As a pre-teen, I devoured the Hunger Games series; the books had me saying “one more chapter” all night long, while the movies had me on the edge of my seat. The trilogy comments on fascism, capitalism, and especially exploitation. It is through the examination of exploitation that the series packs the most punch. Yet, the element that seems to be discussed in volumes disproportionate to its importance in the plot, is the supposed love triangle between Katniss, Peeta, and Gale. I’ll just say it—Gale was never a viable option. But more than that, Suzanne Collins wrote the Hunger Games in a way that criticized the need for teenage romance as a survival tactic, but our media became obsessed with the Gale – Katniss – Peeta love triangle, which shows why the topic was necessary in the book to begin with.

Suzanne Collins got the idea for the series while flipping through channels and going between reality TV and coverage of the Iraq war. The two existed in such contrast and were paired in such an unsettling way that the idea of entertainment as distraction and pacification stuck. She also drew inspiration from the Greek legend of Theseus and the Minotaur. In this myth, King Minos forces Athens to sacrifice seven youths and seven maidens to be hunted by the minotaur in a labyrinth as punishment for past crimes. The crime of sacrificing children as punishment is rendered all the more cruel by reducing their lives to a source of entertainment.

It’s easy to see the connection between this legend and the way the Capitol maintains order throughout Panem. The games are designed to hit two birds with one stone. They instill fear in the districts while simultaneously keeping the Capitol citizens distracted from the realities of the districts and their own dependence on them.

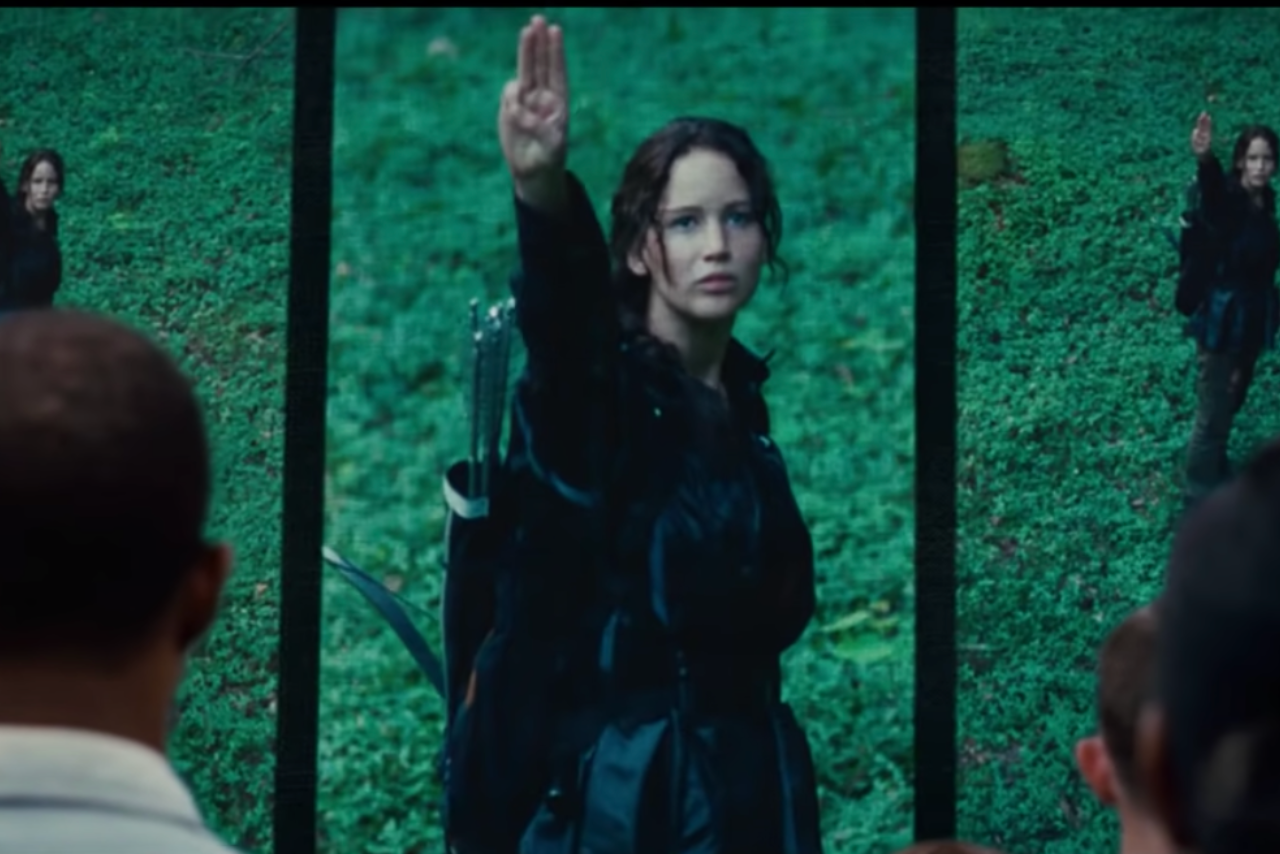

Our story picks up when twelve-year-old Primrose Everdeen is chosen in the lottery to be district twelve’s female tribute. Her being a tiny and gentle girl, she doesn’t stand a chance against 23 other kids, most of whom will be bigger, older and stronger than she is. Katniss knows this is a death sentence for her younger sister, to whom she has essentially been a mother, and volunteers as tribute in her place. From that moment onward, she is no longer a person with agency, but a public figure whose every move fits into the storyline of an intricate game, televised for the entire country’s viewing.

