experiences that I write today. People of color and of religious minorities have been having traumatizing conversations with their children for a long time, and we grew into adults with relentless anxiety. One thing unique to our generation is the level to which we are forced to confront violence. Smartphones, data, and widespread Internet have allowed for the proliferation of social media, so much so that online events seem to govern our lives in a tangible way. Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and Snapchat have created a pervasive awareness that has fundamentally altered who we are—experts say that our heart rates increase when we get notifications. We obsessively check our phones, even when we don’t hear notifications, because technology and the internet is the medium on which a lot of social interaction happens now. So what to do in the middle of a crisis, when the social fabric that connects to one another is entrenched with violence?

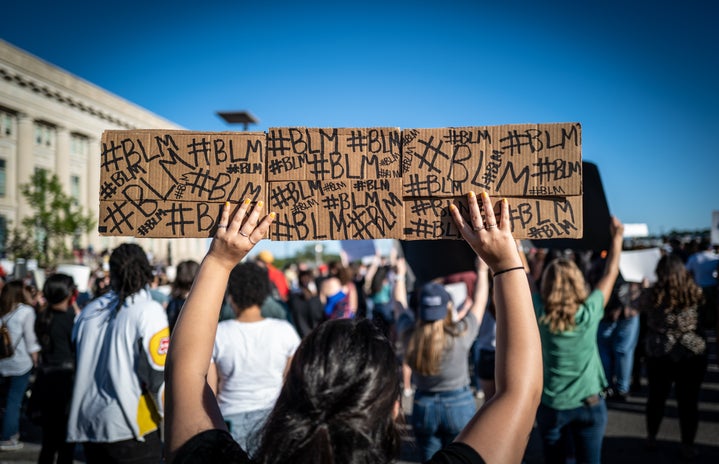

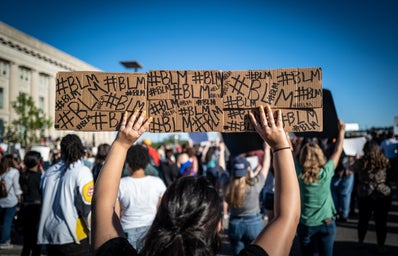

Being a woman, specifically a woman of color, online is already difficult. But I am worried for today’s youth. I am terrified for George Floyd’s daughter, who is going to grow up in a world where her father’s murder is public information, where every agonizing moment of the encounter is captured on video. The last surge of the Black Lives Matter movement got us body cameras. But we already had documentation, everything from the famous picture of the scars on Gordon’s back to the videos of people being knocked down by high-pressure fire hoses in the 60’s. It makes me wonder if videos of police brutality are the new hijab-snatching; if kids are learning about what can happen to them on Instagram and TikTok instead of sobering conversations with their parents.

It has always confused me why videos were needed to spark the movement. I have been entrenched in activism throughout middle and high school because of the things people said to me as a child—but even I grew up feeling like I could exhale at home, like there were mosques and other Bengali people’s homes for me to fully be myself in. What worries me is that digital spaces wrap around us. We are constantly surrounded by social media, and it will fundamentally change the chemistry of the new generation to be hyper-surveilled and aware of the danger they are in, simply existing by themselves. It strikes me as hypocritical that videos of white journalists being beheaded by ISIS were taken down everywhere as part of an effort to leave them with dignity. In America, we need to broadcast death, to record the police beating people a hundred different ways, in order to see a change in the way we govern ourselves.

There is a note of hope throughout all of this. Social media has given us a much needed media egalitarianism; we don’t need to look at the deceased’s mugshot on the news anymore. Instead, pictures of snatched faces and senior photos are candles at a virtual vigil, and eulogies stretch years as our condolences to the deceased are repeated. Although I know there is an inevitable day when Gianna Floyd will learn the truth about her father—his name has been immortalized, stark text on the backgrounds of timelines everywhere as she repeats what she learned when he died: that “Daddy changed the world.”