Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata started Studio Ghibli along with producer Toshio Suzuki in 1985. Both then started directing their separate films under the banner head of ‘STUDIO GHIBLI.’

There is an intriguing difference between the films of Takahata and Miyazaki. Although similar themes, their films vary in their outlooks. One can observe the differences (and similarities) in their exploration of the themes: WAR, GOD, YOUTH, BEAUTY, and SEASONS.

WAR

“War profiteers are villains and bounty hunters are just plain stupid” – Porco Rosso

War forms the backdrop of several Ghibli movies. Both Miyazaki and Takahata are against war and are ashamed of Japan’s imperial past. Here, is a distinction between their illustrations of this.

In Grave of the Fireflies, Takahata showed the gross realities and extremities of war through the estrangement of children from their family and society; further, from the actual truth. He draws attention to the plight of the young souls who had to fend for themselves in a cruel world of war.

Miyazaki, in The Wind Rises, portrayed the relationship between the artist and his art. That is the engineer and his plane and the tragedy of his ignorance of the real world.

Porco Rosso is similar in dealing with the relationship between a pilot and his plane. Marco is a cynical war veteran with survivor syndrome. His disenchantment towards life makes him ignorant of the people who care about him.

Miyazaki is passive in his commentary about war. He depicts the exploitation of skilled professionals in battle and how governments use their art as a weapon of destruction.

Princess Mononoke is about the war between nature and humans. Miyazaki spotlighted the human ignorance towards nature and San’s (a human child who’s raised by wolves) ignorance towards her kind—giving closure on how compromise is the only solution to the war.

While Takahata’s Pom Poko too, is about nature’s war with industrial development, it is about several animals such as raccoons and foxes. It is about their fight to retrieve their lost habitat. This movie concentrates on the inevitable erasure of animals’ habitat at the present rate of development. Pom Poko’s raccoons also represent the repressed and helpless poor. Here, the war is between the different economic classes.

GOD

”The forest spirit gives life and takes it away. Life and death are his alone.” – Princess Mononoke

Miyazaki and Takahata both have spiritual sequences that increase the fantastical imagery in their films.

A scene from Takahata’s Pom Poko:

… The golden procession comes to a halt near the dead raccoons. The almighty Buddha takes them into his embrace as they climb up to the place of all good…

God in Pom Poko lessens the melancholy due to the loss of life. Takahata uses the guise of God to cover up the grim reality in the pretext of something better ahead.

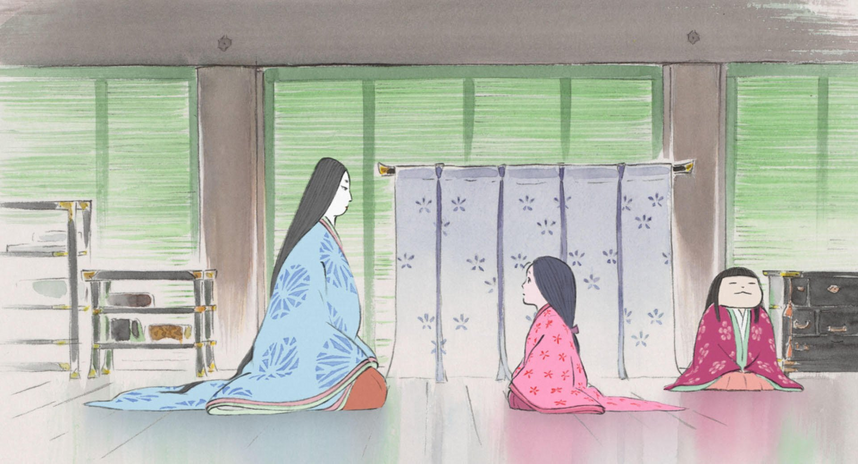

A scene from Takahata’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya

… A procession of celestial beings led by Buddha come to take Kaguya back to the moon owing to her sad life on Earth…

God plays the antagonist in The Tale of Princess Kaguya. God is the reason for the loss of her freedom because he is her controlling parent. He is the death of her emotions; this time, you see the evil in this golden celestial procession as they dance their way to the place of all good. Kaguya, the daughter of God, yearns for a place in the ungodly society.

