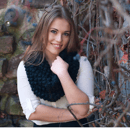

Upon first glance, Dr. Shweta Singh is a bubbly, young professor with an infectious laugh. A closer look reveals that she is also a brilliant, insightful and caring academic professional who’s life and research has taken her across the world and back. Dr. Singh has dedicated her life toward searching for quiet strength in unexpected places.

After earning her BA from Isabella Thoburn College in Lucknow, India, Dr. Singh garnered her Masters in Social Work from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai. Then, at just 22 years old, she moved to the United States in order to achieve her Doctorate in Social Work from the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

She has worked on topics covering women’s identity, education, outcomes of work and health and migration, and social development (to name a few). When she’s not busy teaching at Loyola University Chicago, she has published articles, audio work, and film documentaries on a variety of issues facing women across the world.

We sat down to discuss how she got started in her work, as well as where the journey has brought her.

Dr. Singh approached each question with kindness and raw honesty, interwoven with good-natured self-teasing. It was very quickly apparent that she embodied the full-circle-woman that feminist author, Diane Mariechild, wrote about when she said, “Within her is the power to create, nurture and transform.”

Photo courtesy of: https://www.luc.edu/socialwork/aboutus/facultystaff/singhshweta.shtml

SK: When you were getting your first degree — your BA — did you know that you wanted to pursue a career in social work and feminism? Why did you chose the path you did?

SS: No, I didn’t know. Because we grew up very feminist without realizing it. For us it was a norm, but we knew that we were the exception in our community. It seems that life leads you wherever, but I did my social work by default. I was interested in human resources, and after my bachelors I was pretty sure I wanted to do management. But my masters institute was so highly recommended, and then I went there and I loved the place. So it was like “okay.” And then during that process I realized I wanted to do something with communication.

When I came here and did my PhD at Chapel Hill is when I didn’t know what they were saying about South Asian women, which was very irritating. Then I started digging into that literature because the work I was doing with UNICEF, when I was in India after my masters…there was some contradictions in what they were saying, but I wasn’t able to frame it. I was 22 years old. Like yeah, something’s not right here, but I wasn’t well-read enough to say what it was, it just didn’t make sense. But here, doing the PhD program, you know you read all this stuff.

And Chapel Hill had good teachers. But my masters teachers were amazing. What they taught us was like beyond — I think that’s when I actually, not in my PhD, but in my masters, is when I realized that the world was bigger than the books I had been reading. I realized that I wanted to come up with something that would explain the life that I am interested in. It was a very narrow group. So that’s when I started doing women-oriented work. It took me almost till the last few years to start calling it feminism or post-structuralist feminism and grasping what it truly is.

SK: Some of your current research projects focus on women’s identity, migration and health, women’s identity in media, and school and identity development. What motivates you to do this work?

SS: You know, I want to say that it is some kind of a calling. I think all calling is based on people around you. See that picture over there? That’s all the women that I know and grew up with. I think that’s where it comes from. When you realize that they had so much strength, and all along, unexplainable strength. People call it resilience here — resilience means that you are constantly facing adversity. But facing adversity is only when you realize it’s adversity. Most of us go through different experiences without realizing it was a challenge. You’ll come out of a bad relationship, but for a long time you don’t think it’s a bad one…you just come out of a relationship.

So that, I think, was my motivation, cause I could see all of the women were so strong. It was kind of a contradiction! My dad presented this whole things as how women are being badly treated — don’t be one of those women. I took that in, but at the same time the women around me weren’t being badly treated. They were able to make sure that they were being treated well and at the same time build the same kind of environment for the women around them. None of them are professionals, social workers, or whatever and I think that’s more motivating. The more I researched, the more I met women like that. That became a motivation: to find that strength that is difficult to define.

I don’t like the labeling that goes around in academia. I would claim I’m a post-structuralist and any post-structuralist would tell you this, that I think anything can look different depending on where you’re standing. And people in academia hate that. What does it mean? Does it mean you can’t stand for anything? No, it just means you must allow room for someone else’s perspective no matter how strongly you believe in whatever the hell it is that you do believe. And that is, I think, true education and true humanity. That’s what I applied to the women thing too.

