When I told a copy editor that I wanted to be a journalist, the first word out of their mouth was “don’t.”

“It’s a tough world out there, especially for someone who wants to be taken seriously,” they said, not realizing 13-year-old me had stopped listening altogether, and started to have a minor-level panic attack as my finally concrete career plan had come crashing down around me. We rambled on for a while: them complaining about the reality of being a woman in journalism and me trying to keep up. But one thing they said stayed in my mind: “You get one exclamation mark in your career. Use it wisely.”

But later studies have gone on to show that using an exclamation point in a professional setting is an excusable act if you’re a woman, yet a big faux pas if you’re a man. So, why is it journalism’s problem?

Let’s go back and unpack this phenomenon. When the exclamation point was just a young puntcus exclamativus, the Italian poet Lacopo Alpoleio da Urbisaglia decided his brand new linguistic invention was labeled a phrase that should be read aloud in a livelier fashion. It was quickly used to adorn phrases of exclamation or admiration (or horniness) — something I find rather romantic.

It’s a kind of infatuation, both with the addressee and with the words weaponized. In Shakespearean times, exclamation points were used to follow exclamations. It’s estimated William used over 6,000 exclamation points (although it’s contested that it was the printer who soiled his work). His plays utilized the exclamation mark for quotes such as, “Alack the day, she’s dead, she’s dead, she’s dead!” in Lady Macbeth and, “Lo, how he mocks me!” in The Tempest. The mark noted a point at which the reader’s attention was needed. In short, it signals a feeling.

Moving forward in time, the mark became a notifier of passion. Herman Melville’s, Moby Dick had 1,683 exclamation points, and James Joyce used over 1,000 in Ulysses. But soon enough, the mark went out of fashion. During the boom of the printing press, the exclamative was heavily associated with ostentatiousness and sensationalism, often found in newspaper headlines. At the same time, the mark began to receive criticism due to its “overuse” by female authors, which were referred to as “sentimental novels” at the time.

Mrs. Southworth’s, Hidden Hand and Her Mother’s Secret used 1,580 and 1,834 exclamatives respectively, which mirrors Melville’s rate of usage. Using the mark thus quickly became over-dramatic, fanciful, unmanly, and disdained. To avoid the exclamation mark was to be taken seriously.

F. Scott Fitzgerald was among the critics. Initially a fan of the mark, the 1930s brought with him a disdain for exclamations. Sheila Graham, in a memoir of their affair, wrote that Fitzgerald once told her that using “an exclamation point is like laughing at your own joke.” Such a view has gripped authorship since.

However, the story of the exclamation mark rests in the acceptance that prose used to be read aloud and not something accessible to a much larger scope of the population. This is why advertisement continues to abuse the exclamative, while journalism and literature have steered clear. The advertisement industry misinterpreted the meaning of da Urbisaglia’s punctus admirativus, thinking it meant you fell in love with the mark itself. On the other hand, the mark was adopted by the comic book industry on the basis that you simply don’t take it too seriously. Both industries rely on grabbing the reader’s attention, but not retaining it for passages of prose.

At the same time, women were starting to find their positions in the workplace. In a position of authority, especially one regarding literature or oration, a woman has two requirements to fulfill. Should she choose to play the good woman, she’ll be well-liked but wrongly underestimated. However, if she fulfills the requirements of an authority figure, she’ll be respected but simultaneously referred to by a word that begins with the letter “b” — bossy, of course. Full stops became too stern, so exclamation marks became code for nice.

Naturally, the journalist was right. Exclamation marks had become a gender issue. 73% of exclamations were made by females and only 27% by men in online correspondence.

