This article will contain spoilers, but the play is some 400 years old so I will assume it will be okay.

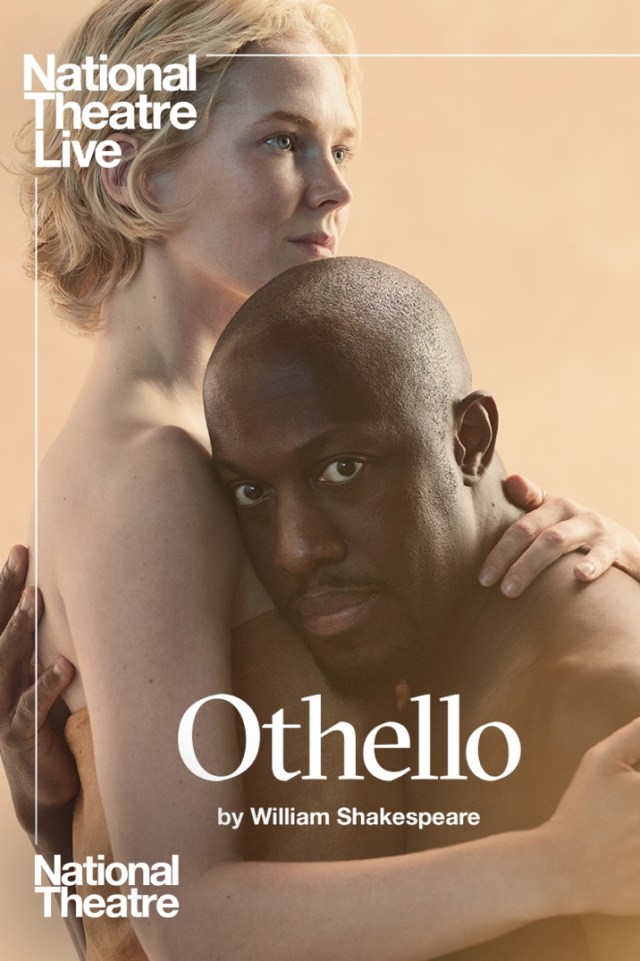

If you’re like myself and love free theatre, then you are probably missing the wealth of accessible theatre that was being streamed during lockdown. Well, the National Theatre (NT) heard those calls and streamed its 2022 production of Othello on October 18th on Youtube. I had seen this production in its run in December 2022 and on the second watch, it was just as topical and thought-provoking as the first time.

Shakespeare’s Othello follows the story of a Moor general in the Venetian army and his relationship with a white gentlewoman named Desdemona. It opens with the news that Othello and Desdemona had married in secret, against her father’s and much of the society around them’s wishes. However, Othello and Desdemona’s relationship is allowed to remain due to Othello’s status as a powerful and skilled general, as he states upon being accused of wrongfully coupling with Desdemona; “My parts, my title and my perfect soul/ Shall manifest me rightly” (I.2.31–2). It becomes very clear that Othello fails to consider the way racism viciously infects the society around him, especially through the character Iago.

Iago, the antagonist of the story, has been overlooked for the position of Othello’s lieutenant for Micheal Cassio and thus holds a strong grudge against both Othello and Cassio. He vows to set forth a plot that will have Othello convinced Desdemona is unfaithful and will kill her.

While this is a simple summary, the play contains much more including discussions on class, gender, domestic abuse, and the cost of success for minorities. However, probably the most formative and terrifying topic that appears in the play is the power of language and its weaponisation through racism. However, this topic, some may argue, is too modern of a lens to be placed onto the play, and whether Shakespeare intended to write a racist play or a play about race is a question of fierce debate. But the NT production does not seem to shy away from this subject nor its debates.

The NT’s production creates an expansive world in which the play itself becomes a warped version of a courtroom, where the audience and the ensemble is the jury and the characters of Iago, Othello, Desdemona and Emilia all must fight their cases. But this would never be an equal courtroom and Shakespeare’s original text and much of its performance history of blackface and racism does not allow this. This is especially re-affirmed by the very beginning: when the play opens, the stage is covered in projections of various productions and playbills throughout history, along with changing dates from the very beginning of the history of the play in the early 1600s to the present-day. This is a production that sets out to be aware of its own history before the characters even step on stage.

Interestingly enough, the first character we see is an unnamed man, who is mopping up what appears to be a puddle of blood, very much indicating the bloody affairs to come. It is profoundly reminiscent of the epic tradition of knowing the end before the story has begun. The original text has no chorus and no descriptor besides the title, and yet the NT production chooses to give it a silent one: this is a story that has already happened and this is a story that will happen again.