When I realized that my academic work was not going to reach the women that supposedly I was writing for is when I started doing the radio show at Loyola because I was like, “I need to say this. At least in a way that someone will hear.” And then I wanted to interview all these women who had done all this cool work. There’s so many women who are doing such cool work and that continues to motivate me. That’s why all this stuff and all of these books I have to read! True motivation never lets you know that it’s motivating you. It’s so deep inside that at some point you realize there’s nothing else you can do. This is what you do.

SK: It sounds like the strength point you were talking about earlier, where it’s hard to define and tangibly look at.

SS: Yeah, that’s what it is. I used to walk into my global feminism class and say, “You signed up for a feminism class and a non-feminist is going to teach it. Is that cool with you?” Over the years I see how the students have transitioned. The initial students would react to that and it would be like I was calling them out. And it was a good start and made for a good class. But people are not used to being antagonized to learn. The discipline we came from, at my masters program, that was our calling! They were brutal to us! And I’m so glad, because I think that post-structuralism that I’m claiming to be a part of, that is the hidden part of strength.

I didn’t even realize what privilege meant until I went to my masters and I said, “Oh shucks.” And then I came here and suddenly became under-privileged! Now though, the class I’m teaching this semester, they know this argument already! They’re ready to push it forward. But in the last seven to eight years that I’ve been teaching that course, that itself for me is an eye-opening experience that people are becoming more aware of complexity.

SK: I’m impressed with the array of topics you focus on and the complexity within them. We can talk about complexity within the topic of feminism or privilege or subdivide it down from there, but each of the topics that you research and work on are all so different in different ways. How do you balance and chose what you focus on, with such a broad array of topics?

SS: You know this is reminding me of the conversation I had with my brother this morning! One, I don’t actually understand how my brain works. I’m grateful for that! [laughs] I’ll tell you who gave me the best piece of advice about my work. I was seeing an astrologer and I was saying, “I need to do this and I need to do this and blah, tell me what to do!” He was giving me a spiel about how amazing I was going to be and I was like, “Yeah, this is why I came.”

Then I said, “Do you think I can just focus on one thing? Maybe I’m scattered, maybe people are right.” And do you know what he said? He said, “When you’re praying, it’s not like you just have one way to pray, right? You sit down, someday’s you kneel down, you join your hands and in the Hinduism thing you light a candle, you light a lamp, you have books to read. And you do all of that, but still you’re just praying. So if someone sees you do this and this and this and says, ‘Oh why are you lighting the lamp? Why are you lighting the incense?’ there’s a simple response. That’s the process and that’s your objective.” He said that if I did any one of those things less, I’m doing an incomplete ritual. There might be someone who might just be happy by closing their eyes somewhere far away from an actual image from a god and that’s prayer too. That’s their prayer and this is mine. He told me how that’s a calling.

Every little piece I was doing was just about this group of women who were waiting for my work to be done so that their lives could be better. And after that I never questioned my intent of why I’m doing all that I am.

I did start prioritizing more. For example, I was working on this manuscript that was taking forever. And then one day I thought, tomorrow if I stopped doing everything what is the one thing I wanted to look back at and say, “I did this.” And it was that manuscript. So I stopped doing everything for three months this summer. I didn’t go home. I just finished it. That’s what my brother was arguing, saying, “Who does this? Did you plot? Did you draw a character?” I said “I don’t know. It comes easy to me!” He said, “Yeah, I’ve seen your lame kind of writing. This is not The New Yorker.” [laughs] I was like, “Okay, that’s true. But the people who read told me that this is what they want to read. They don’t want to have to spend time trying to figure out sentence construction before understanding what is being said.” And I said that for me, that’s good enough. If three different people from three different segments say that they got it and that they loved it, that’s enough for me. So that’s, I think, my approach to all of these projects.

I think there is a common thread tying them. For example, women in work — I used to call it women in work and women in education, but I realized it is ultimately women in work. Because, you know, your schooling is also. People are not going to school to broaden horizons. Not even returning students. They’re doing it because they want something out of it in measurable terms. And I get it! Everyone must have a good standard of living and it makes life much more pleasant and easier to experience. That, I think, has become more of my intervention area.

But when I started doing women in work, I started realizing that some of the messages and quotes that were coming into me on LinkedIn or random emails from people I don’t know from Greece. I thought my work was in South Asia, but then I realized it isn’t. The minute I say “women in work,” there are too many commonalities there for me. Now I own that and say that yes, I work with women in work and I’m happy to tell you how work and spirituality works, work and leadership works, work and measurable outcomes work, and then tying together.

