Rising tides, melting glaciers and devasting wildfires have pushed the topic of climate change to the forefront of consumers’ minds. With corporations such as The Coca-Cola Company, PepsiCo and Nestlé being the worst climate polluters in the world, there is a push toward conscious consumerism (also known as ethical or responsible consumerism).

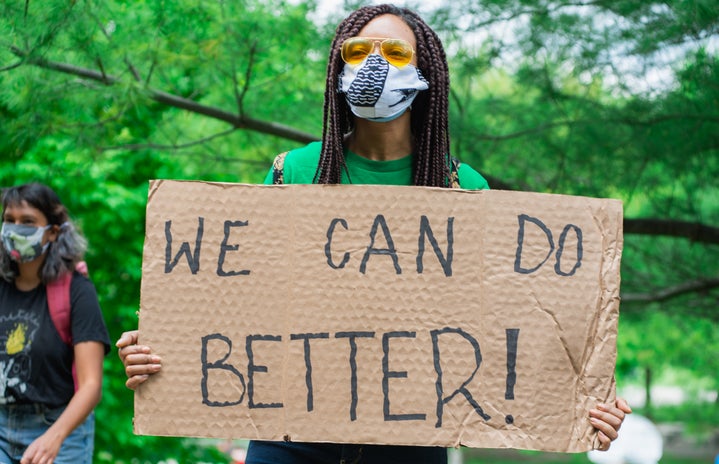

Conscious consumerism is a buying practice that is driven by a commitment to making purchasing decisions that have a positive social, economic and environmental impact. As consumers in a capitalist society, we are encouraged to believe that our greatest weapon is our purchasing power. The logic is as follows: we can bring about change through boycotting companies; to protect their business, companies are forced to conform to consumer demands and switch to sustainable practices. What we fail to take into account is the incompatibility between capitalism and sustainability.

Capitalism is a socio-political and economic system of trade characterized by private ownership of capital goods in which prices are determined by free-market competition. Social media debates on the topic of capitalism tend to mention the concept of ‘infinite growth’ and how ‘infinite growth’ is an impossibility in a world with limited resources.

The academic origin of this argument is found in “Capitalism’s Growth Imperative,” a 2003 journal article by economist Myron J. Gordon and statistician Jeffrey S. Rosenthal. They argued that capitalist firms are subject to a growth imperative because the risk of bankruptcy is too high when there is a zero or negative growth rate. Therefore, to survive, firms require a positive growth rate.

The question emerges: can capitalism ever be sustainable? In theory, maybe. In current practice, no. The most cited definition of sustainability comes from the “Brundtland Report,” published by the World Commission on the Environment and Development in 1987. The report defined sustainability as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. In addition, the report developed guiding principles for sustainable development and formulates strategies for environmental conservation.

Since its publication, the report has been used to inform legal regulations on greenhouse gas emissions all over the world. However, the drawback lies in the very nature of the document. It is a report and therefore carries no legal weight. The implementation of the principles and strategies outlined in the report is sporadic and varies from country to country.

Consumers calling for corporate environmental responsibility is not met with actual changes toward sustainability because capitalist firms can’t risk lowering their growth rate, aka profits. Instead, what we see is the corporate distortion of the concept of sustainability. Through strategic marketing, we are told that we should purchase certain products if we care about the environment.

The first example that comes to mind is the recent rise in popularity of Hydro Flask reusable water bottles. Hydro Flask is a brand that has an association with being environmentally friendly. As an owner of a Hydro Flask water bottle, I can attest to the high quality of the product—with high quality comes high costs.

However, the problem lies not in the price itself but the social pressure to own one. Somehow, owning certain products such as a Hydro Flask or reusable straws have become synonymous with caring about the environment. This dilemma applies to more than just this brand and their water bottles. I have seen just about every product rebranded as ‘eco-friendly’ with a simple change in green packaging and materials that are supposedly ‘sustainably sourced.’

This is not to say that as consumers, we shouldn’t be conscious about which companies we are buying from. The fact of the matter is that many companies are using social media and marketing to distort our understanding of sustainability and misleading us as to the environmental impact of their business practices. There is no nicely wrapped conclusion I can end on, only a reminder that we cannot take corporate marketing at face value.