Note: This article is the first in a three-part series on anti-racism.

Anti-racism is the latest buzzword we’ve all seen floating around lately. It sounds profound–– and is profound–– but what does it mean?

Let’s take a look at some definitions:

According to NAC International Perspectives: Women and Global Solidarity, anti-racism is “the active process of identifying and eliminating racism by changing systems, organizational structures, policies and practices and attitudes, so that power is redistributed and shared equitably.”

Peggy McIntosh, feminist, anti-racist educator, scholar, and all-around badass expands on the definition, saying: “Anti-racism examines the power imbalances between racialized people and non-racialized/white people. These imbalances play out in the form of unearned privileges that white people benefit from and racialized people do not.”

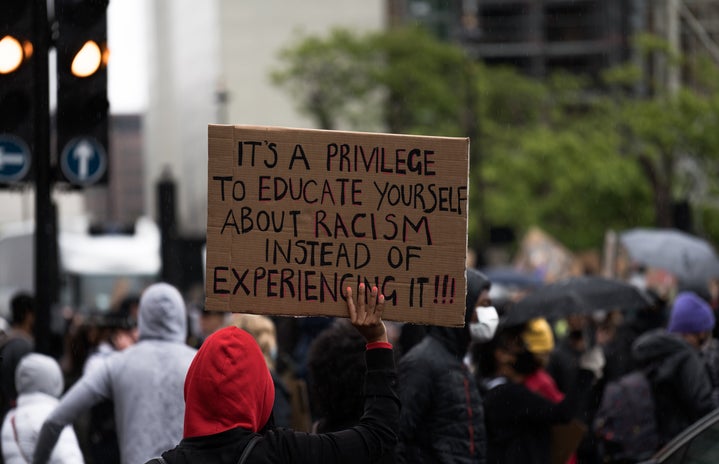

The first definition highlights an integral facet of anti-racism: it is an active process. We can’t merely claim to be anti-racist; we must wake up every day and never stop working towards dismantling racism wherever it persists. We are not anti-racists; we are individuals practicing anti-racism. This statement means confronting our personal biases and the prejudices of our friends and family. It also means reflecting on the media we consume and create. How does white supremacy fuel our work? Our passions? The way we speak? The way we cast judgment?

As you’ve probably gathered, this is by no means easy work. If it was, what would be the point? Anti-racism calls us to never stop working on educating society. It is a daily practice, a journey with no end. It is a perpetual calling to be better and do better that we must answer daily. We won’t wake up one day free of all prejudice; instead, we will practice–– every day–– confronting and eliminating the bias as it appears. This task is a challenging, intimidating undertaking–– but it is also a necessary one.

A look back at McIntosh’s description illuminates another point–– non-white people are inherently racialized in a manner that white people are not. We cannot pretend to live in a “post-racial” society, devoid of any internal or external prejudice; such a community inherently erases people of color. To be anti-racist is to combat the oppressive structures of race in the overtly white supremacist society in which we find ourselves. Any attempt to admit that one harbor no prejudice is 1) not genuine and 2) not enough. Anti-racism is a fight against the implicit structures perpetuating racism, and an effort to dig into the root of the problem and not merely prune its leaves.

Now, I hear you asking: “Well, why the hell haven’t I heard of “anti-racism” before now?”

In his 1975 essay, “The History of Anti-Racism in the United States,” Herbert Aptheker addresses this question. He writes:

“One might wonder whether the absence of a body of literature on anti-racism in the United States is not due to an absence of anti-racism in the country? The evidence is against this view. It shows, on the contrary, that just as slavery induced both its defense and its attack, so racism induced both its defense and its refutation, but the literature presents the former and largely has ignored the latter. It is past time this neglect was overcome” (17).

The reason you haven’t heard of anti-racism?

Systemic racism!

I know, shocking. The white supremacist society in which we live would rather focus on racism than its refutation, to focus on problems rather than solutions. It would rather focus on black and white issues than nuanced discussions and active work. If we focus on racism as an isolated problem, we can attempt to solve it through simply being “not racist.” And, in the words of the always-timely Angela Davis: “In a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist, we must be anti-racist.”

I agree with Aptheker–– it is past time we stop neglecting this problem. And if enough of us are willing to do the work, maybe it will finally be a better place for us and future generations.