But until that astrologist talked to me, I really was….you know you take other people’s input and it does affect you! Most of the work, I think now, especially, is geared toward that. I turn down anything that is not about this because just knowing that I can do it, I think that phase is gone. There was a time when I thought, “Oh, can I do this? It’s so challenging! Yes, I would love to do it!” [laughs] You know? That phase came and went.

SK: I wanted to talk about your documentary on women’s issues in India, Confounding Traditions of Modernity, Urban Indian Womanhood…could you explain the film a little bit, and why you felt you needed to make it?

SS: A bunch of my friends in India, who I knew from childhood but was not in touch with for the last twenty years, they were all struggling a little bit. And I thought that their struggle didn’t have reaffirmation of how strong they were. The generation that had inspired me of my parents and my aunties and my cousins…they didn’t need that reaffirmation. So I realized that there must have been a deficit in the time that I was away, doing my thing, and that deficit needed to be filled by showing what it means to be empowered.

Those people, and their stories, I just wanted to show them how they come across. They don’t come across as, “I failed and I’m struggling.” They come across as everyday they are winning a little. And I’d much rather that people saw that message. So when I screened that documentary here at Loyola, actually a couple of people who were senior academics got kind of annoyed. They said, “Who are these women? Women are not like this. Are you going to pretend there’s no rape and dowry and violence?” I was like, “No. But I’m also not going to pretend that in spite of all that women are still coming out on top.” I would much rather tell them, “Look, this is how you’ve come out on top,” than tell them, “You know what, you could be one of the statistic.” This is not a story of victims.

SK: Yeah, you see that a lot in academics where people sit from far away and preach about the victims in a different country.

SS: I’ve written this piece on the MeToo movement in India. I had to modify it a little bit because the people I’m trying to get it published with are annoyed. [laughs] But, basically I was saying that for a long time, we heard this whole ‘global south stuff’ and what is that? The entire community of women is victims? How do you think they survive, they don’t have a 9-1-1 to call! You know? Who are they counting on? They’re counting on their families. Don’t walk in there and say “global sisterhood” because global sisterhood is not going to come and walk them home at 11pm when they’re afraid to go out. Heck yeah there’s no one out there who is going to come! There is no system! It’s taking time to build those things!

I said, actually, it’s not MeToo but YouToo, sister. Because look at it. In academic circles we know that there is violence and domestic violence and street violence. We know that. But the common perception of the Western World is very enabled and empowered women. And these last few years have been an eye-opening experience for many women. It shouldn’t have been. It shouldn’t have been an eye-opening moment. When Meryl Streep came up, I was like, “Really?!” [laughs] I had written that the global south could now turn around and say YouToo. Own that now! You’ve gone around saying, “Hey victim.” Now it’s time to say, “Hey yeah, I’m a victim. And I’m sorry that I pretended that it was just you.” This is a moment of saying YouToo and then saying MeToo.

I do take affront with people who are academics and who are— that’s your job. You get to read, reflect, write, and then double check you theory and modify it. For years and years, to not modify your theories, and then say maybe this doesn’t explain gender theories and relations, this might not explain the gender construct…we might need all these little elements to deconstruct and reconstruct what this reality is and then say that we constructed this reality of an empowered womanhood. And there’s an obvious disbalance.

There are so many studies that talk about double-shift. It was true in the 60s and 70s of European lives and US lives of women who were doing more. They had just found jobs and were still balancing. But this is 2018. Women are still doing more and will continue to do more. You know why? Because women prioritize families and they prioritize children and they prioritize caregiving. Women prioritize relationships. Own it. Now, instead of saying, “Don’t do more!” or “Why don’t you have men do it?” Why don’t we teach men to value relationships? We don’t do that! We ask women why they are valuing relationships!

That’s the whole complication with women in work. Don’t be relational while you’re a boss. Now you’re talking about cooperation and collaboration and nothing is more cooperative than a woman. She has to pull so many small pieces together, and especially if you don’t have resources, trying to make the system work. I feel like some of that doesn’t come across if you’re just talking about it.