Takahata makes God a part of life, a fact. His commentary is not about God, the all-knowing and good but about God, the ignorant almighty.

Miyazaki in Princess Mononoke deals with the destruction of God himself. His killing turns God into an all-devouring beast, the devil. In Princess Mononoke, God is Nature.

In Spirited Away, Miyazaki humanises gods and gives them accessible characteristics. He shows their prejudices, their private eccentricities, and their duality in either being helpful or just spectating life. The gods of Spirited Away are bizarre and hypocritical spectators. In this aspect, Miyazaki presents to us very subtle humour.

Miyazaki shows the hypocrisy in God’s nature; this aspect of his portrayal of God is shared by Takahata too.

YOUTH

Most of the protagonists in Studio Ghibli are young. There is no harm in saying that youth is the most prevalent topic in Miyazaki’s and Takahata’s films.

“Such a bad grade in math again.” … “But I got a B in science!” – Only Yesterday

Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle is exceptionally concerned with the theme of youth and age. Characters in this film have different relationships with their age, such as the old witch who makes herself young and turns a young woman old. Her insecurities regarding age intensify her love for the young. The young woman accepts her fate as an older woman and decides to deal with it. In this process, she adapts to a new, foreign environment, and also her now changed reality. This adaptability and acceptance of change make her youthful.

Contrastingly, Howl, a boy going through puberty behaves his age: one who gives focuses on trivial matters and has baffling mood swings. Miyazaki created this complex web of characters who accept, change, act or subvert the roles of age and youth. Through this Miyazaki satires the world’s obsession with age and youth.

Alienation faced by children in moving to a new place is a recurring theme in his movies. Miyazaki’s characters mature in their journeys to overcome alienation. These journeys are the epic adventures that his films are known for. But, subtle, is the fact that the characters attain a level of maturity, grow older and at times even become disillusioned in their search of familiarity and acceptance.

Kiki in Kiki’s Delivery Service loses herself in her insecurities and disillusionment. Chihiro in Spirited Away has to fight against Yubaba to retrieve her parents. Kiki and her both overcome their dire circumstances by being true to themselves.

Miyazaki knows and believes that childhood is a brief period and doesn’t lose any chance to show the joys of it like in My Neighbour Totoro.

Takahata draws upon the denial and(or) the loss of childhood. As a result, children take on the role of adults in his films.

In Grave of the Fireflies, Seita and Setsuko are left to fend for themselves in bomb-stricken Japan after their mother passes away.

In The Tale of Princess Kaguya, Kaguya grows up too fast (literally), she has almost no childhood, getting only a glimpse of freedom before her father wants her to get married.

Only Yesterday is filled with feelings of lost youth and missed childhood opportunities. Taeko remembers her disappointment in her parents who though loving, don’t care about her interests and let her down many times by brushing them off as unnecessary. Isao Takahata beautifies the isolation and estrangement of youth. Takahata comments on the fault of parents in not recognising their child’s wants. He masks nuanced emotions of youth behind his astoundingly beautiful films.

BEAUTY

Beauty is sorrow in both Takahata’s and Miyazaki’s films. It is shallow, unfair, painful and objectifying.

“It’s not really important what colour your dress is. What matters is the heart inside.” – Kiki’s Delivery Service

Their views are similar in their portrayal of it.

A scene from Howl’s Moving Castle:

“What’s the point in living if you aren’t beautiful?” “I HAVE HAD ENOUGH OF YOU! I HAVE NEVER ONCE BEEN BEAUTIFUL!”

Sophie is forced to come to terms with her insecurity of not being conventionally pretty. Though Sophie moves along with a strong façade, this is broken at her realisation that if someone (Howl) so beautiful is dissatisfied with the way they look, then how would she ever be happy with herself? She felt as if his complaints were unfair to her because she looks normal.

The following scene is the one that results in Sophie releasing all her pent-up emotions it was when she was at her most vulnerable. Personally, this is the most potent scene in Howl’s Moving Castle.

This scene also makes one think about Howl’s superficiality and his discredit for others.

Miyazaki shows the pain of not being pretty, in other terms, not constricting to society’s beauty standards.

