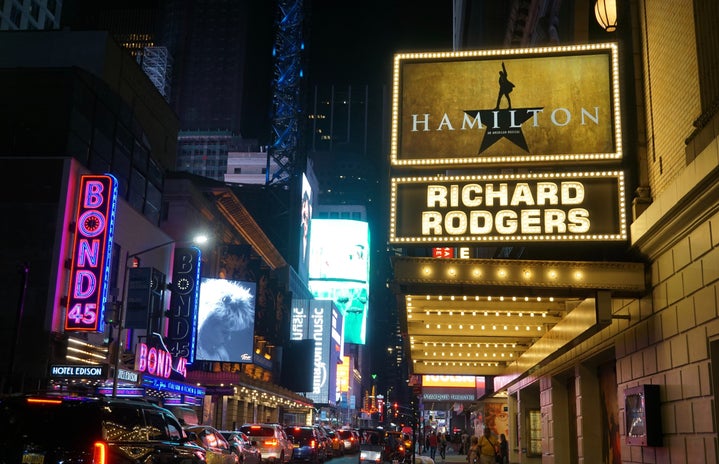

On August 6, 2015, the world turned upside down when Hamilton premiered at the Richard Rodgers Theatre on Broadway to near-universal acclaim, rocketing into mainstream media like few other musicals have before it. It details the life and legacy of Alexander Hamilton, following him throughout his life, from his time as George Washington’s aide-de-camp to his life being cut short by a final shot from Aaron Burr.

Originally, this was going to be a retrospective of how well the musical holds up almost a decade after its initial premiere. But, as I listened to the soundtrack and watched the filmed version released on Disney+, what ended up captivating me the most wasn’t just the music or the choreography, but the relationship between Hamilton and Burr. The musical delves into their respective psyches, exploring how their dynamic flourishes and withers over the course of the Revolutionary War, and the years after that spent building a new nation together.

“Aaron Burr, Sir” immediately establishes Hamilton and Burr as foils for each other, with Hamilton desperate to make a name for himself by any means necessary — in this case, using the war as a catalyst to ensure his legacy in the history of a new nation. In act one alone, Hamilton makes himself indispensable as Washington’s right-hand man in the eponymous song, delivering rapid-fire strategies to deal with their lack of men, information, and supplies that secure him the position Burr had been vying for just moments ago. Shortly after, Hamilton is quick to seduce and wed Eliza Schuyler during a winter’s ball — both the historical event and the song of the same name — subsequently elevating his status and jettisoning him out of the life of poverty and self-sufficiency he’d been forced to endure.

Meanwhile, Burr, who is already saddled with the responsibility of protecting the legacy of his deceased parents, is “chronically cautious” in everything he does. His signature motto of “talk less, smile more” informs his constant refusal to be upfront about his ideals and political beliefs throughout the entire musical, from simultaneously refusing to publicly show his support for the Revolutionary War to never offering his political beliefs during the presidential election of 1800.

Burr’s willingness to adjust his beliefs depending on his current situation is shown more subtly during the song “Right Hand Man”, where Washington makes his debut and eventually recruits Hamilton as his aide-de-camp. When Washington loses his composure and sings the lyrics, “Are these the men with which I am to defend America?/We ride at midnight, Manhattan in the distance/I cannot be everywhere at once, people/I’m in dire need of assistance”. Not even moments later, Burr is quick to repeat Washington’s own lyrics, shaping his beliefs to mimic the general’s instead of standing by his own: “I think that I could be of some assistance/I admire how you keep firing on the British/From a distance”.

It’s at the climax of act one that the rivalry between Hamilton and Burr begins to face mounting tension. “Non-Stop” serves as a montage for the lives of Hamilton and Burr after the war, where the former’s work in law has propelled him into a position of heightened renown as a lead counsel, a delegate for the Constitutional Convention, the main author of The Federalist Papers, and a cushy new job as the first-ever Secretary of the Treasury. Meanwhile, Burr merely stands by and watches Hamilton rush forward for the entirety of the song, refusing to help him defend the Constitution and repeatedly condemning him for stating his beliefs so openly.

During act two, however, Hamilton and Burr essentially swap their modus operandi, with Hamilton utilizing Burr’s strategy of “talk less, smile more” to surprisingly great effect. This is most prevalent in my favorite song, “The Room Where It Happens”. It is sung almost entirely from Burr’s point of view, and he details how Hamilton successfully strikes a deal with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison — Hamilton’s two greatest enemies — to secure his desired financial system in exchange for moving the capital closer to the slave-owning South. All the while, Burr remains envious of Hamilton’s ambition and success, before finally admitting at the climax of the song his desire for political power and to leave his mark on history.

This is when Burr attempts to do what Hamilton did in act one and take his shot, changing his political party to Democratic-Republican and beating out Philip Schuyler — Hamilton’s father-in-law — for his Senate seat in “Schuyler Defeated”, and later openly campaigning against Thomas Jefferson during “The Election of 1800”. However, while it may seem effective on the surface, he’s only doing so for personal gain, rather than for his own beliefs. This is what causes Hamilton to endorse Jefferson despite their long-standing enmity, as Hamilton so aptly explains to the audience: “But when all is said and all is done/Jefferson has beliefs. Burr has none.”

“The World Was Wide Enough” serves as the culmination of years of animosity between the former friends, wherein Burr has challenged Hamilton to a duel in Weehawken, New Jersey after Hamilton’s decision to endorse Jefferson in the presidential election was a slight too great. Interestingly, Burr’s lyrics throughout the song are permeated with his rage at Hamilton’s betrayal of their friendship and his paranoia that Hamilton, “a soldier with a marksman’s ability”, will manage to shoot him first and end his life.

By contrast, Hamilton, who doesn’t sing at all until he aims his pistol at the sky and sings a line from “The Story of Tonight”, is much calmer during his internal monologue about the legacy he’s going to leave behind, about what will happen if — when — he finally decides to throw away his shot. And by the end of his monologue, he’s accepted that he’s going to die, having seen glimpses of his dead friends and family on the other side. And after he tells Eliza to take her time, that he’ll see her on the other side, he slowly raises his pistol to the sky, letting Burr, “my first friend, my enemy”, take the shot that ends Hamilton’s life.

Not only is Hamilton a story about the founding father lost to time, but it is also about the decades-spanning relationship between two people who will meet again and again throughout their entire lives. It is deeply compelling to see Hamilton go from idolizing Burr at the start of the story to refusing to endorse him during the presidential election, and likewise, to see Burr go from offering Hamilton well-intentioned advice to ending his life. Their relationship is highly complex and tragic in equal measure, and it isn’t difficult to see why hundreds of thousands of people returned to see them cross paths on stage again and again.