“When a woman thinks alone, she thinks evil.”

These are words written in The Malleus Maleficarum, also known by its translated title, the Hammer of Witches. Published in 1486 by German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer, the Malleus Maleficarum was the most famous dissertation on witchcraft and punishing witches.

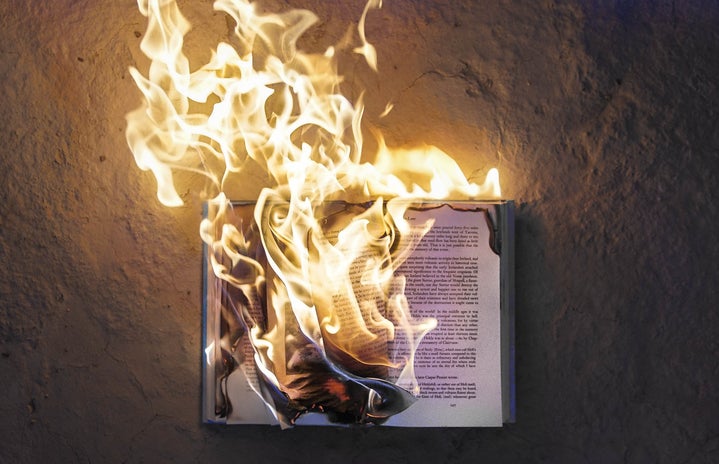

The Malleus claimed that witches worked with the devil and posed a serious threat to society and, thus, should be burned alive at the stake like other heretics. The arguments pushed forward by this book added immense fuel to the already rapidly growing fear of witchcraft.

From the 14th to 18th century, mass hysteria and a witch-hunt craze swept across Europe and North America. You may already be familiar with the infamous Salem witch trials, but the bigger picture is even more unsettling.

Every Halloween, we are constantly surrounded by figures of the witch as prototypically female. But why are they always women?

Around 60,000 to 100,000 people were persecuted on accounts of witchcraft between the 14th and 17th centuries, but only an estimated 10-30% were men.

So, what made women so much more likely to be accused of witchcraft?

In short, women were seen as morally weak, inherently tainted, and evil in nature. It was widely believed that women were more susceptible to influence from the devil and had insatiable carnal lust, so they would have sexual relations with the devil to fulfil their desires.

Female sexuality was thought to be unnatural and rooted in evil, paired with the idea that women should be naturally submissive to men. Quite literally, anyone accused of female sexuality was persecuted.

Women were viewed as inherent enemies of the Church and the State and were considered political, religious, sexual, and societal threats. The Malleus heavily pushes this, as did many other sources, including the Church itself.

The scary thing is that these weren’t underground hunts or a few crazed people with stakes — these were completely legal processes, persecutions, and actual laws that were put in place to deal with witches.

This wasn’t random. It wasn’t isolated. This was systemic. It was fully, 100% legal.

The witch hunts were a systemic and institutional method of silencing women and upholding the patriarchy. Of course, women can’t challenge the status quo when you cage them and kill them.

Any woman who didn’t fit the mould created for her by the patriarchy was seen as evil. This included unmarried and widowed women, older women, peasant women, healers, and midwives.

While the male upper middle class was freely allowed to practice and receive healing and healthcare, women who practiced healing were deemed witches. The Church feared the implications of people, specifically peasants and women, discovering how to rely on their senses and logic rather than faith and religious doctrine.

While you may picture witches as malicious, dangerous, and scary, the historical truth of it all isn’t quite as nightmare-inducing. Most “witches” weren’t harming people — in fact, the exact opposite.

The vast majority of women accused of witchcraft were healers or simply unconventional in society. However, women couldn’t even help people without being deemed Satanic.

Not only were women not allowed to heal people, but they also couldn’t be around someone or something that died. Simply having a child or animal die under your care could have sparked accusations of witchcraft.

Women were expected to do all the labour associated with domesticity, including raising children, tending to crops and animals and handling food products. This made women the frontline of preventing decay and the first people to receive blame when rot or death occurred.

Infant mortality during this time was high, and losing a child could have led to accusations of malicious witchcraft and foul play.

Livestock death could also spark witchcraft accusations, and so would food rot. Any sort of natural decay was seen as corruption and thought to be magical sabotage.

“Gendered divisions of labour contributed to the predominance of female witchcraft suspects,” said University of Cambridge professor Dr. Phillipa Carter in an article on witchcraft accusations against female workers.

The role women were forced into and expected to fulfill inherently put them at extreme risk of being labelled as corrupt in a society that already believed they were morally corrupt.

It was seen as unnatural for a woman to have a profession outside of domestic labour. Like it or not, if you were a woman, you bore all domestic responsibility and all the blame for natural death and decay.

There was no way to escape the threat of witchcraft accusations. Whether you adhere to the expectations or not, you will be branded a witch either way.

It’s quite frightening to think about how the witch-hunt craze suffocated female individuality and the raw power of women — no magic involved, just strength, intelligence, and potential.

Reading about this reminded me of a YouTube video by creator FunkyFrogBait, where they dissected the rise of TikTok “trad wives” and the current impacts of patriarchy on women.

“How many Einsteins have spent their lives washing dishes?” they ask in their video. “How many Mozarts bent over stoves instead of pianos because they had the misfortune of being born a woman?”

And it’s a startling realization: how many great minds have been lost to oblivion because it was a woman’s mind? How many female geniuses have the patriarchy muzzled and killed?

In this context, it’s no surprise that it was a man who invented the lightbulb, discovered gravity, invented the printing press, and many other inventions of that time — only men were granted the privilege of innovation.

Behind every woman who dared to dream of a better world, there was an angry mob of pitchforks and torches screaming, “Burn the witch!”