But when you see the documentary you see the way a woman is dressed and then you hear that conversation and that’s how you realize how complex life is. Completely traditionally dressed women, owning that womanhood, are talking about they went and saved a woman from being beaten by her husband and got her a divorce. That was my main motivation, that it’s not as simple as it looks. Someone else’s life is always more complex. It doesn’t matter how we reduce it or aggregate it out. Most of my research is about trying to break down myths.

SK: It feels sometimes that labeling people as victims perpetuates that cycle instead of helping anything. It makes it almost worse.

SS: It takes away the feeling of, “Oh, I got it!” Suppose you have a meltdown in front of someone and a month later they ask you if you remember and if those people are still a problem. Then they keep making it a reference point every time you two meet and when they describe you to other people they bring up your meltdown. That is not an enabler.

I think it’s the same thing in literature. Every paper I pick up, every story I read, of street violence happening makes me think, “Where is it not happening?” Any extreme, I feel especially for women, is a mistake. Because women are the ones who end up carrying whatever culture is being enforced. It doesn’t matter if it’s a culture of ‘be independent’ or if it’s a culture of dependency. It takes away that element of choice.

And the women in the documentary — some of them I really knew well. They were friends when I was a kid. They themselves have kind of changed their story a little bit. Those ten years may have been very hard on them, as the kids were little and they were dependent on their husbands. But now that the kids are grown they feel more independent. In the last couple of times I’ve spoken with them, they’re on a different planet! They’re like, “I don’t care about whatever.” It’s inconsequential in their lives. Where is the piece that talks about how women are empowered at different age groups? It’s not there. It’s missing, you have to look through even the top ranked journals. What women experience changes depending on all these demographic variables.

SK: With that, what are some contrasts/connections you have found between global feminism and your work with the women in India?

SS: One of the mistakes I have done is that I’ve never presented a paper at a women’s studies conference in India. There was once that I was going to but I missed my flight. [laughs]

Independent thinking takes a lot of guts to articulate. It’s not that people don’t think differently, but they don’t want to own it. I think, unfortunately, academia in India — especially women-centric academia — wants to be very radical. They don’t want to be part of European Feminism or Western Feminism. Indigenous feminism is where we should find the similarities and differences. The underlying complexity of thinking, the underlying complexity of conceptualization, deciding what the measurement of those markers is going to be — all of that, I think is a commonality. But other than that, I feel it is a very contrived similarity.

Even global feminism…it should be global feminisms. Like, where is the unity? We’re talking about a multiverse at this point, which we should have talked about always! But that kind of freedom of articulating— there are some people around who we are more comfortable saying things to because we know they have more of an exposure to the world systems. What is exposure of academia in any country? Most of the stuff is being published here. Most of these books were written by people here. Here meaning European countries. So it’s people writing from Nordic countries or people writing from America or people writing from Britain. What are the odds that it’s going to reflect everyone? How difficult is that and why should it take 40 years to say that? In academia?

I’m okay with people on the street saying it because they are not being paid to read and write and reflect. But if this is what you do for a full-time living, then I don’t know. So I’m not sure if there are no commonalities, I think belief in women’s rights is universal at this point. It’s one of the values that people will always hang their coats on because it’s got a currency.

But similarly, it should be for a number of other things. There are a bunch of women who want to have children and it’s okay for women to not have children. Either group sitting in judgement is what is wrong with academia in the feminist sense. They are not open to the relativism of thinking. If you’re not going to think about a particular group — especially a marginalized, disenfranchised group — don’t walk into their space with already an idea of what their identity is about. That is, I think, more grievous of an insult than saying someone is not a feminist.

SK: When we think of academia, we tend to think of it as some of the most understanding groups — from the outside looking in. But what are some challenges that you’ve still encountered within that world, as a woman?

SS: That’s an interesting question. I do appreciate that I have one big advantage, which I owe to my father. We were taught to fight for our positions very early on. We had no disciplining except for an auntie who was very free with her hands. [laughs] You know, she’s adorable, but yeah. We were raised in a very intellectual tradition for girls and for individuals anyways. Our only rule was that if we could argue something was the right thing to do…do it. If you mess up, it’s your problem. So very early on we learned to defend our positions. A ten year old prepared to defend her position is a big advantage and as you grow older it just becomes a core value of who you are.