The play’s set is bare and cold, it’s all grey concrete and creates a militaristic atmosphere, which is only furthered by the black and grey military garments everyone wears. With the expectation for the ladies of the play, (Emilia, Bianca, and Desdemona) the men all wear suits and military gear, however, Othello notably wears clothes that are inspired and reflective of his African roots, which remains an odd contrast to his speeches which seemed to reject this connection. His clothes from the beginning set him out as an ‘other’ in a society filled by white men and women.

Notably, the play does not begin like the original script does, and this, I believe, was one of the unfortunate faults of this production. The original script opens up with Roderigo and Iago, both white men and both soon to take part in the business of breaking up Othello and Desdemona, the first line usually spoken on stage is; “Tush, never tell me.” The removal of this line is in conflict with the way the rest of this production focused so heavily on putting a spotlight on the audience and the way language can become weaponisation for racism in society. The original play begins with the idea of not wanting to know something, which would have well served the image of cleaning up the blood before the beginning of the show. We don’t want to know what is about to occur but it is already set in motion and we are already familiar with what is about to happen. Moreover, the line is spoken by a white man, which can further emphasise that white people are too uncomfortable to want to know the systematic racism of the society they live in and the privileges they benefit from.

Instead, this production has brought Othello to the forefront and allowed him the chance to be seen in the first scene of a play that is named after him, where the original text and other productions do not. In the original text, Othello is neither named nor appears until scene 3.

The rest of the play is then a verbal battle between Othello and Iago, as well as a battle of gender roles and expectations with Desdemona and Othello as well as Iago and his wife, Emilia. Emilia, played by Tanya Franks, gives a gut wrenching speech about the abuse of husbands towards their wives. Franks plays a broken-hearted woman torn between her abusive husband and the love she shares for Desdemona, which, although it has caused debates about being romantic or platonic, remains a powerful testimony to the love between women all the same.

Across from her Rosy McEwen plays a poised Desdemona – A woman who knows her position in society as a gentlewoman and the wife of a general. However, she fails to understand her fall in social standing due to her marriage to Othello and the way that racism has begun to infect her husband’s disposition. Her song of Willow came to be especially heartbreaking as she folded her clothes and prepared her marriage bed one last time.

While I could go on and on about each careful detail, I will, for time’s sake, focus on the final scenes of the play and where I believe this production has earned its dues as a fantastic adaptation.

The final scenes of the production affirmed the exact vision and its successes. After killing Desdemona and learning the truth of her loyalty, Othello, played by Giles Terera, stands cornered with guards ready to take him away. He then gives a heartbreaking speech that asks the characters and the audience to speak of him kindly after the events of the play; “Then must you speak/ Of one that loved not wisely but too well;/ Of one not easily jealous, but being wrought/ Plex’d in the extreme”. Terera plays this speech as much to the characters as the audience itself, he pleads with us, even as he remains composed, to view Othello’s behaviour as a response to the racism around him. While this works for a pre-recorded production to watch at home, I believe it was particularly effective in live performance. When the play closes, the hundreds of people shuffling out of the theatre will begin to pass their judgment on the performance, on the actors, and mostly on the characters actions themselves. The NT production was thus not just aware of its history of performance, but of the very action of performance and nature of theatre happening in that very moment.

The final lines of the play are notably given to Iago, when asked why he would do such a thing, as all the characters stand over the bodies of Othello, Desdemona, and Emilia he finally states: “What you know, you know.” This is a single line in the original text, but the NT production expands this entirely, having Iago repeat it and repeat it and repeat it until he is yelling at the audience until it becomes not what the characters know but what we the audience know. We were complicit in every action of the play, we watched and listened to Iago’s soliloquies and then watched as he enacted his revenge on Othello and the other characters. But moreso, we know this racism, this is the racism of our society, not some distant past one. We see this viciousness every time Black bodies are dehumanized whether it be white woman calling the police that a black man, who is standing several feet away, is attacking her or a 17-year-old black boy being forcibly held down on the ground and arrested by British Transport Police in a case of mistaken identity.

This production wanted to place a mirror on ourselves and our society, that Othello is neither a dated play, nor simply a play that lacks value because it’s racist. Instead, it is a play that can be constructed and produced to display the way that its events are not far off from what we see on our news every day. That nothing more has to be said at the end of this production, because we “know” exactly what it is Iago is referring to, and that we know that, like the very beginning of the play, this will continue, because someone will mop up the blood of the past story in order to make room for the next.

The NT’s production of Othello is available on NT at Home now.