The first banned book I read was “To Kill A Mockingbird” by Harper Lee in eighth grade. The book was assigned to my English course, and while I don’t remember the many details of the book or even the class discussions, I can still remember the feeling of being in that classroom. For a book discussing racial inequality and sexual assault, the content didn’t worry me, but my peers did. I remember being the only Black student surrounded by my all-white classmates. I remember the substitute teacher who made sure to never skip over the racial slurs in the novel. While I knew they weren’t being hurled at me personally, I felt deep discomfort hearing it come from this white man’s mouth. Yet despite these intermittent feelings of uneasiness, it was the only book that year that elicited deep emotions from me.

The second banned book I read was “Catcher in the Rye” by J.D. Sallinger in ninth grade of high school. While we as readers can sit here and discuss whether or not Holden Caulfield is a horrible fictional character or not, that’s not the point here. Upon first reading the book, I thoroughly enjoyed it. It was the first book where the class discussions captivated me. I had a teacher that challenged my peers and me and often would pit us against each other to find supporting evidence in the text to make our claims. I remember this book being the first that was critically analyzed and suddenly English was more than just simple factors of liking the book or not but looking for themes and literary techniques. Suddenly, the whole subject of English was cracked open for me, and I craved more of that feeling.

The third banned book I read was part of a long slew of other banned books I read my junior year of high school. That year, I decided to take a course called Politics and Minority Art. This was the first time that I had ever read literary novels and memoirs by Black authors about Black life. It’s where I discovered Richard Wright, Toni Morrison, and Zora Neal Hurston, all authors that at some point in time I’ve included in my Her Campus articles. I remember reading “Black Boy” and thinking “Where has this book been all my life?” When I read “The Bluest Eye” for the first time, Toni Morrison’s work completely tore me apart emotionally with its relatability and threads of disturbing plot points. But at the end of the day, I remember thinking, “How had I gone 16 years without knowing who she was?”

That class allowed me to see myself reflected back in a text. I remember falling in love with Wright’s writing style and his ability to speak his mind unfiltered. I remember my English teacher allowing me to excel in that class by bringing the Black experience into the conversation, as one of the few Black students present in the course. I recall the white discomfort of my peers, and for once, I didn’t care because the cultural and intellectual capital was more than worth it to me. And I remember thinking of all the white authors I had read in school, from Shakespeare to Harper Lee to Sallinger, and not once complaining about the centering of white narratives, when I had every right to. Those books gave me permission to explore other narratives outside of my own. They challenged the ideology that I had which had so much been shaped by the people around me.

I once had a professor that told me if your writing is upsetting people you were doing something right. While book bans are nothing new in America, to live in the year 2022 and to witness the censoring of expression is, to put it frankly, terrifying. Because I can’t help but think how different my life would have been had I not read the books that I did in school and ventured out to find myself. The point I want to make is that despite times of discomfort, each book that I read shaped me into not just the thinker I am but the person I am today. Simply put, I probably wouldn’t be the writer I am today had I not been exposed to those books. More importantly, books helped me realize what a privilege it is to read about the marginalized experiences of others without having to endure the experiences firsthand.

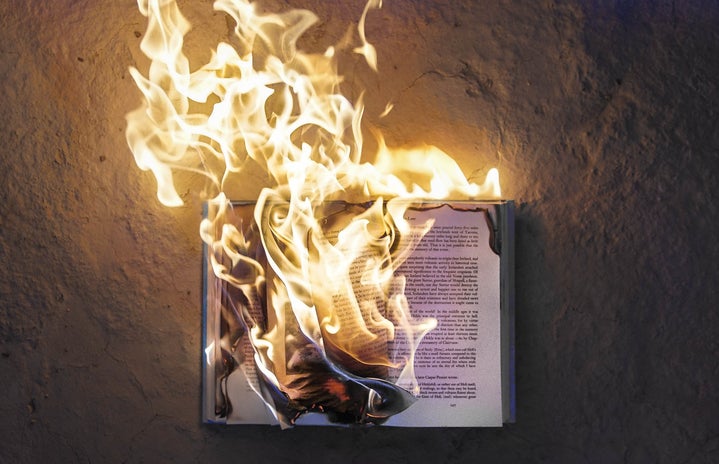

To ban books is to restrict the ways our youth discover the truth about who they are, what they believe, and more importantly the truth about the society they live in. So I get it. The idea of this progressive, diverse, and innovative generation on the rise in America uncovering all its tortuous past that permeates so much of the present and demanding more must be terrifying to those who would rather things remain the way they are. However, banning books won’t stop this effect from happening. Banning books simply makes it more difficult for people to obtain them because not every child has the ability to purchase or access a library with such stories. Banning books at the end of the day belongs to a long legacy of conservative ideology that attempts to rewrite ahistorical narratives in the American education system. As the author of “Fahrenheit 451,” Ray Bradbury, said, “You don’t have to burn books to destroy a culture. Just get people to stop reading them.”

I don’t have all the solutions, but I do know this. If you can purchase books that are under attack right now, do so for the families and children who cannot. My high school English teacher, unbeknownst to them, gave me the books to change my universe, and what a beautiful opportunity that would be to give that experience to someone else.