*Spoiler alert for Troilus and Criseyde by Geoffrey Chaucer

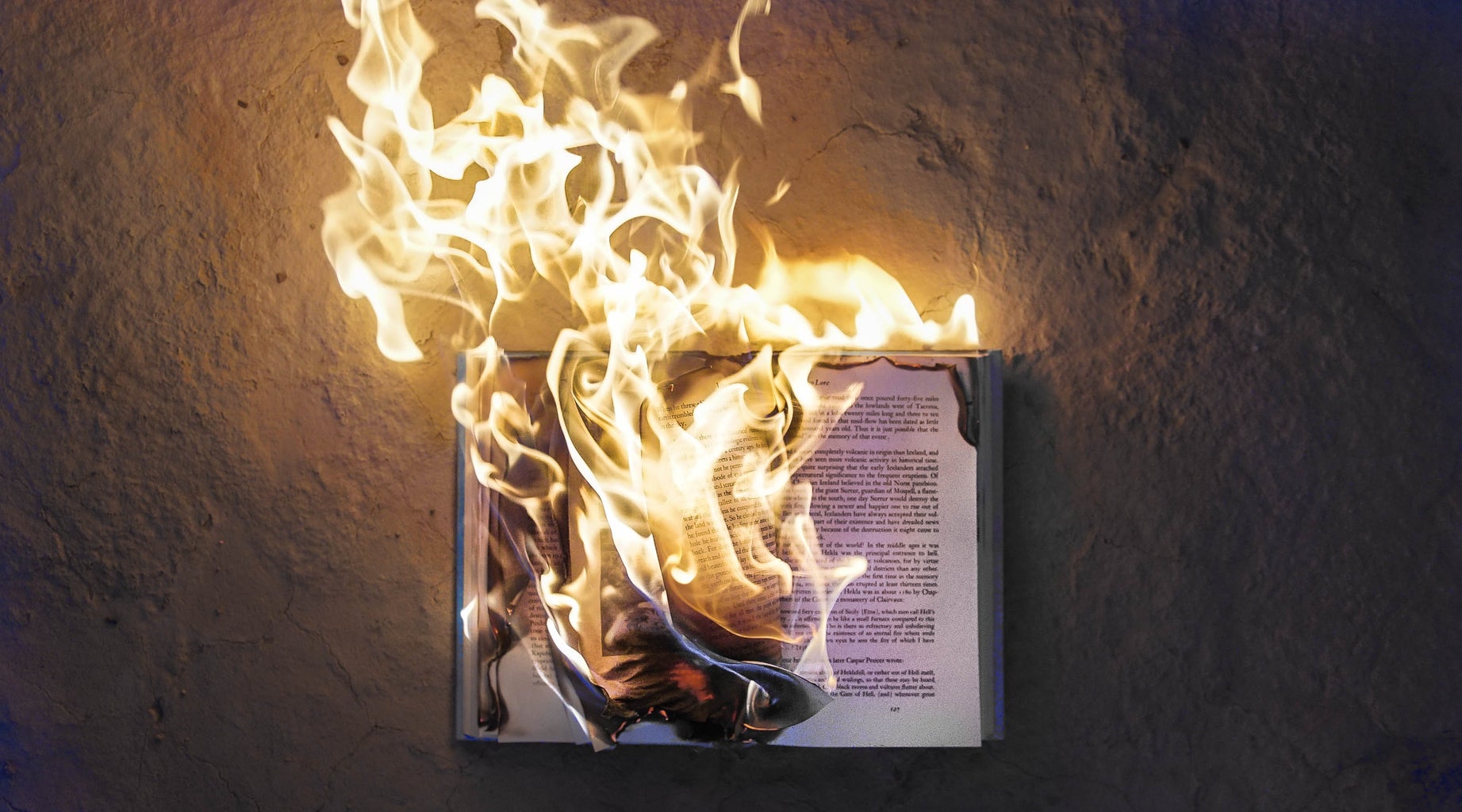

Ever since learning about the English poet, Geoffrey Chaucer, there were very vague impressions I associated with this man. All I knew was that he wrote the Canterbury Tales and that it was written in Middle English. However, upon taking a course called “Chaucer: Troilus & the “Minor” Poems,” I was able to be more appreciative of his writing and long-lasting legacy, especially pertaining to his imagery and depiction of human relationships in his work called Troilus and Criseyde. It is a complex narrative about two star-crossed lovers navigating their doomed love at first sight (literally, because the god of love forced Troilus to fall in love with Criseyde after he scoffed at couples and diminished love to be an emotion for fools).

The reason why this was a punishment was due to the fact that they were an ill-fated pairing. This alludes to their social backgrounds and difference in social isolations — Troilus and Criseyde could not be freely together in public (or private) as Troilus was the prince of Troy while Criseyde was the daughter of the traitor (as her father betrayed the nation since he deflected to the enemy nation during wartime). As such, their relationship appeared passionate and desperate on the surface as their brief meetings always had an underlying current of unease and anxiety of getting caught at any moment, but their lack of physical interactions and possessions of each other (outside of their inconsistent, fleeting, and nightly coupling) served to accentuate and suggest that their lack of a physical foundation in their first meeting also translated over to a lack of strength in their overall relationship.

Their lack of physical interactions and connection was continually reinforced throughout the narrative, with their inability to be physically close to one another gradually revealing their inability to perceive each other as tangible and empathetic thoughts. One of the biggest examples of this was when Criseyde had to leave Troy for Greece as the nations had agreed upon a “prisoner” exchange (where Criseyde, a civilian, was exchanged for an imprisoned warrior), which the couple could not prevent without exposing their secret relationship — and as such, they were unable to protest against Criseyde being taken away. This meant that their only mode of contact was severed, and their relationship rapidly deteriorated after this physical separation.

After Criseyde unwillingly left, Troilus went to her empty house and bemoaned her absence. In the middle of his lamentation, however, he compared it to an empty saint’s house in which this metaphor of seeing her house as something sacred and untouchable (therefore distant) once again emphasized their difficulty in being able to internalize each other, making the other inaccessible even in their minds. The lack of physical, tangible trinkets or reminders of each other not only limited their emotional processing but also negated any attempt of verifying their relationship and possessing each other (internally and externally).

As Troilus could only rely on his internal image of Criseyde as the object of his sorrow and love, his attempts to come to terms with his loss are made unconsolable as those sentiments were directed at someone who he could never truly own or prove was his.

For me, the part that tied together this dilemma altogether was with this imagery at the end of the narrative where Criseyde falls out of love with Troilus: “For bothe Troilus and Troye toun / Shal knotteles thurghout hir herte slide”– which roughly translates to “for both Troilus and Troy slide through her heart without a knot.” The idea of Troilus being represented as a knotless string that passes seamlessly through Criseyde’s heart goes to accentuate their inability to provide a sense of security for each other through neither physical, and therefore, abstract means. I interpreted this scene to be suggesting that the role of physicality in relationships is related to attempts to validate, physicalize, justify, possess, or even gain ownership of concepts or people, in this case, that is otherwise intangible and unverifiable.