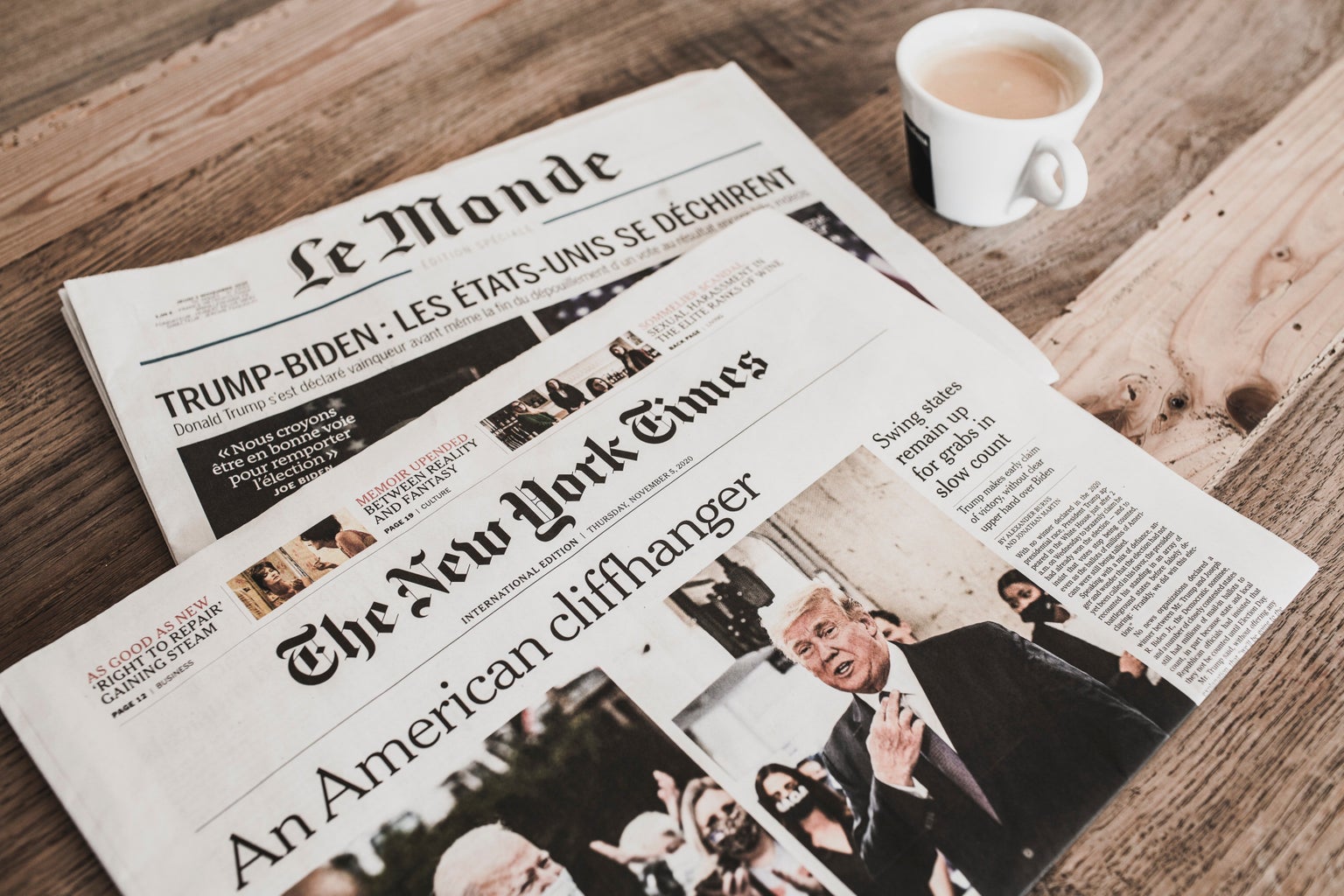

But one particular man used and abused the mark more than Herman Melville, and more than your average Snapchat group planning brunch: Donald Trump. Linguists have been quick to accuse him of “upscale graduation” with over one-third of all his tweets including an exclamation. As much as I love to criticize Trump, what he’s doing here is a clever tactic. Studies continue to show that an audience feels “closer” to a speaker who uses an exclamative as it signifies someone being more passionate and open. Thus, it’s a useful tactic for swaying the masses towards your side.

This leads me to mainstream journalism. Now that the exclamation mark is unpopular, news organizations that like to take themselves seriously (eg: the BBC, CNN, MSN, ITV, etc.) shy away from using exclamations. Their role is to inform, not to convince, sway, or adore. They must grab your attention and keep it.

They do this by using figurative exclamatives. When reading off a teleprompter during a news broadcast, the scriptwriter will punctuate the story with exclamation marks to indicate tone. It’s to inject sincerity, and just like Trump, a linguistic technique that forces the listener to like, and thus, trust the stranger on the television.

The reason why that journalist told 13-year-old me to stray away from exclamations is because broadcast and print journalism is a serious business. Throw one exclamation mark into the mix and suddenly you’re a wannabe Mrs. Southworth, and you’ll never be taken seriously again. Such logic suggests that the exclamation mark should be left to crackpot old fools, overexcited teenage girls, insincere apologies, and the occasional Florida man headline.

Alas, I choose to believe the lexicographer Fowler brothers when they said, “How you punctuate your sentences might have something to do with how you punctuate your life.” I may be a British cynic and consequently shy away from exclamations of any kind, but that’s not to say you should. There’s a place for sincerity and stoicism, but there’s also a place on the internet for a little bit of fun. Whether you prefer the literal “!” or more figurative exclamations like emoticons, emojis, memes, or gifs, the internet is and always will be a silly place for silly things.

P.S. If you’re interested in exploring the future of the exclamative, Netflix’s Explained goes into depth on the “interrobang” (a personal favorite punctuation of mine). It’s accessible for free on YouTube and has been my supplier for many of the statistics used in this article.