We too are watching this game play out, because we as readers are the Capitol. The typical young adult tropes that get us wrapped up in the story (star-crossed lovers, a love triangle, having a seemingly purely evil antagonist like Cato, a battle royale fight to the death, etc.) are not only a conscious decision on the part of Suzanne Collins, but the characters themselves, who choose to play them up. The subversion of these typical tropes meant to get readers caring about the characters reveals an additional reason for their inclusion. Do we care about Katniss’ reality or do we just want to see the games play out? Are we like the Capitol, in that we need these tropes to care about these kids’ lives?

These tropes are exactly that: tropes. Katniss and Peeta aren’t star-crossed lovers destined to lose each other but instead Peeta chose to play up that angle to get sponsors to care about them. Cato isn’t purely evil, he’s a victim of the system as well, which is made painfully clear to Katniss and Peeta when he reveals to them that all he knows is killing—as it’s what he’d been brought up to do. Cato too was playing an angle to get people to sponsor him. We see Cato as the Capitol does, the ruthless killing machine, and not a boy taught to kill from the time he could hold a spear.

The media at the time of each films’ release played into their role as the Capitol beautifully. So much press coverage tried to create buzz around the Team Gale versus Team Peeta debate as had been done with Twilight. It’s ironic that while the story critiques the exploitation and forcing of romance upon these kids so that people care about their fate, the buzz around the movie was about the love triangle. That’s not to say that that’s all anyone cared about, but there was a lot more coverage on the love triangle relative to its prominence in the story. I guess Katniss, Peeta and Haymitch were right—sometimes people need a cheesy buy-in to end up caring about the characters. Maybe most people ended up caring about the characters as individuals in the end, even if the love-triangle drew them in.

The theme of exploitation is most prevalent through the romance angle and the “chosen one” trope. It’s highly common in young adult dystopian fiction for there to be a teen “chosen one” who will lead the fight against whatever “bad guy” is terrorizing the story. Katniss was not only forced into that role, but that’s all it is—a role for her to play. Even when she is out of the games and with the rebellion, she still has to play up a public persona, albeit a different one, but nonetheless a character that isn’t her. She is a tribute, a victor, and a Mockingjay but is never allowed to be just Katniss. The adults around her, those with agency, consistently manipulate her circumstances to fit their political agenda; the star-cross lovers trope to keep Peeta and Katniss alive was only the beginning.

This ruse snowballs into Catching Fire. To mark another 25 years of the Hungers Games, there will be a special theme to keep the games fresh for the new generation, one that is supposed to be predetermined. This is not the case, a plan is orchestrated to further a cause, though what cause depends on who you ask. President Snow is trying to kill Katniss off in a way that doesn’t make her a martyr, as he needs to show that not even victors can go against his word. For the rebellion, they are playing with the lives of the victors to get Katniss out and make her seem the hero.

There is no “big bad” in this trilogy, but instead a systemic lack of care for human life. Both the rebellion led by Coin and the Capitol led by Snow are willing to play with life like a game. For instance, upon the rebels’ victory (won by killing hundreds of Capitol children) Coin wants to hold a symbolic Hunger Games. It’s not enough to kill Snow, demonstrating to Katniss that the cycle of violence will continue and that the system itself needs to change.

Now you may be asking, what does this engrained lack of care for human life have to do with Gale? Well, Gale has successfully been indoctrinated into a system that doesn’t value life. This is clear from the very beginning when he tries to reassure Katniss by telling her that shooting people is no different than shooting animals. In sharp contrast, Peeta has no desire to kill, he makes clear that all he wants is for the games not to change him as a person. In District Two, Gale suggests snuffing out the citizens, giving them no chance to surrender because the Capitol wouldn’t afford the rebels the same luxury. Gale gave the idea for a bomb that would lure people in for a second detonation, once again treating people like animals and playing with their lives. Whether or not he was responsible for the bomb that killed Prim is irrelevant. If there hadn’t been someone he cared about in the crowd, he would have been okay with its destruction.

To Katniss, Gale was an escape. She couldn’t lose her one option that didn’t see her as a piece of propaganda. Although she cared for Peeta, she was never given a choice and playing up a romance with him was effectively playing into the Capitol’s storyline, while Gale would allow her to exert some form of agency. The choice between Peeta and Gale was an illusion; it was about a lack of choice. Katniss is stuck as a symbol and she doesn’t want to be, and Gale was her only way out until he wasn’t anymore. Gale isn’t understanding of her situation, he doesn’t care that Katniss has been forced into this romance with Peeta, and instead sees it as a betrayal. He sees her situation as a choice when all she is trying to tell him is that she has none.

She chooses Peeta in the end, not instead of Gale, but instead of being alone. Peeta understood that she saved them, that the romance was necessary and he never forced her to love him as anything more than a friend. She never felt safe or secure enough to think about the future. At no point was she really planning on living to old age exemplified by the risks she takes with her life, even if she isn’t actively trying to kill herself. Her allowing herself to open up to Peeta and accept her feelings shows how safe she feels with him. She can see a future for herself with him and would have kids because she feels secure enough in the fact that they won’t have to go to the games. The end is her version of choosing peace. She has lost so many that being able to exert agency and willingly choose to be with Peeta represents her feeling safe in the idea that she isn’t going to lose him like she lost everyone else. She is safe.