So I do realize when I walk into meetings, that within two minutes my generalized disrespect for the status quo conveys itself to most people and that’s the first thing that people notice. I think that maybe it reduces a little bit of what I would have experienced, but it doesn’t take it away entirely.

When people can’t get in through the straight route of communication, then they will use the passive or minor aggressions. I do experience that often, but you know not where I would expect. When I studied at Chapel Hill, I was okay with walking into a couple of stores and those people had never actually met someone who would fluently speak with them in English. That’s unfortunate because there was a whole hub of IT right there that was populated by South Asians. But I guess those people didn’t go to those types of stores, whatever. I was still okay with it because I knew what I was when I was back home. If we saw someone, like a foreigner, we’d be like, “Oh did you see that?” We have to own it! That’s how it works, I mean what’s the big deal? He’s not getting a PhD — I am. And if I’m that invested in him having the right approach in talking to me, I will sit down and try to have this conversation.

But when I’m hanging out with a group of people who are academics, who should know more? They are making those statements with absolute contempt and ignorance. Ignorance is basically being contemptuous of everything you have not experienced. Like I said, academics must hold themselves to a higher standard. If you’re going to meet with someone who doesn’t look like you, talk like you, doesn’t come from where you come from, that’s also your responsibility. If you don’t know, find out. I’m not interested in being your explanation for why, “Oh, do not all the women suffer from dowry and arranged marriages?” Arranged marriage is not a suffering. Otherwise there would not be Tinder, there wouldn’t be Match.com, there wouldn’t be Chemistry.com — that’s an arranged marriage.

So what about when I have had examples of people who have made really foolish statements? Earlier I was presumptuous and not kind. Kindness is something that I think grows on you as you age. Now I’m less judgmental. Depending on where I think they fall on the cusp of intelligence, I do modify what I’m going to say so that the next person they meet up with who is a woman or something of the gender binary, gender continuum, or different, they will know that these are the things you can say. I have experienced it more with people I wouldn’t expect to experience it from.

My perception is also different. If you’ve not been exposed to someone or something, I do not expect you to know. When I walk down the street, once in a while — in Chicago that’s pretty rare, it’s such a global city — if someone says something where I get it…honestly it doesn’t bother me because I’m like, “I don’t know how I would feel if I was in the same position where I saw that someone who doesn’t seem to belong here on the face of it seems to have more privilege than me.” It would bother me, I’m positive it would. So I want to accommodate that, versus if I walk into a room and hear, “How come you don’t have an accent?” I say that I do, you just have to listen very closely.

SK: You made a good point where people don’t have to be gatekeepers of intelligence for other people when you have the tools to research it on your own.

SS: Yeah! Especially now! When I don’t know something I really feel like I should immediately apologize, which I end up doing. I’m like, “I’m sorry, I have no clue!” People apologize to me for not being able to say my name and I’m like, “How many Shweta’s do you know?” I know a million Julie’s, I know a million Linda’s. If I’m not able to say a name right, I ask the person if they would rather I call them by their last name or if it is okay. But I don’t want you to keep apologizing and making you feel alienated because you keep messing up my name. Honey, my name is not going to change just because you can’t pronounce it — we’re barely going to meet again! [laughs]

SK: You get the extremes again of either ignorance or over-apologizing.

SS: And I do feel that a lot of it is intentional through these micro-aggressions. I’ve had a couple of times of people saying things they shouldn’t have said where they say, “Oh, I’m sorry I think I confused you with the other Indian girl.” If you did confuse us and if you thought it was okay for you to say it, as far as I’m concerned, you need to continue to say it so that people know who you are and know where you’re coming from.

With the students, I want them to know what this looks like and what this feels like. I had a question on gender where I asked them if they thought the gender construct could be accommodated better in the non-profit leadership world. And there was an interesting write up from Forbes that I gave them as context for the question. Actually a few of the students wrote in and said, “I don’t see why a woman has to be a woman to be a better leader? I don’t think that’s a criteria.” And then some were like, “Yeah, a woman should a woman, why should she be anything else?” Like, see? Being on a gender continuum doesn’t determine what kind of a leader you will be or what kind of a mother you will be. You choose a gender continuum and you choose what kind of worker you’re going to be. There’s a whole range in almost all social constructs.

