“It is not enough to be ‘not racist.’ You have to be anti-racist.” – The Rev. Thomas Clark, SJ urges his white parishioners to start having difficult conversations in his new speaker event.

St. Francis Xavier College Church kicked off part one of its three-part virtual speaker series, “Ignatian Spirituality and Antiracism: A Call to Conversion” on Feb. 9. The event was headed by the Rev. Thomas Clark, SJ. He is the pastor of Immaculate Conception Church, a historically Black Catholic Church, and the Catholic Chaplain to Southern University in Baton Rouge.

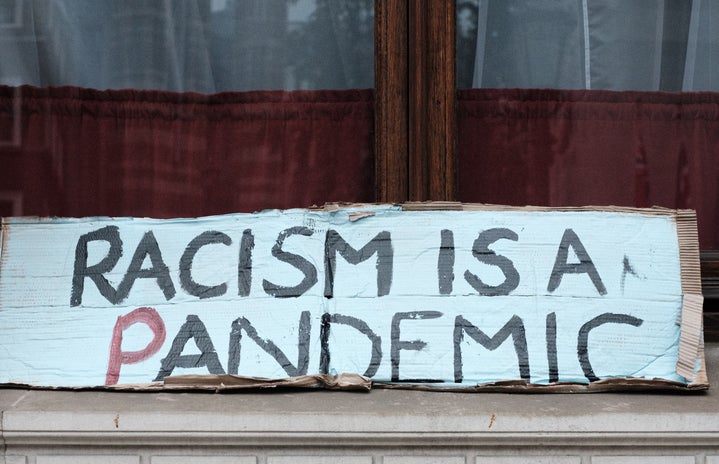

This event was a unique experience and one of its kind. It’s not every day we get to see white parishioners from all over the country come together and discuss racial equity. In celebration of Black History Month, the speaker series calls for conversations, dialogues and reform for racial policies instilled in Catholic institutions. Clark delivers a very personal and informational speech on how Jesuits should challenge the systemic racism around them and why it is important to have these conversations.

Clark starts off his speech by defining some terms related to his presentation. He believes understanding the meaning of terms commonly used in race dialogues is the first step in unlearning one’s racial prejudice. He describes what racism, racial prejudice, white privilege and systemic racism are. He then proceeds to tie all the keywords together to explain to the audience how all of them play a role in hindering Black people’s advancement.

Q (HCSLU): How would you advise learning about critical race theory in institutions?

A (Clark): “It has to start small. We have to plant seeds in people to help them see a different way. It should start with open-minded people. It is a very slow and frustrating process, but it is very necessary and needs to be done.”

“White people are often unaware of their privilege because these privileges are invisible. These are advantages granted to white people due to the color of their skin,” Clark says.

He asserts that when a person with racial prejudice is in power, they have the power to enforce social policies that are dangerous to Black people. Clark gives the example of the Unite the Right rally that took place in 2017. It was a representation of white supremacy and outright racist ideologies. However, he focuses on the fact that the people who participated in that rally—teachers, doctors, police officers, nurses, loan officers, real estate agents, clerks—all returned to their respective workplaces with those racist ideologies and the power to deny access to services and products to Black people.

After highlighting all the issues of systemic racism, Clark delves into the subversive history of the Jesuit establishments in the U.S.

“Slavery is the origin of our country and we never dealt with it,” Clark says.

He informs the audience of Georgetown University’s shameful history of slaveholding. He shares his guilt about always thinking from the perspective of the narrow-minded Jesuits from that era. Now, Clark encourages parishioners and priests to think about the Black people who were sold. He believes having such thought processes will help a person be connected to their Ignatian beliefs and unlearn their own racial prejudice.

Q (HCSLU): How do you empower institutional change in the structure of the institution?

A (Clark): “Institutions change by the member. Especially, it starts from the bottom-up. Lower-level employees need to raise the issue, raising the challenges. Recognize where there is a racist policy or discrimination in their institutions and challenge that.”

Clark shares two techniques with the audience to help them recognize the institutional racism around them. First, he urges people to have heartfelt knowledge. He then shares the anecdote of when he was young and working as a priest in his hometown. He saw a group of Black men on the corner of the street, so he avoided that area and took a long turn to cross the road. Later, when he came across the same Black folks in his church, they jokingly teased him for avoiding them.

“They told me, ‘We did not think you were like that, Thomas,’ and that one line made me realize I am like this and I needed to change that,” Clark said.

He mentions how his viewpoint changed after this incident, when he thought about it from their perspective made the knowledge go from his mind to heart. This is what he calls “heartfelt knowledge”: encouraging people to think about their racial prejudices from their heart instead of their mind.

Secondly, Clark advocates for “courageous conversations.” He says, “The most important thing whites can do is participate in courageous conversations”. This term refers to having those awkward, frustrating conversations about racism with other white people, questioning their racist viewpoints and actions. Those conversations are hard and can be hurtful, but Clark believes they are very important to have. Having such dialogues will further encourage discussion on a broader scale and can boost social reform.