Finally, a breakthrough in over five years of UCU strike action

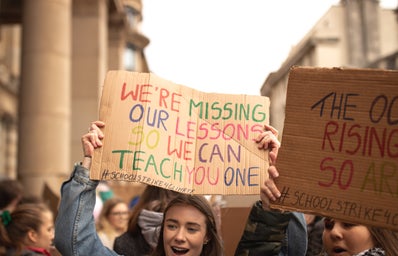

Although UCU have repeatedly stressed that they ‘want to make it absolutely clear that this is simply a pause’, the decision to pause ‘the biggest strike action in the history of higher education’ with over 70,000 university staff across the UK participating nonetheless symbolises promising steps in the fight against casualisation of teaching contracts, pension cuts and equality pay gaps.

The UK has seen this past year and will continue to see labour and industrial strike action across all sectors (rail workers, nurses, teachers, university staff, firefighters and ambulance workers) as the cost-of-living crisis has fuelled ongoing grievances with the government. The news from UCU that commitments from employers have been ‘secured’ will certainly be a breath of fresh air for students at the University of Leeds, who were informed last month that they were set to miss more than forty per cent of scheduled teaching during the proposed eighteen days of industrial action over February and March.

As a fourth-year undergraduate preparing to graduate this year, I myself have been witness to the arguments taking place across UK campuses, which promote or protest against university strikes and their overall effectiveness. Having started in September 2019, I can fully appreciate the frustration amongst students that their university education and experience has been impacted not only by the coronavirus pandemic but also by frequent UCU strike action. I know all too well the bewilderment as we ask ourselves where our annual tuition fees of £9,250 are going, since they are evidently not ending up in our lecturers’ pockets. The sinking feeling when strike dates are announced and tutors are not available to respond to burning essay or exam questions. The sense of confusion and uncertainty surrounding the impact on marking or exam content. However, while this resentment amongst students is entirely valid, as an Arts and Humanities student who has been supported by tutors dedicated to their students’ well-being and has observed the ways in which this field has been undermined, I am of the opinion that the anger at this disruption has to be projected towards vice-chancellors.

Believe me, I am not saying that the dispute over COVID and online learning should not be incorporated into the discourse on strikes by students; in fact, rather the opposite. Starting my second year relying on online learning and some questionable attempts at teaching – such as the live lectures which were never recorded in one module, making it less accessible for chronically ill students like myself – left me frustrated at teaching staff and the university sector. I couldn’t comprehend that I was paying £9,250 for this. This is a conversation that needs to be had. The impact of the pandemic and its poor handling by UK universities, as well as the government’s outright neglect, is a prevalent source of disenchantment amongst older students. What we must remember, however, is that both our issues and demands are interlinked: lecturers’ insecure working conditions are our learning conditions. We are both affected by skyrocketing rent prices, inflation and instability during this turbulent cost-of-living crisis.

According to UCU, the UK university sector generated £41.1bn in 2021, and yet our teaching staff are still asking for reasonable adjustments to be made. Can asking for job security in the face of insecure, zero hour contracts really be criticised? Surely, we as students holding our universities and government accountable for the student rent crisis and loan debt should be standing in solidarity with our university staff. After all, we are well aware that academia is not cheap. It comes at a mental and financial cost. It’s taxing, and therefore relies on hard-working and committed individuals, because progressing through undergraduate, postgraduate and PhD levels gets costlier as tuition fees rise and means of support falls.

From the academics I have spoken to who are striking, there is a genuine sense of disappointment and upset that they cannot be in seminars or lecture halls sharing their research with students, and engaging in meaningful academic discussion in which they get to hear their students’ insight on the week’s topic. Instead, they are outside in the cold, burnt out on the picket lines begging their university to make their employment secure, such as those on fixed term contracts who are perpetually unsure of their employment status.

The industrial strike action has undoubtedly been a large source of chaos and disruption in our lives, and questions could be raised as to whether the UCU’s methods are effective. But that’s the point of strikes and protests. They’re not supposed to be nice. Industrial action is a risk as strikers will not receive pay and are left in a realm of uncertainty, but the right to strike and join trade unions are vital in the workplace. Strike action grabs attention, and makes a firm stance that workers can no longer be pushed around. It is a democratic right. There is a long road to go, but these ‘intensive negotiations’ between UCU and employers signify an opportunity for change. Certainly, there has been some genuine progress that has been made this month: employers have committed to end the use of involuntary zero hours contracts, improve pension benefits and remodel the pay system. But the cynic within me is still concerned that the university sector has not comprehended the systemic change that must occur to protect its students and teaching staff.As a History student specialising in German and Eastern European modern history, let me be clear: the day we lose trade unions and workplace protection is a very grave day indeed.

Written by: Amelia Craik

Edited by: Uta Tsukada-Bright