How he uses radical misogyny to manipulate the masses

In April 2022, misogyny was trending. All thanks to big personalities like Andrew Tate, social media was suffering an epidemic of misinformation. Through too many podcasts, entirely too many men decided their views needed to be spread publicly for the world to see. Under the labels of “kickboxing world champion” and “alpha male”, Tate became the leader of the “manosphere” – an internet ecosystem that mixes self-help advice with threateningly violent misogyny (woman-hating) and misandry (man-hating). However, his celebrity was built on a house of cards; which crumbled at the revelation of his crimes.

When I talk about the trojan horsing of Andrew Tate, I mean metaphorically. He didn’t send a wooden horse into modern day Troy. But what he did was superficially cloak all his crimes in radical misogyny in order to distract the media. Unfortunately, it worked like a charm.

Much like the fabled Trojan Horse of antiquity, Tate’s online persona is a masterclass in subterfuge. What appears to be a gift of wisdom and empowerment is often revealed to be little more than smoke and mirrors. Take, for instance, his infamous tweets espousing the virtues of “alpha male” behaviour, which sparked more debate than a televised presidential debate. Tate’s brand of masculinity is about as subtle as a sledgehammer to the senses. According to him, real men don’t cry, don’t apologise, and certainly don’t engage in any activity that might be construed as “weak.” It’s a philosophy that seems to have been lifted straight from the pages of a caveman’s handbook, complete with grunts and chest-thumping aplenty. He’s not the misandrist society usually likes to rile against, but he is misandric all the same. It’s not all men that he hates, but most of them – anyone who doesn’t conform to the standard of masculinity he loves to deify and ideolise. It’s particularly harmful at a time where men’s mental health struggles are at an all time high, and the narrow view of what a man should be gets smaller by the day. He teaches malleable boys that subservience isn’t just limited to women – that some men are just better than others. He places himself as an omnipotent, omniscient being – as the messiah spreading gospel. He plays God.

By using social media to spread his messages of misinformation, toxic masculinity, misandry and misogyny, Tate is distracting everyone from uncovering the truth. In June 2023, Tate and his brother were indicted in Romania for two counts of rape, human trafficking and forming a criminal gang in order to sexually exploit women. However, these charges are only uncovered if you actively look for them. A quick search of Andrew Tate on TikTok and Facebook shows no evidence of these abhorrent crimes – instead, you see edits of his podcast videos, scrolls and scrolls of misogynistic misinformation, despite being banned on many of these platforms.

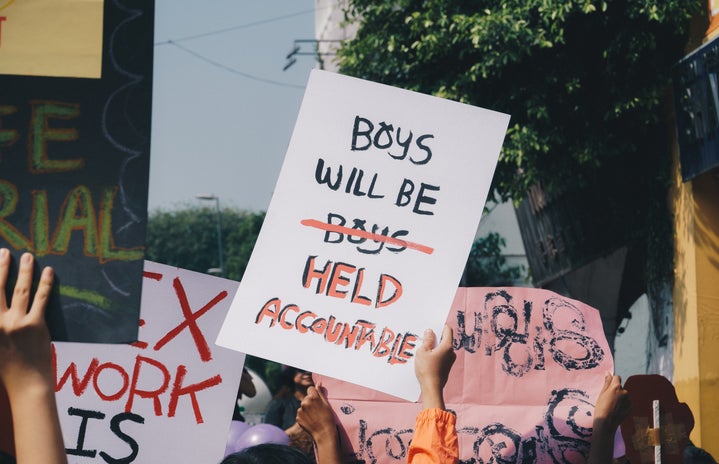

This is not the first time trojan horsing has been used in such a way, and it certainly won’t be the last. Donald Trump famously spewed extremist rhetoric during his rallies in order to push the Overton window (the link is to a fantastic, short video crafted by Vox) in his favour. Named after political analyst Joseph Overton, it describes the ideological phenomenon where politicians use radical and extremist prose to manipulate what is considered politically correct. Anything lying outside the Overton window is considered “outside of the box” and/or radical, and vice versa. Consequently, by repeating far-right, radical discourse, anything slightly right wing seems suddenly normal, and perhaps even politically centre in comparison. Tate takes this technique straight out of Trump’s playbook, because after all, it landed him in the Oval Office. By spouting such rhetoric about women being subservient to men, he allows for the backdoor manipulation of young men who come to think that women are less than their male counterparts. Some men may wholly agree with Tate’s views, but enough believe him to be a facet of truth such that his overall messages of misogyny spread like a virus; this makes him a very rich man. He monopolises this aggrieved entitlement that many white men hold close to their hearts; he teaches men how to step back into patriarchy’s warm embrace from the margins of society of which they have recently come to believe themselves victims.

Andrew Tate’s case of trojan horsing perpetuates one clear message – that a man can only be bad if his actions are bad. No matter what he says, he can usually get away with it, until he puts his money where his mouth is. Society is happy to play along with his misogynistic insanity until a court proves that his messaging can and has been put into practice. Take for example some of the older secret societies/men’s clubs in our little village. These dick-swinging clubs have embodied Andrew Tate’s culture seemingly since time began. They get away with it too – until they act on these subservient spewings. It’s only when these words are manifested into crimes of sexual assault and abuse that societies (that still exist today) are held to account, and given a sharp slap on the wrist. But the public’s consciousness is as shallow as it is scatter-brained, and within a few years, we all seem to forget exactly what goes on behind closed doors. We’re playing right into Tate and Trump’s hands.

So, where does this leave us in the grand tapestry of internet culture? Is Andrew Tate a modern-day hero, bravely leading his followers into the promised land of masculinity? Or is he merely a charlatan in a fancy suit and a fraud? In the end, perhaps the true lesson to be learned from the saga of Andrew Tate is that not everything is as it seems. For every shining beacon of hope, for every messiah of truth, there lurks a shadowy figure waiting to lead us astray.