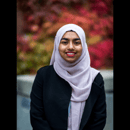

Sometimes, I think about where I come from. I try not to, but memories bubble up, and I’m forced to confront them. I grew up in Mississauga, a few streets away from Square One. The one place I’m bound to run into someone from kindergarten as I’m buying underwear because I guess whoever’s up there has a cosmic sense of humour. I think about everything my parents went through once they moved here from India: Cold winters, a significant language barrier (they moved to Montreal first), racism, an apartment with cockroaches running out of every corner, a baby when they were both in their early 20’s, no car, and no family to support them. I think about how much they hustled to get to where they are today, and how I’m the product of pure grit. After toughing it out in Montreal for a few years, we moved to Mississauga and lived the life of suburbia until I was 13. It was an interesting life now that I look back on it. As a Muslim woman with Indian heritage, I guess, in a way, there was no better place to grow up. I was connected to my culture, and religion, unlike many of my friends who didn’t have a community as I did. I definitely encountered racism as a child, but I thought it was normal. No one could pronounce my name, my hijab always got looks by students and teachers alike, kids made fun of my lunch, so I started throwing it out, and the way I looked made me realize that being Indian was something that was supposed to be ridiculed. But I didn’t know any different, so I internalized it and moved on, as most children do with their problems.

Throughout my childhood, I was constantly surrounded by my culture. We had potlucks every week. Families came to my house with delicious trays of food. There was gossip, the crash, and the bang of some kid breaking a vase, and the sound of loud laughter as the smell of Biryani wafted through all the rooms. Everyone ate to their heart’s content, and by the end of the night, there was always a warm hum. I found myself taking a step back to watch everyone’s happiness. It was beautiful.

But I always watched with a bittersweet feeling. You see, even though I was surrounded by my own people, I was never one of them. The women that came to my house never failed to remind me that I was too dark for a girl and that I was masculine in my behaviour. Even though I grew up with people from my culture, I ended up hating myself. I hated the skin I was born into. I hated that I wasn’t feminine. I hated that my dialect of Urdu wasn’t the same one that everyone else spoke. I hated identifying as an Indian girl because somehow, I couldn’t do it right.

I was outspoken, loud, and didn’t care about the things that other girls did, like makeup and clothes. I didn’t look like the other girls either. I wasn’t fair and dainty; I was hairy. I had a stache going that could probably give men during Movember a run for their money, I had thick eyebrows, and I was short (I still am). But what pained me the most was how restricted I felt. I didn’t feel like I could amount to anything because everyone kept reminding me that I am a girl and girls can’t do the same things that boys can do. I didn’t believe I could be successful, because even at the age of 12, the adults in my life kept reminding me that someday I would have to get married and have a family and that would always come first. I felt suffocated.

I think there was a pivotal moment in my life that marked the end of my self-confidence. When I was 11, one of the aunties (what I call my mom’s friends) had gotten me a dress from India at the request of my mom. I was a small 4’10 girl, but the aunty had brought back a dress the same size as her son, who was much bigger than I was “because she wasn’t sure what would fit me.” It doesn’t seem like a big deal now, but the effect on me was profound. I didn’t even notice it back then, but that’s when I made the shift to wearing baggy clothes, and I started to believe everything people had said about me. I was already insecure about so many things, but then she added my weight to the list. Throughout my childhood, adults that I trusted peppered in stinging comments about my skin, weight, and personality. I can never understand what they gained from picking on a child.

That’s why when my parents decided that we were going to move to Saudi Arabia when I was 12, I was so happy. It meant that I didn’t have to hear anything else that was wrong with me. I could have the fresh start I always wanted.

Moving to Saudi Arabia made me look at life from a whole new perspective. I realized that I was living a very sheltered life in Mississauga. I didn’t know anything about the world. I didn’t know about social or human rights issues or relationships. I didn’t even know what it actually meant to be apart of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community; I just knew it was something that I should never talk about. I didn’t even know that what I was experiencing in school was called racism. It took moving halfway across the world, away from Mississauga, and the people that I grew up with to realize how judgemental and narrow-minded my community was.

When I lived in Mississauga, I thought I would do what all the other teenage girls I knew did; graduate from high school, attend the University of Toronto in Mississauga, and get an arranged marriage in my 3rd or 4th year (if I was lucky, most girls got married right out of high school) because that’s what was expected. Going to Saudi made me independent, and I took the five years that I lived there as an opportunity to unlearn everything that was taught to me. When I left Canada, I left as someone who had very conservative, prejudiced, and uninformed opinions because I knew what the adults in my life knew, and they were stuck in another generation. And by adults, I don’t mean my parents. My parents did their best to ensure that I got to do whatever I was interested in, but then they were subjected to sly, hurtful and poignant remarks from their “friends” about how they weren’t raising me correctly and how I was such an odd child. I was the source of a lot of fighting in my house. My dad wanted to raise me so that I could do everything a male could do, but my mom was always concerned about how our family friends would react.

When I came back to Canada for university, I came back as someone who wasn’t ashamed of being Indian, who tried to believe in herself and her abilities. I came back educated, with informed opinions and someone who wasn’t ashamed of being bold. My boldness was seen as an affliction in my community, but I learned that to make an impact on the world, I couldn’t hold that part of myself back anymore.

The road to recovery hasn’t been easy, and I am far, far away from being okay. It took me a while to realize that the harm that individuals in my community had done to me because there were also a lot of happy memories that I associated with them. There are nights where I can’t sleep because all those comments I’ve been trying to forget flood my mind. On nights like those, I sit on my bed, knees to my chest, and shut my eyes as hard as I can and pray for the morning to come. It’s been seven years, and I’m still trying to convince myself that I’m worth something, that I am valuable, and that I have something to offer. I’m not sure if I believe it yet, but I know that I finally have a community that believes in me, even when I don’t.

I guess that’s a start.