In Takahata’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya:

“To me, you are a robe of fire-rat fur. Put in the flames, all impurities burn away but, it is not consumed and merely glistens all the brighter. You are as pure as this rare treasure of China”

The following is said by a court counsellor who is one of the suitors who come to make Kaguya their wife. The suitors all compare her to fake treasures, objectifying her and reducing her to just her looks. They want to claim her like a prize.

Takahata focuses on the abominable idea of beauty. Kaguya feels trapped as a princess and is further, violated by her beauty.

In Miyazaki’s Porco Rosso too, Donald proposes to Madame Gina, after seeing her once and thinks she will accept him because of his good looks and talent. But Gina loves the human-pig, Marco. A pig here signifies disillusionment, coming to terms with the injustice and the horror of life.

SEASONS

Miyazaki and Takahata illustrate the real beauty of nature and seasons.

“Nobody understands the weather anymore. Might as well look at shadows and listen to crickets.” – Ponyo

Seasons have their connotations in the duo’s films. Takahata primarily uses it to enhance his storytelling.

“Round, round, go round Go round water wheel Go round and call Mr. Sun Birds, bugs, beasts Grass, trees, flowers Bring Spring and Summer Autumn and winter Go round, come round, come round.” – The Tale of Princess Kaguya

Spring signifies happiness and the blossoming of love. Spring is equated to fluttering hearts and emotions. Spring is the start of something new and exciting.

“In spring, love rivalries and sweet nothings fill the air.” – Pom Poko

Rain brings out the vulnerability. The characters are at their most real, emotionally. Rain comes in moments of sadness and realisation; it also gives way to mysteries. Rain brings people closer.

“Rainy days, cloudy days, sunny days…. which do you like?” “……. cloudy days” – Only Yesterday

Autumn is the time for contemplation; it is like the silence before the storm.

“Joyful laughter breaks the silence of an autumn eve…Basho” – My Neighbours The Yamadas

Winter is a loss of sense of self and emotion; it signifies isolation and barren expanse. Winter is the harshest season for Ghibli characters.

“First Snow! Let’s take a picture!” “Shut the door, it’s cold.” – My Neighbours The Yamadas

WAR, GOD, YOUTH, BEAUTY, AND SEASONS are just the tip of an iceberg in Ghibli films’ backdrop. So many precious gems are illustrated in their movies. Every character in their movies are relatable and has a story of their own. They both share similar views on many things. Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata don’t write about evil and good, they write about people.

But, considering their filmographies, their most contrasting difference is…

REALITY

“If you grow any fatter, they will eat you!” – Spirited Away

Hayao Miyazaki might as well start singing ‘Dreams are my reality, the only kind of real fantasy’ (Reality by Richard Sanderson) for all he cares about it.

In Miyazaki’s films with both original and adapted screenplays, grandeur takes up the front seat. His films feel like a roller coaster ride.

“At work and at play we girls were livelier and more spirited than the guys. It was like we’d finally found our wings. But maybe, we were just flapping them pointlessly.”– Only Yesterday

Isao Takahata’s movies are an imitation of reality. They are nostalgic. Even in a story like The Tale of Princess Kaguya, he concentrates on the mundane realities of her life. He turns these small moments into something heart-wrenching and precious. He creates significant quirks for every character. Be it an older sister who secretly likes an actress in Only Yesterday, the feeling of seeing someone familiar in a railway station in Pom Poko, or even the reluctance of your family members to bring you an umbrella (My Neighbours The Yamadas).

You can relate to everyone in a Takahata film. Takahata is not interested in painting a silver lining. He makes reality hit you flat in the face.

Miyazaki is more friendly. His stories are filled with heartwarming characters. Be it the reserved bakery worker in Kiki’s Delivery Service who packs her Kiki’s lunch, or the radish spirit in Spirited Away who helps her with directions. It also includes how Lady Eboshi in Princess Mononoke helps social outcasts by providing them with employment and a place to live. He doesn’t make us see everything through rose-tinted glasses, but he does elicit a childish joy in us as we see the character go to the depths of an unknown fantastical world.

Thus, the colours of their filmographies are incredibly contrasting.

Takahata’s is melancholy with a feeling of isolation and utter loneliness.

Miyazaki’s is overwhelming and adventurous, filled with larger than life characters and warm fuzzy endings.