You spot a fancy bookstore while casually strolling in Angel Market and decide to enter it. Once inside, you immediately get an adrenaline rush upon realising there is a Studio Ghibli section right at the centre of the bookstore. As a Ghibli enthusiast, you’re thrilled to discover books with titles claiming to analyse the theme of “sadness and grief” in Studio Ghibli films — you’re sure they’ll include detailed discussions on Grave of the Fireflies (1988) and My Neighbour Totoro (1988). There are multiple other things in that section — eraser sets with the faces of different characters from Spirited Away (2001) and Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), pencils with Studio Ghibli’s name on them in both English and Japanese and fur diaries displaying Kiki and her cat, Jiji, flying on her broomstick. However, your energy levels drop the moment your eyes fall on the cost of each book and diary — none of them are below £20; none of them are worth £20. So, you simply leave the Ghibli section to check out the classics, instead.

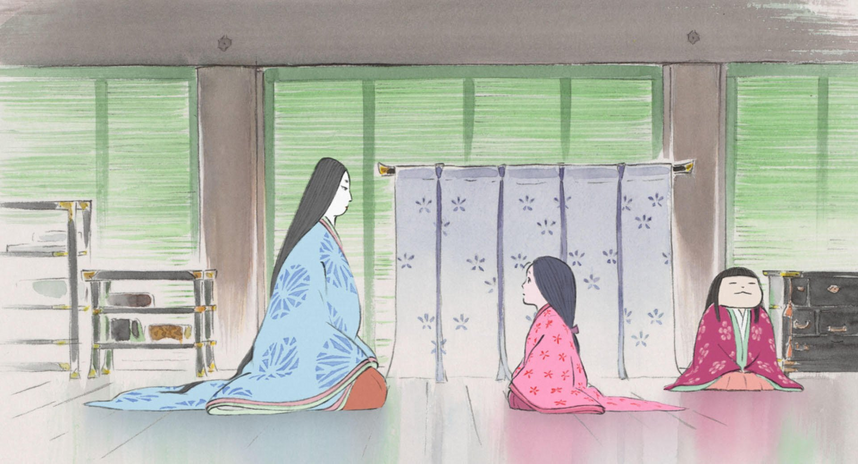

A few months later, your close friends tell you they’re at a quirky store in Brick Lane which is selling tiny lapel pins of Ghibli protagonists which include princess Kaguya, princess Mononoke and Chihiro. “Do you want any of these?” they ask after sending you the images of some of your favourite fictional women with a big, black board that has £8 written on it with white chalk. You immediately refuse stating something as small as the pins doesn’t deserve to be sold for an amount that you could buy your food for over the next three days.

Studio Ghibli, over the past few decades, has given us so many films which either directly or indirectly critique capitalism. Keeping that in mind, Ghibli capitalism somehow goes against those very tenets of Studio Ghibli that have made it so popular among the masses. The animation studio, by creating films like Grave of the Fireflies (1988) and Princess Mononoke (1997) and Spirited Away (2001), has attempted to shed light on themes such as starvation, slavery and the greed of powerful capitalist figures. Thus, it is ironic how Studio Ghibli has, in today’s time, itself fallen prey to capitalism.

When the previously mentioned Ghibli merchandise gets sold for such exorbitant prices, there are many of us who wonder if Studio Ghibli too has become a luxury that only the rich can afford? Perhaps, this is a result of the ultimate Disneyfication of Ghibli — though, Disney merch continues to remain affordable for all. This can, in a broader sense, also be viewed as the west capitalising on Japanese culture which actually is expected out of it, given its inherent nature to exploit.

At the end of the day, those of us who consider ourselves to be Studio Ghibli nerds don’t really need to display expensive lapel pins of Totoro on our bags in order to be viewed as Ghibli lovers. All that is required is for us to recognise Ghibli capitalism whenever we are exposed to it and call it out instead of letting it influence us in any way. We, after all, owe that much to Princess Mononoke and all the tanukis from Pom Poko (1994) who fought against the effects of capitalism.