SK: At a university with a significantly larger female population, what does it mean to you, that you get to be in this position and be a role model and a mentor for young professionals?

SS: It really means a lot. For a while now I’ve tried to somehow get engaged more with the students — especially women. I’m just going to own it, all my work is kind of women-centric. Even the gender continuum, I’m not going to pretend I know much about LGBTQ or the other different identities that overlap with the gender continuum. But girlhood and womanhood — those experiences I really think, reading, writing, reflecting, and performing at different levels, I feel like I wish I had known someone who could have talked to me and explained these things to me because I have a lot of nieces and cousins. I did try, very intentionally, to make that difference in their lives.

It’s really important for women to know that the choices you make right now — where you study, where you’ll go with this — is ultimately going to be the kind of lifestyle you have. There are no if’s or but’s. If you choose X, Y happens. You know, it was Ayn Rand who said that the question has never been who will let me, but who’s going to stop me. That’s how women think now and women are able to put themselves out there. The man though…that’s a rarity. I haven’t met many men who are naturally able to just give and put someone else forward. To women it comes, I think, much more naturally. Friends will pull their friends forward, mothers will pull their daughters forward. I think women are naturally enablers and I don’t think men are. It’s not a judgement call, it’s just whatever it is. I want to be very intentional and tell women that you need to be able to own this. If you’re going to do this you need to own this.

SK: Do you think you can pinpoint something that’s been your greatest achievement within your career so far?

SS: I can pinpoint what I would like to happen. [laughs] I don’t think I’m there yet. Just being able to own all of me, I would say is plenty. Everyone goes through those phases of letting…what is that phrase? Don’t let anyone take your power. I think I’m finally in a position where I might let them take it for a few minutes, but then I got it. Earlier it would be sometimes, you know, you let people question you and it becomes a statement on everything you ever did. So I don’t think so.

I think my greatest achievement is yet to be because there’s too much stuff. One of the drawbacks of multi-tasking, as my brother and I discussed, is when you’re praying in a very elaborate ritual, and you’re trying to figure out what you’re praying for. First you get the idea of who you’re praying to and it takes a full circle. It’s a complex ritual. At some point I will be done with it and at some point I will have offered my complete prayer, but right now it’s still in the making. I don’t think the prayer is complete yet.

SK: Have you had anything, you think, you have failed at? That you have learned from?

SS: Oh, so much. You know the whole thing about planning and processing? Not doing that and instead doing very instinctive movements has a downside. I tend to do things before I think about them and I feel like if I had optimized that process I wouldn’t have failed at a number of things that I did fail at.

One year I wrote eleven papers and ten got rejected. One got published. And then, that one paper…some people who read it were like, “This is the best thing I have ever read.” Some of the students said that. I wrote that one in two days and the other ten took forever! And the feedback I got from feminist journals was, “This isn’t feminist enough,” or “There’s too much culture in this,” blah blah. Those failures are little, little, little, and there’s so many. But when you’re in your dark space and you’re just looking at that it looks so much closer.

I really think it’s not worth it to not think of a failure and I really like that piece that says while you’re trying,

you’re not failing at anything. But yeah, I’ve failed at a bunch. A bunch of things. But, it’s okay.

SK: To look back at what you haven’t done, or perhaps have done, always gets me to see that it all brought you to where you are right now in this moment.

SS: You’re just in this moment. Always, it’s just this moment. If you’re going somewhere, you’ll reach there. It’s just the path is your choice. The path is always your choice. I don’t think anyone can change that destination. Where you’re going you will reach. But the pathway is your choices and ultimately it’s your attitude that will determine if that pathway is going to make you happily or you’ll go there grumpy and upset. You might as well just be happy about it. [laughs] What can you do?

I think the confidence also comes from the belief that if you have that little circle of people around you that are able to reaffirm whenever your own faith falters a little bit — which it will, as it’d be silly to presume that every day is going to be a Sunday — it helps if those people are around. For me, my universe has always been my family. And you pick! It doesn’t matter who you pick, so long as it’s there. That is really important and it’s a blessing because not everyone has that. Not everyone has people that they can fall back on. What a huge deficit is that for little children who grow into adults! Questioning who they are and who they can be and someone not believing in them! I think that’s terrible. Life is so complex. It’s best to pick your little corner and own it.