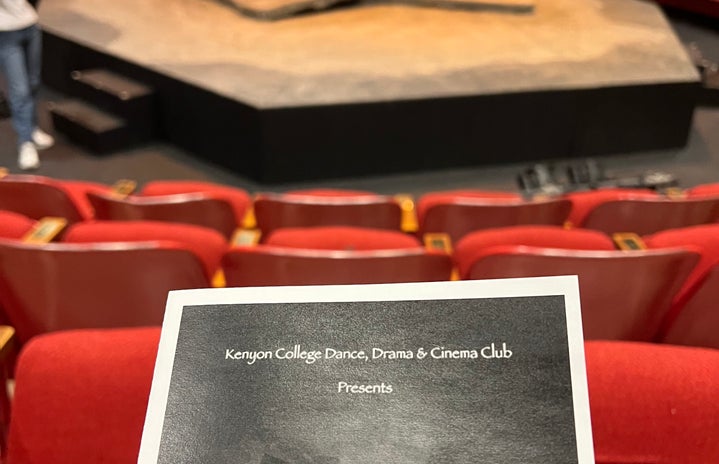

On a cold and hectic Friday night this semester, I went to watch Kenyon College Dance, Drama & Cinema Club’s play Battlefield directed by Professor Jonathan Tazewell, shown on the Bolton Theatre stage. Battlefield is a one-hour play, adapted from Jean-Claude Carriere’s eleven-hour play Le Mahabharata, which itself is based on the major Hindu epic. With my busy academic and extracurricular schedule, I usually (unfortunately) do not go to the plays or concerts put on by Kenyon’s wonderful Dance, Drama, Film department unless my friends are in the pieces. When it came to this play though, I knew I had to be there. I grew up with The Mahabharata, cherishing the lessons it taught, and so of course I marked the Friday showing in my calendar as I genuinely wanted to support this epical story being shared at my predominantly white institution. The fact that my roommate had been cast in the show was just another cherry-on-top. I was looking forward to supporting my roommate in this endeavor and excited to see this play performed.

Before I went to watch the play, I was intrigued about how Indian culture and traditions would be represented in the story, and nervous about how they would be received by an audience that does not necessarily understand the weight this story carries for a lot of South Asian people. After I did watch the play, I felt awestruck by how authentically the story was told. I was able to destress from a pretty trying week as I saw my culture represented in such a positive light. I was so happy and impressed with how Professor Tazewell was able to incorporate Indian traditions into the play and how well the cast pronounced the Hindi/Sanskrit words.

I enjoyed hearing a story intertwined with Hinduism and my childhood, and even more, being respected by Professor Tazewell and the cast of Battlefield, and I hoped that others at this P.W.I. would have also appreciated hearing this story told on the mainstage at Kenyon. However, through the grapevine (which is very small at my small college), I heard that this is not necessarily what people expected from this play. Beyond that, it felt like this play, the story, and the lessons it told were not heard or appreciated by many people at Kenyon. Kenyon, where a lot of white voices and stories are told, had a real chance to show up and listen to a story from a new voice not predominantly featured in media and arts. Instead of supporting the storytelling of cultures and people that have been suppressed, students felt that this story was not “interesting” enough to be told. This not only hurt, but made me realize how horribly difficult it is for stories of South Asian Americans to be told, and the chances we do get to tell our stories are not supported by a culture rooted in suppressing people and their history.

This is why Professor Tazewell’s director’s note on why he decided to direct this play really stayed with me. Being Indian-American, it has been rare to see representation in mainstream movies and T.V. shows—forget other art mediums like books or theater—and the representation I do find is often inaccurate and stereotypical. A lot of this stems from the unwillingness of white audiences to hear stories that are not a part of their immediate worldview. In fact, in his director’s note Tazewell wrote, “shar[ing] stories from cultures aligned with the dominant phenotype, we will inevitably produce Euro-centric plays [at a P.W.I. like Kenyon College].” I also decided to reach out to Professor Tazewell to hear more of his thoughts about why he chose to direct Battlefield, as well as the process of bringing it to Bolton Theatre and making it authentic. Written below is my interview with Professor Tazewell. His answers reaffirmed my belief that it is critical to listen and appreciate stories from other cultures, especially when Western voices and white stories have been predominant in your life.

1. Why did you choose Battlefield?

Tazewell: I have been fascinated by the Mahabharata story for many years and have thought about how I might direct a version of the play here at Kenyon. I also discussed this possibility with Professor Wendy Singer, whose specialty is the History of India, many times. In 2004, I did another play, The Conference of the Birds, an epic Sufi story that was adapted by Peter Brook, the same theater director who adapted this play. In doing that play, I discovered my love for the theatrical style of storytelling we used in this production.

2. What was the rehearsal process like and what was the hardest part about working on the show?

T: I enjoy working in a very collaborative rehearsal process. I trust my actors, designers, and production staff to offer interesting ideas that will contribute to the production. For most of my cast, this was their first Bolton Theatre production with KCDC, and for some it was their first play at Kenyon. It took a little while to develop the trust and rapport with the students so that they felt comfortable and confident in sharing ideas and committing to the vision of the play, but after working together for a while, everyone began to share their creativity and talents to the production.

3. What is your favorite memory from this process or did you learn anything new about Indian culture from bringing this play to the Bolton stage?

T: I always do lots of research about any play I am working on. I read a lot about the Mahabharata and Kurukshetra war before and during this rehearsal process. Even so, I learned so much from the play itself and from some of the students involved in the production, especially those who come from an Indian background. This play is also about living with loss and finding our meaning and responsibility to others. I recently lost my brother, who died about a year ago. Working on the play helped me think about how to let go of death and sadness.

4. What was the process of making this play authentic and showing appreciation through the traditions shown, the pronunciations, etc.?

T: From the beginning I wanted everyone involved to be committed to being authentic and respectful of the traditions and culture of India and Hinduism. Obviously, we are not all from that tradition, but we can approach the story with reverence, and do our best to speak the truth that this great story shares with the world. We know we can’t achieve perfection, but we worked with some people who had more experience and expertise in pronunciation and cultural practices, including one member of our cast and her mother, to make sure we were doing our best to have correct pronunciations, gestures, symbolic colors, music, chants, etc. One of the most exciting and interesting aspects of doing a show like this is learning more about these great stories and doing our best to bring them honor and respect and to share them with the Kenyon community. And for me, as a person of color who has spent much of my life in a predominantly white institution, bringing stories to Kenyon from other traditions, including my own African American cultural tradition, is very important.

I want to thank Professor Tazewell for his wonderful and vulnerable answers and hope his work and words beyond the stage incentivize people, especially at Kenyon, to make an effort to connect with stories from other cultures representative of people beyond the White American voices that are so prevalent. I cannot wait to see the stories Professor Tazewell tells next of cultures and traditions unfamiliar to Kenyon, which can be a stepping stone in breaking Kenyon out of its bubble.