For years, my feminism was embarrassingly naive. It was a product of the inoffensive corporate slogans that are performative by design and their palatable, apolitical “girl power” media campaigns that ran rampant during my formative years and continue to do so today. Regarding all women as my allies was an enchanting mindset to the teenager I was, who often felt so alienated from other women as a result of her queerness and neurodivergency.

But just because an idea might appeal to the optimist in you doesn’t mean it’s not disastrously untrue. Experiencing xenophobia from women who called themselves progressive, I learned the hard way that turning off your critical analysis of a situation just because the person speaking identifies as a woman is the quickest way to sabotage feminism.

Hooks speaks on how we need to distance ourselves from this oversimplified mentality perfectly in her chapter “Consciousness-Raising: A Constant Change of Heart” in “Feminism is For Everybody” when she clarifies “one does not become an advocate of feminist politics simply by having the privilege of having been born female.” Now more than ever, we need to make sure we’re not falling into the trap of believing a woman is inherently our political ally because of her gender—just consider supreme court justice Amy Coney Barrett or the rise of trans-exclusionary “feminists.”

How hooks emphasizes feminism as a political agenda and stresses that we work to distinguish who our political enemies are from who might be a potential ally in need of guidance is exactly what I found so incredibly valuable about reading “Feminism Is For Everybody.” Gauging political allyship based on the work someone has put into helping the movement is something we should all get accustomed to doing.

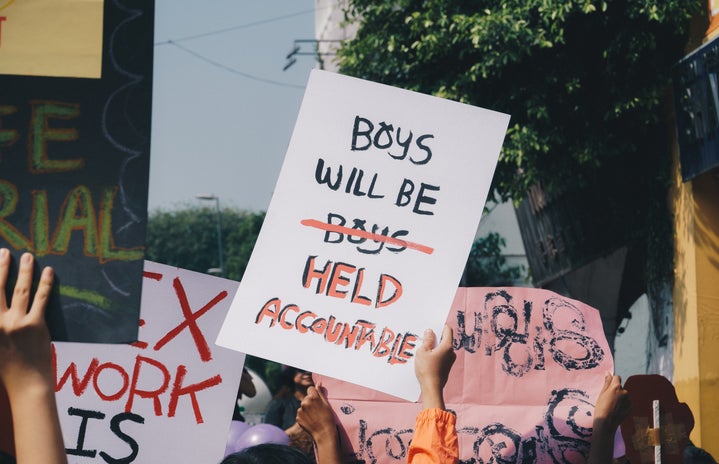

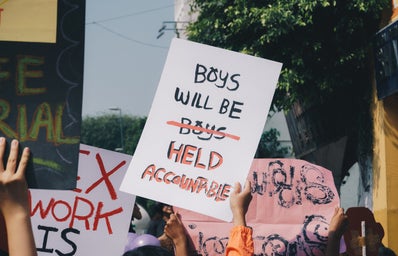

As Hooks puts it in the same chapter on consciousness-raising, “A male who has divested of male privilege, who has embraced feminist politics, is a worthy comrade in struggle, in no way a threat to feminism, whereas a female who remains wedded to sexist thinking and behavior infiltrating feminist movement is a dangerous threat.” This insight alone informs so many of my current-day analyses when it comes to topical issues like faux representation; I would recommend this particular chapter to everyone who believes in anti-sexism.

Similarly, hooks’ chapter “Feminist Education for Critical Consciousness” really resonated with me in how it calls for increased accessibility in the feminist political movement. Having navigated through academia for the last three years of my life, I empathize deeply with the present-day discussions that revolve around whether it is necessary to read political theory if one has lived political experiences.

Hooks’ dedication to making feminism accessible to the general population is actually one of the major reasons “Feminism Is For Everybody” was and continues to be so compelling to me. It’s in this chapter that hooks also pinpoints, “by failing to create a mass-based educational movement to teach everyone about feminism, we allow mainstream patriarchal mass media to remain the primary place where folks learn about feminism, and most of what they learn is negative.”

This, in essence, is why I so passionately recommend this reading to fellow feminists. While I am the first to agree that lived experience can be inherently radicalizing, lived experience may fail to provide the detailed plans of action that political writings, like those of bell hooks, outline for us. “Feminism Is For Everybody: Passionate Politics” not only delves into the ways in which truly progressive political feminism can only ever be intersectional and accessible but simultaneously offers invaluable historical contextualization for how the contemporary feminist political movement grew and changed over time in the US. Knowing the history of the movement we wish to progress during our lifetimes is critical when our political opponents are currently abusing the same sexist rhetoric that has been weaponized in the past.